America’s Favorite Truck Is About to Test Tesla’s Dominance

America’s Favorite Truck Is About to Test Tesla’s Dominance

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Ford began developing an electric version of its wildly popular F-150 pickup four years ago, many people doubted it could be as robust as the gas-powered brute. Some of them were inside the house. “We were dealing with a ton of skepticism internally,” says Linda Zhang, chief engineer on the project. “It couldn’t just be a battery on wheels. We wanted it to be a real American truck that does work.”

It also needed to add value, using electric power to do things a regular truck couldn’t. So Zhang asked her engineers to come up with features “that hadn’t been invented yet.” Some of the ideas they ran by consumer focus groups worked, like a truck-bed scale connected to a dashboard readout and to an LED taillight display showing available capacity. Others didn’t, like a “bed extender” that used a small elevator to lengthen the truck at the back. “People said, ‘I would just buy a longer truck if I needed that,’ ” Zhang says.

What wowed the consumers participating in Ford Motor Co.’s clinics was the engineers’ spin on an EV standby: the frunk. Already popularized by Tesla Inc. and featured in Ford’s Mustang Mach-E, the front trunk offers storage under the hood, where the internal combustion engine would otherwise be. But the Lightning engineers went Texas with the concept. Their “Mega Power Frunk” had 14 cubic feet of space capable of holding 400 pounds of cargo, plus a deep well with a drain for iced beverages—ready for “front-gating,” as Ford calls it. (“Frail-gating” apparently didn’t make the grade.) “You can have a party on both ends,” says Suzy Deering, Ford’s head of marketing.

The engineers also wired the frunk so that, at the touch of a key-fob button, it opened wide like the jaws of an amusement park dragon. That—and the fact that the frunk can fit two sets of golf clubs—got one clinic participant so excited, he stood up on his chair. “He was a big, hairy guy with a big beard, who I would not have written down as a golfer,” says Darren Palmer, vice president for Ford’s global EV programs. “But he’s a business owner who drives a top-end Platinum truck.” The man told everyone, “When I pull up to the country club and push the button and that thing opens electrically, everybody is going to gather around me, saying ‘What the hell?’ ”

Ford’s decision to fully electrify America’s bestselling vehicle of the past 40 years wasn’t made lightly. In good years, the company sells close to 900,000 F-Series trucks, generating more than $40 billion in annual revenue. If the F-Series were a company, it would bring in more money than Coke, McDonald’s, Nike, or Starbucks. It’s also been a technology showcase for Ford, becoming the first pickup outfitted in lightweight aluminum body panels to improve fuel economy.

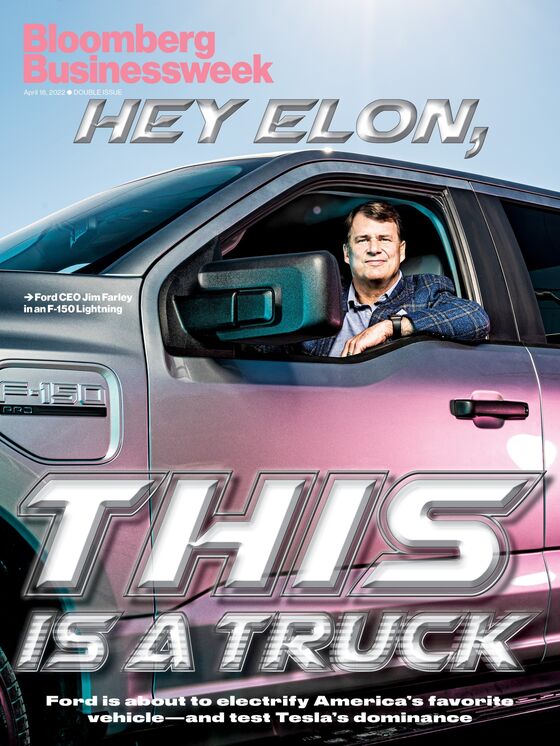

But the company followed suit when legacy automakers began converting to plug-in models to meet stringent global mandates for zero-emission vehicles and respond to the growing competitive threat from Tesla. In 2019, Ford announced it was working on a fully electric F-150. Since becoming chief executive officer almost 19 months ago, Jim Farley has boosted the company’s spending on EVs from $11.5 billion to $50 billion, and in March he cleaved its carmaking operations in two, creating a “Model e” unit to scale up EVs and “Ford Blue” to focus on traditional internal combustion vehicles. He estimates that battery-powered vehicles will account for as much as half of Ford’s global sales by 2030, and the hope is that eventually its entire fleet will be electric.

