The War Inside 7-Eleven

7-Eleven recently sued the national franchisee association to block the use of its trademarks and now they’re being raided.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The sun hadn’t yet risen over Gurtar Sandhu’s 7-Eleven store near downtown Los Angeles on Jan. 10 when four plainclothes U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents swarmed inside. The place was busy; a lot of Sandhu’s customers are day laborers and other working people who start early. As dozens of customers poured themselves coffee and lined up to pay for morning snacks, the agents flashed badges and told employees to stay put. Three other agents, wearing dark ICE jackets, guarded the entrance, blocking anyone from coming in. The tension was heightened when one cashier darted out the back door into the dawn.

The night manager, Billy Davenport, watched from near the coffee urns. One of the agents handed him paperwork giving Sandhu 72 hours to produce records about every person who’d worked there in the past three years. Then the agents fired questions at Davenport and the other four employees left in the store: Do you have identification? Where were you born? How long have you been in America?

As the raid unfolded, Sandhu was on his way to another of his three 7-Elevens, in the nearby city of Carson. The 48-year-old father of three had built a life around 7-Eleven Inc., a retailer with almost 9,000 stores in the U.S., most of them operated by independent franchise owners. His own father had done the same: After fleeing violent ethnic conflict in northern India, he brought his family to the U.S. and found work behind a 7-Eleven counter. Years later, Sandhu and his dad bought their own franchise, then another, then two more. (They sold one in 2016.)

Sandhu was at the Carson store doing paperwork when the phone rang. Davenport was on the line. “They did what?” Sandhu responded. A few days later, two of the federal agents returned and Sandhu handed over a thick file of employee records, mostly copies of federal immigration forms called I-9s.

In August, sitting in the office of the store that was raided surrounded by boxes of Slurpee syrup, he said he didn’t know if or when he’d hear from immigration again. He appeared still to be baffled by his first experience with ICE. “I totally understand if you are doing something illegal,” he said, “I mean, if they know that I am doing something wrong. But why not just send me the subpoena and say we need to give them the information? Why all the drama? Why all the show?”

The show wasn’t just for Sandhu. The day he was raided, immigration officers fanned out across America, serving inspection notices and arresting suspected undocumented workers at 98 7-Eleven stores in 17 states and Washington, D.C. Since then agents have raided several more, and Bloomberg has learned that ICE and federal prosecutors in Brooklyn, N.Y., are engaged in criminal investigations of multiple franchises. 7-Eleven, an American icon and the world’s largest convenience store chain, has become the highest-profile target of a sweeping corporate immigration crackdown by President Trump.

It’s a huge headache and a public-relations nightmare for the company and its chief executive officer, Joe DePinto. But the immigration crackdown has also given 7-Eleven something potentially useful: the names of franchisees who might be in legal jeopardy. Store owners found in violation of immigration law could be in breach of their franchise agreements. And as they well know, 7-Eleven has the contractual right to take back a store from someone who’s violated his or her agreement. Which is why Sandhu’s mind went into overdrive when, on July 30, he received a letter from 7-Eleven demanding any documents alleging violations of immigration law and warning him that he risked having his store seized if he didn’t comply.

All’s fair in the bitter, protracted war between 7-Eleven and its franchisees. The tensions have built steadily in the years since DePinto, a West Point-educated veteran, took charge and began demanding more of franchisees—more inventory, more money, more adherence in matters large and small. Some franchisees have responded by organizing and complaining and sometimes suing.

As detailed in a series of lawsuits and court cases, the company has plotted for much of DePinto’s tenure to purge certain underperformers and troublemakers. It’s targeted store owners and spent millions on an investigative force to go after them. The corporate investigators have used tactics including tailing franchisees in unmarked vehicles, planting hidden cameras and listening devices, and deploying a surveillance van disguised as a plumber’s truck. The company has also given the names of franchisees to the government, which in some cases has led immigration authorities to inspect their stores, according to three officials with Homeland Security Investigations, which like ICE is under the jurisdiction of the Department of Homeland Security.

7-Eleven says it had no advance warning of the January raids, or any raids, and gives the government information about a franchisee only if it has reason to believe crimes are occurring inside a store. Still, franchisees, after years of conflict with the company, went from suspicious to paranoid when word spread that ICE had shown up at stores run by men and women who were in legal disputes with 7-Eleven or were prominent critics of DePinto. Bloomberg has documented raids on four such people, including Sandhu, who’s been involved in two lawsuits against the company. That’s why he can’t stop wondering: Why him? Of hundreds of 7-Eleven stores in Los Angeles County alone, why his?

