The Rise and Fall of America’s Original Food Magazine

The Rise and Fall of America’s Original Food Magazine

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Once upon a time, Condé Nast editors ruled the Earth. They had town cars, an annual clothing allowance, and a canteen called the Four Seasons. Now, every season brings news of the shuttering or sale of a title—or the exit of one of those fabled editors. In 2018, the company said Chief Executive Officer Bob Sauerberg Jr. would be stepping down later this year. The year before, it lost $120 million, according to the New York Times.

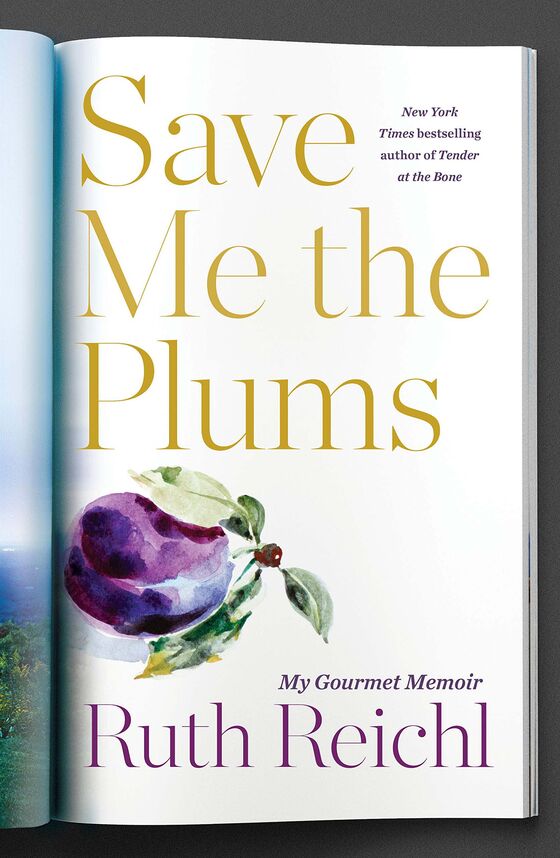

But from the 1990s to the late 2000s, New York’s social world spun around AnnaGraydonDavidPaige (the first names of the editors at Vogue, Vanity Fair, the New Yorker, and Architectural Digest, respectively). Fashion was Condé Nast Inc.’s calling card, but it also boasted the queen of food journalism, Ruth Reichl. The curly-haired Berkeley hippie was the era’s Julia Child, with a dash of Chrissy Teigen’s communications savvy. In April 1999, Reichl became editor-in-chief of America’s original food magazine, Gourmet. Her new memoir, Save Me the Plums (April 2, Penguin Random House), details her reign, which began when Gourmet’s core audience was the second-houses-with-horses set and lasted through a decade of ever-expanding horizons.

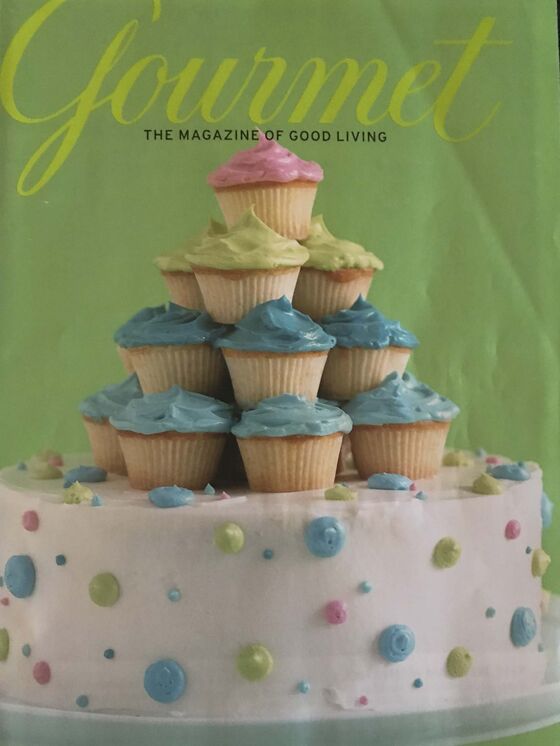

Reichl narrates cage-rattling decisions such as putting cupcakes on the cover (old-school readers rebelled; too down-market) and assigning articles to the likes of David Rakoff and David Foster Wallace. (Wallace’s article on the ethics of killing shellfish at the Maine Lobster Festival became the title essay in his book Consider the Lobster.) Meantime, Reichl reveals the challenges of being a wife, mother, and successful author with frequent book tour demands that she guiltily fulfills. Inevitably she arrives at September 2009, when Condé Nast’s late owner, S.I. Newhouse Jr., gathered Gourmet’s team to say he was closing it. Reichl raided the magazine’s wine cellar and summoned company cars to take the staff to her house for one last party.

After such books as Comfort Me With Apples, about her start in restaurant criticism, Reichl has an enthusiastic fan base—1.3 million of them devour her haiku-like tweets. These readers will be happy to know she’s pretty much always right in Save Me the Plums, whether she’s putting raw fish on the cover (considered art director suicide at the time) or sending pots of homemade chili to Sept. 11’s first responders. Occasionally she admits a mistake: Toward the end, when budgets were being slashed, she neglected to research the person who bought an auctioned dinner with her. It was hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, who wasn’t amused at her lack of interest in him.

The book is perhaps too light on what went into putting together Gourmet, a magazine that covered so much disparate ground it felt like it had ADD. But what is there are reminders of the things she and the magazine achieved: As the restaurant editor at rival Food and Wine, I was extremely jealous of the time she flew the entire staff to Paris so they could re-create the experience of French eating, cooking, and shopping in extraordinary detail and when she devoted an entire issue to Southern food legend Edna Lewis. Reichl was also the first print magazine editor to hire a full-time video producer to capture the work of a test kitchen and share simple tricks for, say, boning a fish. Seems obvious now, but she was way ahead of her time.

In the end, for all her efforts, Reichl and Gourmet came up against the industry’s conundrum: Magazines can’t remain the same and stay afloat, nor can they continually innovate, lest they lose their audience. And Gourmet’s test kitchen ran up vast bills: Recipe-testing costs averaged $100,000 a year, and the staff included 12 cooks and 3 dishwashers. It wasn’t unknown to test a recipe 20 times. (Try telling that to an Instagram chef.) And then there was the financial crisis.

A 2009 Newsweek article guessed that Condé Nast ad revenue losses might hit $1 billion that year. Thus, Gourmet’s demise was predictable—but still shocking, and not only to foodies. For a decade, Reichl used her talents and platform to push the culinary universe to a more democratic place that championed cooking while spotlighting real-world food issues. And it transformed elevated cooking into the realm of the achievable. Now the idea that everyone can be a home chef is central to our public lives on social media. But momentary videos on YouTube, “quick-fire challenges” on TV, and well-composed photos on Instagram rarely tell the story behind the dish. Reichl endorsed doing it the right way; whether a recipe was simple or ambitious, she urged readers to learn more about what they were doing in the kitchen.

Although her megaphone is smaller, her voice remains one of the most trusted in our disparate food universe. Reichl’s book reminds us of the time when you could pick up a magazine and feel simultaneously starved and sustained.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Gaddy at jgaddy@bloomberg.net, Chris Rovzar

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.