Farley sees the Lightning as a bet-the-company proposition—Ford’s biggest move since Henry ditched the aging Model T to make way for something new. “Does it keep us up at night? You betcha,” Farley says. “It’s America’s most popular vehicle, and there is no more trusted brand in our industry. It feels a lot like the Model A launch in 1928.”

The electric F-150 is thus both an existential imperative and a massive opportunity to repeat a category-defining hit. And whether Ford succeeds isn’t important merely for the company. Only about 3% of U.S. auto sales were electric last year, while Europe approached 20% and China accounts for more than half of all EVs sold worldwide. “This vehicle is a test for adoption of electric vehicles,” Farley declared when the truck was unveiled in a nighttime ceremony at the company’s Dearborn, Mich., headquarters last May. “We should all watch very carefully how this does.”

That’s where the frunk comes in. Ford has been aware from the outset that for the Lightning to become a smash, it needs to appeal both to buyers who are already in on the $27 billion electric vehicle market and to those who are in the $124 billion pickup market. That process began with the engineering and will extend through to how the truck is marketed.

The Lightning goes on sale in late April, with a price starting just under $40,000, and so far, things are trending extremely well. Ford was overwhelmed with nearly 200,000 reservations, leading it to almost quadruple capacity at the truck’s new factory, from 40,000 vehicles annually to 150,000. The Lightning’s glow helped boost Ford’s stock price more than any other automaker’s last year, and in January the company briefly topped $100 billion in market value for the first time.

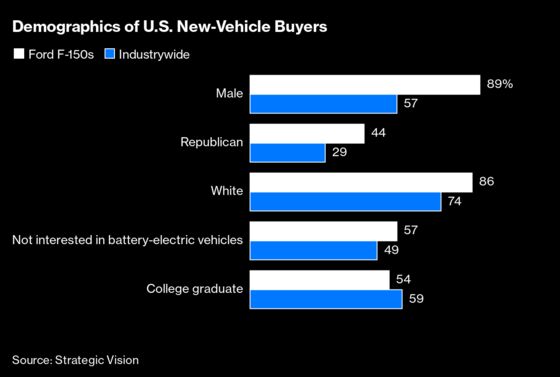

Most of those queuing up for the Lightning aren’t truck traditionalists, though. Instead, the company says, they’re buyers who are new to pickups or new to Ford—early adopters who’d normally deny American automakers not named Tesla a second look. And while that’s a feat for the 118-year-old company, winning over the old guard will be tougher. According to the latest survey of 250,000 new-vehicle owners by Strategic Vision, a research firm, nearly 9 out of 10 F-150 buyers are White males, with a median age of 57. Almost 60% say they’re not interested in an electric vehicle.

Ford still has its gas-powered F-series trucks, which start at $30,000 and sell for about $63,000 on average, to appeal to these folks. It expects to continue selling hundreds of thousands a year for many years. But Ford will have to be in compliance with those regulations targeting conventional vehicles eventually. And for its big investment to pay off, it will need the fossil-fueled crowd to buy in, too.

In reimagining the F-150, Ford had some basic economic and industrial realities to consider. Behind the spectacular sales figures are three U.S. factories that each make a truck per minute, on average. The F-Series supports the jobs of a half-million Americans and contributes $49 billion to the U.S. gross domestic product, according to a study Ford commissioned from Boston Consulting Group. There are about 17 million of the pickups on American roads, accounting for roughly 6% of all vehicles in operation. The only U.S. product that generates more sales revenue is the iPhone.

The strength of the line argued for a gradual approach to electrification. Essentially, the company retrofitted an existing F-150 with an electric powertrain rather than develop an entirely new truck. It’s reusing about 50% of the current pickup, which already offers a gas-electric hybrid powertrain option. Virtually the entire passenger cab is the same, save for the 15.5-inch touchscreen lifted from the dash of its hot-selling electric Mustang Mach-E. Ford also barely changed the Lightning’s look, adding only an extra light bar over the headlamps to distinguish it from the conventional truck. “Why do I need to invent all-new seats and door handles?” asks Ted Cannis, who worked on early development of the Lightning and now runs Ford’s commercial business.