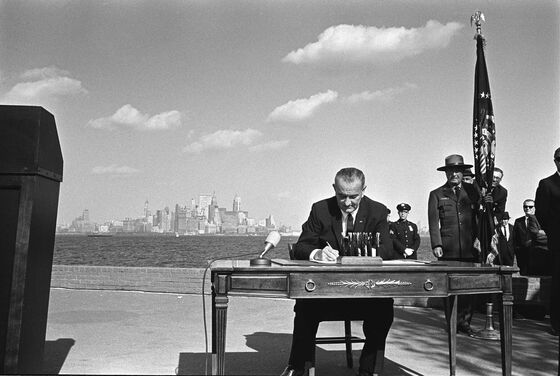

Tropes about 7-Eleven stores being owned by immigrants are largely on the money. The company, started in 1927 by a Dallas icehouse operator named Joe Thompson, began selling franchises in the 1960s to hasten growth. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act, which made it a priority to reunite immigrants with their families. Waves of people from India, Pakistan, and other Asian countries came to the U.S., and they were drawn to 7-Eleven. “I started talking to franchisees and asking them, ‘How did you end up here?’ ” recalls James Keyes, who had a 20-year run at the company and was CEO from 2000 to 2005. “Most said they came to the U.S. with nothing in their pocket and their first job was at 7-Eleven. They’d save enough money, make a down payment, and get their own store. Then they’d wire money back to relatives and say, ‘Come over here, and I’ll hire you.’ This replication kept happening throughout the ’70s and ’80s and ’90s, until all of a sudden it was a majority minority. It’s a beautiful story of the American dream.”

By the 1980s, so many immigrants were running 7-Elevens that the company and the convenience store industry it created became the butt of comedians’ jokes. Keyes says when he was introduced at an awards ceremony in the early 2000s, the emcee quipped, “Amazing, you’re the first 7-Eleven guy I’ve ever met who speaks English.” He didn’t laugh. Keyes went out of his way to laud the company’s diversity. When people were throwing bricks through the windows of 7-Elevens after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, he aired commercials that celebrated immigrant store owners. In 2002 he staged the company’s 75th anniversary party on Ellis Island.

Three years later, in 2005, Japanese billionaire Masatoshi Ito, who already owned a large stake in 7-Eleven, paid $1 billion for the remaining shares. This quintessentially American company became a subsidiary of a new Japanese holding company called Seven & I Holdings Co., which now has 67,000 convenience stores worldwide. Just days after the sale, Keyes retired and 7-Eleven brought in DePinto.

By then, store margins were thinning in the face of rising minimum wages, increasing costs, and heavier taxes on cigarettes and beer. When the global recession hit in 2008, the company’s Japanese owners prescribed an aggressive expansion strategy. Some owners felt betrayed when new stores were allowed to open near their own. DePinto also introduced additional fees, controls, and demands. In 2012 he rolled out a camera system that allowed Dallas executives to peer into any store at any hour of the day. By that point he had lost the support of many franchisees.

Running a 7-Eleven is a complex, stressful endeavor. A generation ago it was easy enough to make a living selling little more than milk, cigarettes, and lottery tickets. Today, according to franchisees, the company expects stores to keep an inventory of thousands of items at all times. Corporate employees or contractors, some disguised as mystery shoppers, regularly drop by stores to see if they’re abiding by a litany of rules, down to making sure the Red Bull cans are displayed front-facing. A range of infractions—from lesser things such as running out of Butterfingers and Diet Coke to more serious matters like failing to deposit the day’s receipts—can trigger warnings called letters of notification, which can lead to what 7-Eleven calls a breach of the franchise agreement. An accumulation of four breaches in two years can give the company cause to terminate an agreement and take over the store.

Not all of DePinto’s changes have been received poorly. Franchisees liked the introduction of 7-Eleven’s own Sonoma Crest Cellars wine brand to draw in more upscale patrons and an energy drink called Inked to target millennials. But they complain that other changes are expensive and burdensome, such as a requirement to stock fresh food, which means staffing additional people to prepare it. Then there are equipment costs—maintenance for the Slurpee machine alone is about $4,000 a year. Profits on store merchandise are the lowest they’ve been in a decade, according to company financial filings.

The company’s 2017 disclosure documents give the example of a store in Chicago with $1 million in annual sales. After all the fees and costs and taking into account that the company’s share of the take rises as revenue increases, the franchise owner took home $37,000 before taxes. “7-Eleven always sold its franchises as a gold mine,” says Hashim Syed, a former 7-Eleven franchisee and ex-president of the Chicago franchisee-owners association. “I say it’s more like a coal mine.”

The Farrukh Baig scandal changed 7-Eleven. Baig came to the U.S. in the 1980s from Pakistan and started at the bottom at one store. He was ambitious and soon bought his first franchise. Over the next 20 years he, along with his wife and several business partners, built a small empire of 14 stores in New York and Virginia. He was such a successful and well-regarded owner that the company picked him to serve on a franchisee leadership committee that provided input on 7-Eleven strategy. The company even distributed a recruitment flyer featuring Baig’s picture.

