The Great Antitrust Awakening Can’t Be Stopped

The Great Antitrust Awakening Can’t Be Stopped

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Two decades ago the U.S. government tried to break up Microsoft Corp. It accused the company of leveraging its operating-system monopoly to squash the rival Netscape browser. An epic, yearlong trial ended in the summer of 2000 when a federal judge found Microsoft guilty of antitrust violations and ordered it split in two.

For a brief moment, it appeared that tough antitrust enforcement—largely dormant since the government abandoned its 13-year quest to break up IBM Corp. in 1982—was resurgent. But it wasn’t to be. The breakup order was reversed on appeal, and the Microsoft case was quickly settled once George W. Bush became president.

After which, well, let’s see: There have been six airline mergers since 2000, reducing the number of major carriers from 10 to 4. There have been 42 pharmaceutical mergers worth more than $10 billion each. So many financial institutions have combined that there are only four national consumer banks left: JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo. Thanks to consolidation, just four companies control 76% of the nation’s soybean market. Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google, meanwhile, have grown into enormously powerful companies that are often accused of crushing rivals and squelching innovation.

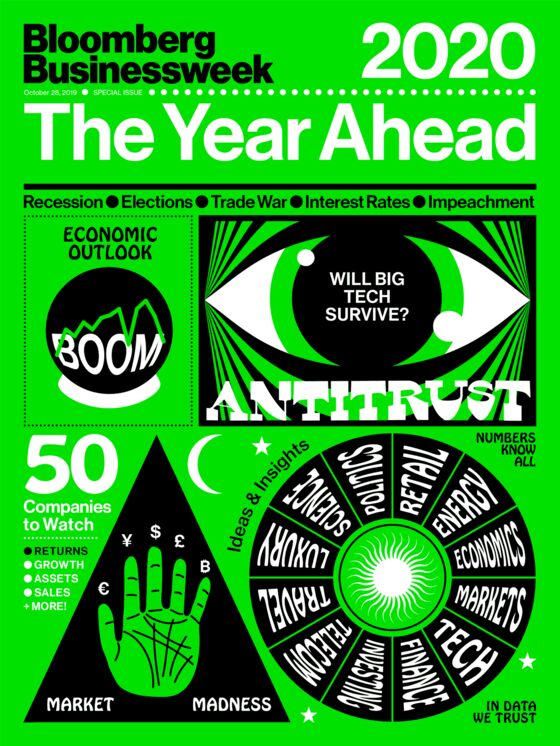

And people have noticed—people like Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren, who’s called for the big tech companies to be broken up; Representative David Cicilline, the chairman of the House antitrust subcommittee, who’s holding hearings to determine whether new antitrust laws are needed; and Chris Hughes, a Facebook Inc. co-founder who now believes the social media giant has too much power. Hughes is launching a $10 million fund to raise public awareness about monopolies. Donors include another tech pioneer, Pierre Omidyar, who started EBay. Antitrust has become such a big deal that it seems certain to be a dominant theme in the presidential election—the last time that happened was 1912—making 2020 the year of the great antitrust reawakening.

Facebook and Google already face antitrust investigations from the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice. Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. are likely to be added to the list. All but two of the 50 state attorneys general are probing Google and 45 are looking at Facebook. It’s not just that people are calling for something to be done to reduce the power of the big tech companies. It’s that, for the first time since the late 1970s, a genuine rethinking of the way antitrust laws are enforced appears to be taking place.

For much of the last century, government regulators were inherently suspicious of dominant companies. That started to change in 1978, with the publication of an important book by Robert Bork, The Antitrust Paradox. Bork argued that what should really matter is not a company’s market share, but whether its actions harm consumers. In fairly short order, this so-called consumer-welfare standard became antitrust dogma, embraced by economists, regulators, and the courts. Louis Brandeis, the late Supreme Court justice and a chief advocate of breaking up big companies during the long-ago era of the “trustbusters,” must have rolled over in his grave.

The next rethinking began with the rise of the major tech companies. Critics complained that they ran roughshod over consumer privacy, used their platforms to favor their own products over rivals’, and squelched innovation by scooping up potential competitors. But because consumers paid nothing to use Facebook and Google, and Amazon largely pushed consumer prices lower, the companies were mostly immune to antitrust action because of the consumer-welfare standard. That didn’t seem right.

In early 2017 a Yale law student named Lina Khan made the case in the Yale Law Journal that Amazon has operated in deeply uncompetitive ways. The article galvanized academics and economists who’d begun thinking about how to rein in Big Tech. They became known as the neo-Brandeisians.

Then something else happened: People such as Barry Lynn with the think tank New America Foundation—people who’d been saying for years that the consolidation of American business was harming the country—began to finally get a hearing. The slow recovery from the financial crisis, income inequality, the inability of workers to get raises even in a full-employment economy—suddenly all these disparate things seemed related. What connected them, some academic research found, was the consolidation of one industry after another, waved through by antitrust enforcers, giving a small number of companies great power.