Farley acknowledges there are risks to an incremental approach in a market that has tended to reward innovation. But he sees the payoff in being first to sell a traditional electric truck, long before Ford’s chief competitors in the segment, and at a price competitive with both gas-powered options and the few electric models available or coming soon. “We could have gone more radical with the design,” he says. “But when we did the hard, cold math years ago, we came to the conclusion that we could offer our customers an electric vehicle at almost the same price as an ICE [internal combustion engine] vehicle.”

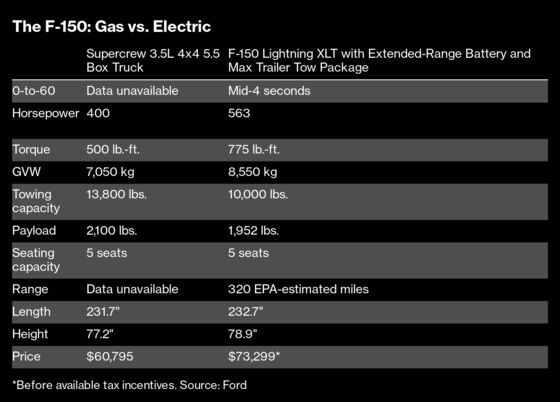

When the Lightning goes on sale, it will face a couple of thus far low-volume competitors: Rivian’s smaller R1T pickup, which starts at almost $80,000, and General Motors Co.’s GMC Hummer, the first editions of which cost $112,595. Tesla has pushed back the Cybertruck’s launch until at least 2023. And an electric version of the F-150’s key competitor, the Chevrolet Silverado, won’t get to market until next spring. The arrival date of the electric Ram pickup is uncertain.

A lot of the Lightning’s development work focused on performance—on proving to consumers that the truck could match or exceed the gas-powered line on the kinds of metrics that traditionally get buyers excited. “In the early days, every time we spoke to somebody about the truck, they would always ask, ‘But can it tow?’ ” Palmer says. “I finally said, ‘I’m sick of all these questions about towing, just sick of it. Instead of just telling everyone, “Trust us,” let’s prove it.’ ”

Ford’s first big public pitch for the electric F-150 became a publicity stunt that Zhang refers to as “our little train tow.” In July 2019, with cameras rolling, she drove a battery-powered F-150 in a train yard while pulling 10 double-decker rail cars filled with 42 gas-engine F-150s—a total weight of 1.25 million pounds. The prototype only dragged the load for 1,000 feet, and Ford cautioned that it was far beyond a production pickup’s recommended capacity, but the point was made. The video went viral, drawing 2.5 million views on YouTube.

The production truck eventually settled in at a 10,000-pound towing capacity, more than most conventional versions. Its 563 horsepower and 775 pound-feet of torque make it Ford’s most powerful F-150 ever. And it can go from zero to 60 mph in 4.3 seconds—sports-car speed. The base model runs 230 miles on a charge, while an optional extended-range battery expands that to 320 miles.

The engineering process also led to some new features that gas vehicles couldn’t begin to compete with. The frunk, obviously, but also portable electricity generation. The value of this capability entered the national conversation when a 100-year ice storm hit Texas early last year, leading an owner of Ford’s gas-electric hybrid F-150 to use its truck-bed outlets to temporarily keep the lights on and the music playing at home. Ford’s publicity machine kicked in and placed stories on network and cable news about hybrid F-150s saving the day.

Ryan O’Gorman, the Ford engineer leading the development of the Lightning’s portable power feature, immediately saw the potential. The hybrid F-150 wasn’t capable of powering an entire house, but the Lightning’s system was far more sophisticated. By design, it connects to a home charger that’s typically set up in a garage. If a blackout occurs while the Lightning is plugged in, the truck’s battery silently kicks in to power the entire house, for days if need be—something a Tesla can’t do. The only thing an owner would notice would be an alert from Ford’s smartphone app.

O’Gorman happened to be visiting his parents in Houston when Texas froze over. “I can’t tell you how many calls I made back to Detroit to say this would have been such a game changer” if the Lightning had already been on sale, he says. It was too late for that, but it wasn’t too late to start selling the feature to buyers. Within a few months, Ford rolled out an ad with the craggy voice of actor Bryan Cranston promising that the company would “take the truck our parents used to build this country and make it so it can power our homes.”

A bigger PR bonanza still came in May 2021, after President Joe Biden delivered a speech at the new Lightning factory in Dearborn. When he finished, he hopped in the driver’s seat of a prototype, and Zhang—a Chinese immigrant whose first ride in a car came when she arrived in America as an 8-year-old—gave him a quick tour. Then Farley offered the president a piece of advice: “Mash the throttle.” Biden did, rocketing across the tarmac before rolling to a stop before the press corps. “This sucker’s quick,” he said.

