Forget Cherry Blossoms: The Real Reasons to Go to Kyoto Right Now

Forget Cherry Blossoms: The Real Reasons to Go to Kyoto Right Now

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- You want to know what Japan is? This is Japan,” my friend Misa Matsuda said, plunging her chopsticks through the oil-slick stillness of her soup broth, exhuming long tresses of noodles from deep below. It was 2003, and Misa and I had a nightly ritual as teenage students in Tokyo: fortifying our stomachs with a steaming bowl of “mayonnaise ramen,” enhanced with a thick dollop of the condiment for extra richness, before a long night out clubbing around the frenetic streets of Shibuya Crossing.

At the time, I was on the hunt for a way to describe to my friends at home what made the country tick. What they were seeing on TV was the stereotypical (and reductive) Harajuku Girl, a look made popular in the U.S. by Gwen Stefani. As Misa put it, our hearty midnight snack was the actual answer. Originally from China—the dish was called Chinese soba until the 1950s—ramen was continually refined by the Japanese, eventually becoming synonymous with its adopted homeland. Like Buddhism and tea ceremonies, it was borrowed from abroad, assimilated, and perfected with time. The idea has stuck with me since.

For much of Japan’s modern history, Tokyo has been the hub of cool, creative energy—the place where you could do something as subversive as adding mayonnaise to ramen. Kyoto, its ancient capital, has been a fortress of steadfast cultural preservation. So it might seem unexpected that in spite of all the infrastructure required for Tokyo’s 2020 Olympic Games, it’s Kyoto that’s emerging as a hotbed for innovation, particularly where restaurants, art, and accommodations are concerned. By the end of the year, Kyoto will be home to at least three highly anticipated hotels, including, most notably, Japan’s first Ace Hotel. Designed by Kengo Kuma and located in the city center, it promises the chain’s trademark breed of carefree cool. Aman, known for its out-of-this-world luxury resorts and $2,000-a-night price tags, makes its debut in November near the iconic Golden Pavilion temple. And the Park Hyatt brand is soon opening 70 rooms in a four-story building near the Kiyomizu-dera temple complex.

Local artist Shiro Takatani, who co-founded the influential art collective Dumb Type, isn’t surprised that his city is heating up. “Tokyo may be Japan’s modern capital, but Kyoto retains a youthful energy,” he says. “It’s a college town at its core.” There are at least 30 accredited educational institutions in this city of 1.5 million, making it a breeding ground for ideas—often ones that engage with the country’s oldest customs.

Takatani recalls days spent as a student in the 1980s hashing out grand theories with friends in Kyoto’s famed cafes. Fast-forward, and he and his cohorts are collaborating on multimedia performance art and video, using their traditional education to create commentary on modern Japanese society. In recent years they’ve gained global visibility, even showing works at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

French photographer and Kyoto transplant Lucille Reyboz agrees that the city’s long-simmering creative spirit has finally reached a rolling boil. In 2013 she and her husband, Yusuke Nakanishi, founded an international photography festival called Kyotographie, which hosts exhibitions inside centuries-old buildings, many of them abandoned or disused. “We want to both honor the city’s history and establish it as a leading light of international culture,” she says. Last fall the Kyoto prefectural government and chamber of commerce gave Reyboz and Nakanishi an annual local honor, the Kyoto Creator Grand Prix, for their artistic leadership.

Reyboz’s British friend David Croll, an expatriate entrepreneur, is co-founder of the Kyoto Distillery. Two years ago he started bottling Ki No Bi, Japan’s first superpremium gin, in a district known for its proud tradition of sake brewing. Its proprietary recipe capitalizes on kyo-yasai, the unusual heirloom vegetables and botanicals of the Kyoto region. Ki No Bi has begun to replace whisky as the tipple of choice at cocktail bars around town. Among them is the gin-centric, Alice in Wonderland-inspired Nokishita711, as well as Bar Rocking Chair, run by a world-champion bartender.

Chefs are similarly applying refreshing dashes of whimsy to kyo-yasai and kaiseki cuisine, a traditional series of small, intricately prepared dishes that dates back at least 1,000 years. The always-packed Awomb condenses the kaiseki experience onto a single bento platter; it’s so photogenic, the restaurant has to enforce a dining time limit on its Instagram-obsessed patrons. At Soujiki Nakahigashi, the hardest reservation to score in Kyoto, the namesake chef Hisao Nakahigashi designs each day’s menu around the produce he personally forages on the nearby mountainside. But whereas most kaiseki meals are carefully structured to follow a prescribed progression, Nakahigashi allows room for improvisation. Overhearing that I live in the Big Apple, for instance, he prepares a course of mountain vegetables gently submerged in a clear broth. “New York!” he exclaims with a wink as he presents my dish. In Japanese, the name is a double-entendre—nyu-yoku means “taking a bath,” like the vegetables in my bowl.