Then in 2010, a New York state trooper told immigration agents he’d received a tip about widespread hiring of undocumented workers and labor abuses inside Baig’s stores. The feds started digging and before long had cultivated a network of informants. The government later alleged that Baig was not only hiring undocumented workers but also outfitting them with stolen identities, stealing their earnings, and forcing them to work more than 100 hours a week while docking their pay for rent in housing that he owned.

As investigators familiarized themselves with 7-Eleven, they found it hard to believe the company’s executives knew nothing about what Baig was doing, according to six current and former federal law enforcement officials familiar with the case. The company is deeply involved in the minutiae of the stores—it regulates thermostats, tracks every sale with data analytics, and records every human interaction. Store owners are required to deposit all sales receipts into a 7-Eleven bank account. The corporate payroll department in Dallas reviews time sheets for each employee, deducts taxes, and sends workers their pay, sometimes on debit cards that don’t require a bank account. Franchisees’ earnings are deposited in their personal bank accounts.

In July 2011 the company received subpoenas demanding information about Baig’s stores. 7-Eleven vowed to cooperate with the investigation and over several months handed the government copious amounts of information, including payroll records for every store in the U.S. It’s possible those records are still being mined by immigration officials for leads on stores to raid, according to a person familiar with the company’s operations.

DePinto and other 7-Eleven executives told investigators on multiple occasions that they were shocked to learn about Baig’s alleged behavior and urged the government to prosecute him aggressively, the law enforcement officials say. Nonetheless, by May 2013, prosecutors told the company they were opening a new front in its investigation. They began probing the operations of the Dallas headquarters for potential violations of immigration and payroll laws.

The bust of Baig was on June 17, 2013. Then came a shock. In September, three months after Baig and eight others were indicted—and now several years into the government’s case—investigators received a call from an attorney at Jones Day, the company’s outside counsel, requesting a meeting. At a sitdown at the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Brooklyn, 7-Eleven’s lawyers revealed that the company had investigated Baig eight years earlier. An anonymous handwritten letter had come into corporate headquarters, detailing labor abuses and the hiring of undocumented immigrants at Baig’s stores. 7-Eleven had conducted an investigation and presented findings to the company’s audit committee. Now the lawyers were disclosing that report. It cleared Baig of any wrongdoing. The anonymous nature of the letter impeded 7-Eleven’s ability to investigate the claims, Stephanie Shaw, a spokeswoman for the company, said in a statement.

The prosecutors and investigators on the case were incensed. The revelation caused the government to intensify its probe, which at one point involved pressing 7-Eleven to pay a substantial fine and consent to government oversight. “We wanted to make sure the control environment was such that it wouldn’t allow for franchisees to ever do this again,” says a former senior law enforcement official involved in the discussions. The company pushed back, arguing it couldn’t be held liable for the behavior of independent operators. Ultimately, the government didn’t prosecute or penalize the company or its employees. In 2015, Baig was sentenced to more than seven years in federal prison. The following year, the U.S. Attorney’s Office informed 7-Eleven that it was no longer considering a case against the company.

Around the time the government started investigating Baig, DePinto began building a group of ex-cops and private eyes charged with identifying stores that were cooking the books, skimming cash, or otherwise gaming the system. One goal was to build cases to terminate franchise agreements, according to former employees interviewed by Bloomberg and lawsuits filed across the U.S. The tactics could be aggressive. In a 2014 lawsuit, Adnan Khan, a leader of 7-Eleven franchisees in California, alleged that a company investigator followed him for months in an unmarked car and at one point hit and injured him with the vehicle. 7-Eleven settled the suit.

In the corporate office and inside stores there was talk about lists of franchises targeted for repossession, known internally by code names including Operation Philadelphia and Operation Take Back. Multiple lawsuits have alleged that stores on the list were owned by members of 7-Eleven franchise owners’ associations. For years, they’d agitated against DePinto’s policies.

Executives tried to keep the programs secret but were forced to reveal their existence during discovery as multiple lawsuits proceeded through the judicial system. In December 2015 a federal magistrate admonished 7-Eleven for trying to conceal the programs in defiance of multiple court orders, saying that “the court was thoroughly frustrated by 7-Eleven’s obfuscation.”

Shaw, the company spokeswoman, characterizes the programs as “short-lived initiatives to curb fraud in a small number of stores in New Jersey and Philadelphia.” Greg Franks, a senior vice president who was involved with Operation Philadelphia, says 7-Eleven employs extreme measures such as surveillance only in “rare cases,” including fraud or other conduct potentially damaging to the 7-Eleven brand. “Termination is a costly, tiresome, never-ending legal process,” he says. “Nobody wins in a termination.” The company says 2.4 percent of stores changed ownership last year, and of those “only a tiny fraction” were involuntary terminations.