Cicilline is a good example of how the issue has evolved. The Rhode Island Democrat, a lawyer by training, hadn’t thought about antitrust since law school in the mid-1980s. But in 2014 he agreed to join the House antitrust panel as its ranking member. That got him looking closely at the power of “the platforms,” as he calls Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

As co-chair of the Democratic Policy and Communications Committee, he was charged with developing the House Democrats’ agenda. “It became clear to me that one of the central issues was the economic concentration of power,” he says, “that resulted in fewer choices, higher prices, and so on.” And that this concentration had taken place because there hadn’t been enough attention paid to antitrust policy.

Finally, the discovery that Cambridge Analytica had gained access to the supposedly private data of tens of millions of Facebook users, which it used to help the Trump campaign, turned Cicilline into a strong advocate for tougher antitrust enforcement. He’s holding hearings he expects will lead to a series of antitrust proposals that could make it easier to bring enforcement cases. Lina Khan is now counsel to his antitrust subcommittee.

Much of Washington has had a similar awakening. Warren, for instance, believes that “today’s big tech companies have too much power”—which is why she is proposing to break them up. Senator Cory Booker, also running for the Democratic presidential nomination, wants to halt agriculture mergers because of all the consolidation that’s taken place in that industry. At least a half-dozen other presidential candidates are calling for investigations into Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

It’s not just Democrats, either. Josh Hawley, Missouri’s new Republican senator, is a harsh critic of the tech companies. Other Republicans complain that Facebook and Google, in particular, are biased against conservative viewpoints and want to reduce their power over public discourse.

Then there’s the president, who loves to take potshots at Amazon, possibly because its chief executive officer, Jeff Bezos, owns the Washington Post, which Trump considers biased. The president’s critics say he’s weaponizing antitrust for his own political purposes, confirming the degree to which antitrust policy is up for grabs.

There are, of course, plenty of people, mostly conservative economists and lawyers, who continue to believe the consumer-welfare standard is the right one and no change is needed. The courts, by and large, still adhere to that view. But consider again the Microsoft case. It’s true that the government failed to break it up, as it had hoped to do. Nonetheless, the trial made a huge difference: Microsoft became a much different company, gun-shy about using its market power to crush potential rivals.

It’s not too much to say that because of the government’s willingness to use the most extreme measure in the antitrust toolbox—going to court to break up Microsoft’s monopoly—new companies were able to flourish. Companies like, well, Amazon, Facebook, and Google. Will the current focus on antitrust do the same for the next generation of innovative companies? We can’t know the answer to that yet, but it’s the question everyone should ask.

A Guide to the Key Concepts and Terms in Antitrust Enforcement

Sherman Antitrust

Dating to 1890, this was the first federal law to prohibit monopolistic business practices, banning activities that restrict interstate commerce and competition in the marketplace. Section 2 makes it illegal to monopolize, attempt to monopolize, or conspire to monopolize, but doesn’t define what constitutes unlawful “monopolization.” Although it’s broad, over the years the law has been interpreted and narrowed by the courts.

FTC

The bipartisan independent federal agency was established in 1914 by the Federal Trade Commission Act. It was created to bolster antitrust enforcement and clarify the Sherman Act. The intent initially was for the agency to aid in preventing monopolies. Today it has a dual mission to promote competition and protect consumers by enforcing the FTC Act, the Clayton Act, and other consumer-protection statutes.

Consumer-Welfare Standard

A bedrock of modern antitrust law, made famous in a 1978 book by Robert Bork, the late Yale Law School professor and former solicitor general. It says just because a company is big doesn’t mean it’s bad. The test is whether consumers are harmed, such as by a company’s ability to maintain higher prices. Blind adherence to the standard, critics say, has led to giant companies wielding huge economic and political power, and to less innovation, fewer jobs, lower wages, and the disappearance of smaller competitors. The standard didn’t envision the problem of network effects.

Network Effects

Network effects are especially important in technology, where the value of a product increases dramatically the more people use it. Since the phenomenon was first explored in the late-1990s Microsoft antitrust case, network effects have gotten more pronounced online. Google’s internet browser and Facebook’s social media app have so many users that it’s almost pointless to compete with them. And their popularity helps the companies collect troves of consumer data, which can be used to boost all their businesses and deepen their advantages over potential rivals.

Tipping

A digital company whose innovations give it a competitive advantage can quickly become the dominant player in a market, a phenomenon called tipping. It happens especially when network effects are strong. When a market tips in favor of a company, rivals often find the leader so hard to dislodge that they don’t even try to develop competitive products.

Kill Zone

A frequent complaint is that the tech giants are able to snuff out potential rivals by buying them up and killing them off, or stifle innovation by copying competitors’ most interesting new features such that startups hesitate to think big. Does the kill zone really exist? Some economists say yes, as evidenced by the decline of venture capital going to industries dominated by Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Dimitra Kessenides at dkessenides1@bloomberg.net, Paula Dwyer

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.