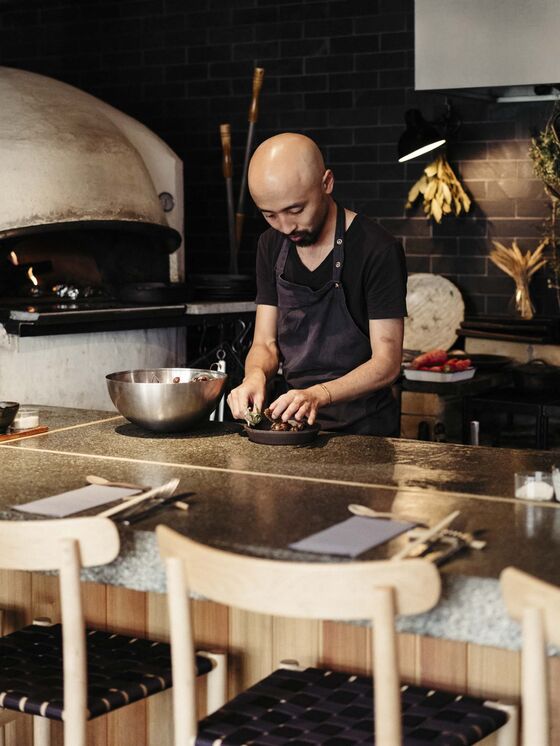

One of Nakahigashi’s protégés, Yoshihiro Imai, has a more renegade interpretation of kaiseki cuisine. At his restaurant, Monk, the parade of courses marches out of a kilnlike oven and culminates in … a pizza. Monk is the culinary equivalent of the Kyotographie photography festival: Imai reveres tradition while dabbling with international tastes, techniques, and trends. He makes his perfect Neapolitan-style pies with high-grade Japanese flour and kyo-yasai toppings such as manganji pepper (a thicker shishito), red kintoki carrots, and bulbless kujo scallions.

“Usually one pizza is the right amount of food for two people,” Imai says, as I dine alone among the couples at his countertop. “But I’ll make a whole one just for you.” He soon slides a bubbly crust my way, laden with a pulpy eggplant pesto and fresh basil leaves. At the end of the meal (and after a rich mouthful of espresso brewed from beans roasted in his oven), he packs up my leftovers. “It’ll make a great snack for later,” he says—perhaps one that’s even better than mayonnaise ramen.

When the Penthouse Suite Isn’t Enough

A residence fit for a king—nay, emperor—the rambling temple complex of Ninna-ji was established in the 880s, during the Heian period. For centuries, the temple (which is now protected by Unesco) only welcomed members of the imperial family for overnight visits, but now the general public can stay as well.

For a starting price of 1 million Japanese yen ($9,000) a night, guests get dinner, breakfast, and butler service within a temperature-controlled samurai residence; in traditional fashion, the beds consist of plush futons on tatami mats. Morning brings a private prayer session on the temple grounds with Ninna-ji’s resident monks.

It’s all the brainchild of industry veteran Ken Yokoyama. His latest endeavor, Weft Hospitality, champions tourism-driven revenue streams for Kyoto’s donation-poor temples and shrines. Book overnights through Weft’s tour operator, InsideJapan.

The ‘Little Kyoto’ You Didn’t Know Existed

Situated in the arable land of western Japan, Kanazawa was the country’s largest producer of rice during feudal times, making its rulers, the Maeda clan, some of the nation’s richest. Today, the vestiges of their wealth—well-preserved wooden shrines, samurai quarters, and geisha districts—have earned the city its “Little Kyoto” moniker.

All that is within easy access of Japan’s major cities following the 2015 completion of the Hokuriku bullet train, making Kanazawa a magnet for young Japanese weekenders who dress up in traditional yukatas and kimonos for the trip. Foreigners are catching on, thanks to a spate of new boutique hotels, including Uan Kanazawa, Kumu, and the two-room Auberge Maki No Oto.

Another local claim to fame? Gold leaf production. (The town supplies 99 percent of the craftsmen’s needs in the country.) You’ll see it everywhere in the historic Higashi Chaya district—even draped onto cones of vanilla soft serve.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Rovzar at crovzar@bloomberg.net, James Gaddy

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.