That’s $15 an Hour? Nah, Per Day. And the U.S. Congress Is Fed Up

U.S. Congress and AMLO May Finally Force Labor Reform in Mexico

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Mrs. Martínez earns $79 for a six-day week working in the produce section of a Walmart in Mexico City. A labor union bargained with the retail giant to get her that salary, but she’s never met a representative. She didn’t want to be named for fear of reprisals, but she says she hasn’t even heard of the union.

“Bargaining” is a stretch to describe what the union actually did, which is more like rubber-stamping. The collective contract that covers Martínez’s store allows starting salaries around the minimum wage, which has fallen so far behind inflation that few in the capital actually work for it. Walmart Inc. pays dues on workers’ behalf.

That’s not how unions are meant to work. But in Mexico they do, and not by accident. Low pay has been central to the country’s economic strategy in the quarter-century since Nafta began, boosting its appeal as a cheap base for exports to the giant consumer market up north. Many businesses that took advantage of cheap Mexican labor were American, turning the wage gap into a bone of contention between the two countries. The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, negotiated last year to replace Nafta, has more worker protections. But U.S. lawmakers—particularly House Democrats—insist on proof that Mexico is finally serious about boosting wages and threaten to block ratification of the deal until they get it. Mexico’s new labor-friendly president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, says he wants an economy that’s more driven by domestic demand anyway, which puts the unions in a political vise.

U.S. efforts to ensure that more worker protections make it into the new deal have focused primarily on companies that sell goods to the U.S., including automakers, which have also been targeted by the Trump administration for suppressing wages. But American labor groups, who have been working with Democrats on details of the new trade accord, say the problem is wider. Nonexporters such as Wal-Mart de México, the nation’s biggest private employer, are a key part of it.

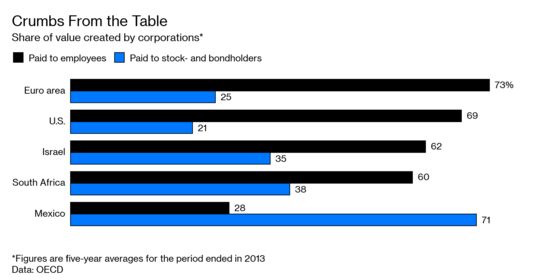

The deals unions make with employers are known as “protection contracts.” Companies say they need them because if they don’t have a contract in place, any union can go to the labor board and demand a work stoppage while it bargains with the company. Ben Davis, director of international affairs at the United Steelworkers, an AFL-CIO affiliate, interprets the term differently. What the contracts actually protect, he says, is “the ability to keep paying people 50¢ an hour.” An OECD study of some 30 countries found that Mexico had by far the smallest labor share—the chunk of economic output that goes to workers in the form of wages and salaries—while the profit share was the highest.

Joyce Sadka, a labor expert at Mexico City’s Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México who’s developed algorithms to analyze collective contracts, estimates that about three-quarters of those signed at the national level don’t grant workers anything beyond their basic legal rights. She says that when dues are transferred directly from companies to unions in exchange for contracts that offer little to workers, who don’t know they exist, the agreements often amount to “collusion deals between the company and the union.”

The leader of CTM, the union confederation responsible for Mrs. Martínez’s labor contract, argues that having businesses pay unions directly helps workers because the money doesn’t come out of their pockets. CTM’s labor contracts “are legally valid, and their periodical revisions are done according to the law,” wrote Senator Carlos Aceves, the group’s secretary general, in an emailed statement.

López Obrador, known as AMLO, was elected in a landslide last year promising a fairer distribution of income. After taking office in December, he raised the minimum wage from about $4.60 a day to about $5.40, still one of the lowest in the region. His government is racing to comply with the revamped Nafta labor rules so that the pact can get through the U.S. Congress before its summer recess. Democrats won’t be satisfied with changes on paper, even if they’re enacted by a labor-friendly Mexican leader. They’ll want follow-through, according to congressional aides, including financial resources made available for enforcement and evidence that the judicial system can address cases of unfair treatment.

New laws that will require each worker to vote on unions, union representation, and labor contracts were due in Mexico’s Senate in late April after passing the lower house earlier in the month. But López Obrador doesn’t control the local governments that approve many labor contracts, and local leaders are rushing to clinch state-level pacts with pro-business unions that could curb the right to strike.

Mexico Labor Minister Luisa Alcalde says strict timelines in the labor law, strong political will from the president, and a working group comprising her ministry, the Finance Ministry, and state governors, will ensure swift enforcement nationwide. The law “hits at the heart of the matter,” she says. “This is not just makeup.” Meanwhile, even as AMLO faces U.S. pressure not to drag his feet on pro-labor reforms, he’s also being warned not to move too fast. After decades of rule by business-friendly parties, there’s pent-up demand among Mexican workers, and the arrival of a more sympathetic president triggered a wave of stoppages.

Walmart is among the companies that have announced a wage increase since AMLO took office. In March it promised a 5.5 percent hike in average nationwide pay. Walmart says it also offers most employees productivity bonuses and is working to adjust collective bargaining contracts to comply with the new labor law being passed. At the Mexico City store, Mr. Hernández, who earns $59 for his six-day week, says he hasn’t gotten a raise yet. Mrs. Martínez says the productivity bonuses she’s received from the company amounted to $10 every year or two.

The 58-year-old mother of four could use some extra money. She says her husband contributes from odd jobs he’s able to find, such as stringing up Christmas lights—but not in Mexico. To get that work, he had to cross the border.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Ben Holland at bholland1@bloomberg.net, Jillian Goodman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.