Earlier this year company investigators scoured store surveillance cameras to gather evidence that immigration agents had raided stores in Chicago on April 12, according to internal documents reviewed by Bloomberg. Last summer, 7-Eleven cited evidence of immigration raids to go after Ketan Patel, president of the Chicago franchise owners’ association, who’d organized opposition to the company’s most controversial policies. ICE visited four of his eight Chicago-area stores on April 12 and arrested four employees. On Aug. 1, 7-Eleven filed a lawsuit citing those events and alleging that Patel had underpaid workers and failed to comply with immigration laws. Two days later, the company seized all of his stores. Patel, who declined to comment for this story, said in court documents that he did not underpay employees and that he took reasonable steps to verify his employees’ legal status.

Donna Bucella, a former federal prosecutor who was hired in January as chief compliance officer at 7-Eleven, says the company doesn’t steer investigators toward store owners with whom it has disagreements or disputes. If the company has specific, credible evidence of wrongdoing, she says, it will pass it along to law enforcement. Bucella says she didn’t know about the company reviewing store tapes.

Paranoia has swept across the universe of 7-Eleven franchisees. At franchisee conventions, inside stores, and on private email chains, they swap stories about perceived offenses from headquarters in Dallas. In particular they’re alarmed by the ICE raids on stores owned by critics of the company. They all but assume 7-Eleven has something to do with it.

That was the first thing Sandhu thought when he heard about the raid on his store. Within hours, friends began stoking his suspicions, asking, “What did you do to upset 7-Eleven’s executives this time?” Sandhu knew why they were asking. In 2014 he and four other Los Angeles franchisees sued the company, accusing it of deploying threats, intimidation, and trumped-up allegations of wrongdoing. Last year he was a material witness in another lawsuit, which claimed the company was treating franchisees as low-wage employees, not as independent store operators, and as such was violating state and federal labor laws by failing to pay overtime. 7-Eleven denied the allegations in both suits, and they were dismissed. The franchisees are appealing the overtime wage case.

7-Eleven has recently taken steps to ensure stores don’t hire undocumented workers. It’s introduced a contract that will require stores to certify compliance with U.S. immigration law. The company also plans to outsource payroll services. The new franchise agreement also piles on additional costs, according to an analysis by the national franchise owners association. That includes an $8,000 grand-opening fee for some stores and a $50,000 renewal fee. And it gives a bigger share of gross profits—up to 59 percent—to 7-Eleven. Franks says more than 80 percent of franchisees eligible for renewal have said they plan to sign the new agreement.

All this has escalated the feud between the company and its franchisees. 7-Eleven recently sued the national franchisee association to block the use of its trademarks. The association and its members boycotted the company’s annual meeting in Las Vegas in February, despite 7-Eleven’s attempt to lure them with entertainment featuring A.R. Rahman, a Bollywood legend. Five months later, DePinto wasn’t invited to speak to the franchisees’ own annual meeting outside Orlando.

Anger was palpable at the franchisee meeting when Allison Carter Anderson, a special agent with the Department of Homeland Security, stood onstage in a ballroom before hundreds of 7-Eleven store owners. Most were immigrants from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and China, and many were terrified of the prospect of people like Carter Anderson showing up at their doors. But they’d invited her here, out of desperation and in search of answers, to explain how to comply with federal immigration law. She handled the crowd well, plodding through a PowerPoint deck for a government program called Image, which gives businesses a chance to open their payroll records voluntarily in exchange for getting lenient treatment if any violations are discovered.

When Carter Anderson paused and asked if anyone had questions, Serge Haitayan took a microphone. He owns a 7-Eleven on a highway lined by grape farms in Fresno, Calif. Last year he joined Sandhu in the lawsuit alleging 7-Eleven was wrongly treating them like employees. On July 16 of this year, three federal agents walked into the little store he’s operated for 28 years, giving him three days to produce employee records dating back a year. He did that, and he hasn’t heard from ICE since.

“Why is immigration targeting 7-Eleven?” Haitayan asked Carter Anderson, drawing a rumbling of support. “Why?”

Carter Anderson paused, smiling nervously, as she scanned the crowd. “I understand getting this question,” she said. “But I cannot specifically answer this question.”

Haitayan continued. “All I hear is 7-Eleven being raided. It seems to be we are the only ones being targeted by ICE. Why?”

“I’m sorry,” she said.

The audience boiled over. One man shouted from the back: “So are you saying you can’t answer our questions? I don’t see why you are dancing around this question!”

Perhaps some of the franchisees would have liked DePinto to be there. But he had other business that day. He spent it making inspections of stores while some of their owners were away at the annual meeting.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Ferrara at dferrara5@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.