Erdogan’s ‘New Turkey’ Has Left Millions Unmoored

Erdogan’s ‘New Turkey’ Has Left Millions Unmoored

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The quiet is nagging at Hasan Gormez as he sips a traditional Turkish black tea outside a cafe in Yeniceabat, a hamlet about a two-hour drive south of Istanbul. “Back in the day, the village coffee shop was filled with happy farmers joking around,” says Gormez, 48, who works 30 acres he inherited from his family. “Now everyone here is upset about the economy, and our kids are gone.”

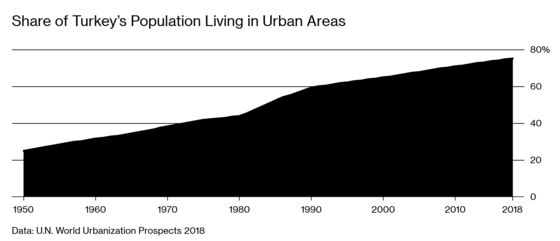

The “New Turkey” President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been touting ahead of local elections on March 31 is a nation emboldened by its economic clout, even though a recession has cut short the expansion that had gone on almost uninterrupted since late 2009. Yet by hitching development to consumer spending and urban infrastructure projects, Erdogan has also accelerated one of the biggest population shifts in modern Turkish history, dislodging 2 million people from agriculture jobs to look for work in the big cities.

The share of the workforce employed in farming has almost halved, to 15 percent, during Erdogan’s 16 years in power, while an area of arable land the size of Holland has been taken out of cultivation. As villages have emptied, Turkey’s self-sufficiency has withered: The Economist Intelligence Unit’s latest Global Food Security Index ranked it 48th of 113 nations, below Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and other desert states.

Erdogan got his political start in the 1990s as mayor of Turkey’s commercial hub, Istanbul, and built his base among working-class city dwellers by developing infrastructure and extending social support. Yet even Turkey’s urban centers have emerged as battlegrounds in the local elections scheduled for March 31, the president’s first test at the ballot box since he assumed vastly expanded executive powers last year. The longtime leader has a track record of swinging voters his way as polling day nears, but this time, Turks are casting ballots with the economy shrinking, jobs disappearing, and food prices rising. The move away from agriculture is haunting Erdogan, whose ruling AK Party is in danger of losing its quarter-century hold on the capital, Ankara.

Erdogan still wields immense influence in the countryside, where people have embraced his attempts to break with Turkey’s more secular recent history and return to a government steeped in Islam. But the political winds are starting to shift against Erdogan there, too. Once an agricultural powerhouse, Turkey has grown reliant on cheaper food imports over the years, making farming less profitable and adding to the ranks of exiles from the villages. That didn’t seem to matter much until the lira’s meltdown last summer made those imports increasingly expensive, driving up food inflation at the fastest pace since at least 2004. “The government has left the agriculture sector to its fate,” says Nuri Karaca, a 71-year-old farmer from Bursa who’s also the head of a local association of meat producers. “He cares more about his voter base in the slums of large cities than citizens in farmlands.”

A farmer and onetime loyal AKP voter, Erdinc Sari, 46, says it’s time for a change. This year, he’ll back a candidate for the main opposition party in Bursa, a former Ottoman capital and Turkey’s fourth-biggest city. In part due to imports, the price of animal feed has more than doubled in the past three years. The government provides 1,500 liras ($274) in annual support, barely enough to cover 10 percent of what Sari spends on fertilizer alone. “I have two kids—one son, one daughter,” he says. “I don’t want them to become farmers like their dad.”

Erdogan’s response to rising prices has been to lurch away from the free market toward state-led interventions. Municipal police have raided warehouses and hounded retailers, blaming hoarders for runaway prices, while municipalities have set up stalls to sell state-subsidized food, competing directly with privately owned retailers that need to profit to survive. The law enforcement crackdown was enough to slow the upward momentum in prices in February. But even after decelerating to a year-over-year rate of 29.3 percent last month, from 31 percent in January, food inflation is running at more than double the central bank’s yearend forecast. Direct government interventions, such as threatening and prosecuting banks or retailers who raise their prices, “conflict with the very notion of a market economy,” says Cristian Maggio, head of emerging-market research at TD Securities in London.

The effects of the lira’s rapid fall last August continue to ricochet between banks and manufacturers. Businesses that loaded up on foreign debt are having trouble making ends meet since the lira weakened. Propped up by borrowing, some companies will be forced to restructure or close down. Industrial output has been dropping precipitously since September, shrinking by an average of almost 7 percent every month.

The government has also tried propping up the lira by pressuring banks not to facilitate bets against the currency by foreign fund managers.

Demand among consumers for credit has dried up, and people are dumping their liras for the safety of dollars, which they’ve taken to stashing under the mattress as clouds continue to gather over the economy. Only days before the election, Erdogan warned banks that they’d pay for stoking another surge in demand for hard currency. Meanwhile, the jobs in services and construction that turned millions of villagers into urban dwellers are disappearing fast. Unemployment has jumped for eight months straight; it’s now 13.5 percent, the highest level since 2009.

Every week since he lost his job six months ago, Muharrem Cinar, 51, has visited a local employment agency in Ankara. Disappointed each time, he’s been forced to borrow heavily from friends and family to pay for his children’s education. “I’ve never been unemployed for this long in my life,” he says. “I don’t even have money to buy bread.”

But it’s the youngest Turks who’ve been stung the most. A quarter of people aged 15 to 24 need jobs. Rabia Akman, 24, a nurse with four years’ experience, has also been unemployed for six months. “I don’t want to say I don’t have any hopes for the future,” she says. “But I’m scared.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Onur Ant at oant@bloomberg.net, Lin NoueihedPaul Abelsky

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.