Clips of the test drive circulated widely, a major signal boost for Ford’s announcement the next day that buyers could start reserving their trucks. But the Biden bump also pointed to the conundrum the company was facing. In appealing to the sorts of people who like the president, could the Lightning still reach the ones who might not?

Matt Meredith has six Fords in his driveway and four tattooed on his body. At 31, he’s a third-generation Ford man, and his fleet includes three F-150 pickups. He wouldn’t consider driving anything else. But his affinity has limits. “I really have no desire to get a Lightning,” he says. As the owner of Bullseye Custom Autos in Austin, he considers the truck’s range when towing a sizable load a major concern. By his calculations, a Lightning would have to stop nine times to recharge when he pulls the vehicles he soups up to the annual custom car show in Las Vegas. “That’s a deal-breaker,” he says.

The role the truck could play in combating climate change isn’t a consideration. “I just don’t think electric vehicles are necessary for the world or for clean air,” Meredith says. “I couldn’t care less because what the traffic produces in America as far as output for ozone and greenhouse gases doesn’t compare to what factories produce.” (The International Energy Agency estimates that carbon dioxide emissions from transportation in the U.S. exceed those from industry by 4 to 1.) He describes his politics as libertarian, leaning Republican, and says he sees the government’s EV push as purely political. “Ultimately,” Meredith says, “it’s a way to control a population.”

Winning over the die-hards could be the marketing challenge of the century. Rick Ricart, a Ford dealer in Ohio, says that group views battery-powered trucks as “strange alien spacecraft.” To reach many of them, Ford will have to overcome some deeply embedded (and often highly gendered) stereotypes about electric vehicles, as well as some entrenched political divisions.

Early in the Lightning’s development process, the company conducted one of its customer clinics in the heart of truck country—Texas, which accounts for about 1 in 5 U.S. truck sales. A roomful of F-150 owners were asked, “If an electric vehicle were a dog, which breed would it be?”

“This huge, burly Texan scoffs and says, ‘It would be one of those little Chihuahuas,’ ” Palmer recalls. “Then we said, ‘OK, what kind of drink would it be?’ And he scoffs again and says, ‘Pink Champagne.’ ”

Dan Albert, an automotive historian and the author of Are We There Yet? The American Automobile, Past, Present, and Driverless, says such attitudes follow from a long tradition. “The EV was always marketed as the lady’s car, from the very beginning,” he says, “all the way up until Tesla,” which managed broader appeal by emphasizing cutting-edge technology and sports-car-like styling and performance. At its extreme, the perception has played out in a form of bullying—think of rolling coal, in which pickup owners who’ve modified their vehicles with upright exhaust pipes belch black smoke at EVs or hybrids and obscure their view. “It’s part of the culture wars,” Albert says. “You saw it in the Black Lives Matter protests, when there was coal-rolling trucks running through the crowds.”

The most extreme anti-environmentalists will never be converted, he says. That’s fine for Ford in the short run. More than fine, even. Having everyone switch quickly would be bad for business. The company’s century-old drivetrain has much fatter margins than high-cost ion power, and it generates most of Ford’s profit. That’s the great irony of Farley’s big bet on electric: He still needs hundreds of thousands of people to buy a conventional F-Series truck each year to finance the company’s electric future. “We have people in rural America, we have people who are doing jobs in the energy sector on the north slope of Alaska,” Farley says. “For so many of them, it still won’t make sense for many years.” The company’s target is for electric versions to account for 30% to 40% of annual F-150 sales by the end of the decade.

Deering, Ford’s marketing chief, is preparing an ad campaign targeted at traditionalists. Referred to internally as “the Bold Guardians,” it aims to sell them on the truck’s strength, acceleration, speed, and new features, while downplaying fears about running out of juice. “We feel very responsible to help break down the myths,” Deering says, referring to ads that “escort our current customer into the electric revolution.”

Ultimately, Farley maintains, what’s really necessary to win over Ford’s owner base is the kind of seat time in the Lightning that the president got. “Once our core customer gets behind the wheel, like Joe Biden did, and mashes the throttle pedal, they will instantly understand how a heavy F-150 full-size pickup truck goes zero to 60 in 4.3 seconds,” Farley says. “It will have the neighbor-wow factor that we need to be a breakthrough product.” —With Craig Trudell

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.