Two Messy Paths to the Same Emerging-Market Turmoil

Two Messy Paths to the Same Emerging-Market Turmoil

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- There’s no politician more devoted to cheap money than Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and no country that charges higher rates on its money right now than Argentina.

That’s just the start of the contrasts between two governments in the eye of an emerging-markets storm. Both economies are struggling with high inflation and falling currencies and are at risk of recession. On almost every count, Argentine President Mauricio Macri has done the things investors typically demand in such situations— even if he’s sometimes botched the implementation. Since June, he has hiked interest rates to a world-high of 60 percent, turned to the International Monetary Fund for help, and announced sweeping budget cuts for 2019—the year he’s up for reelection.

Unfortunately for Macri, all those approving investors won’t be voting, and he may end up getting punished for what the markets see as his virtue. “The way he’s responded wins plaudits from markets,” says William Jackson at Capital Economics. “Not from voters.”

Meanwhile, Erdogan has taken the opposite approach, thumbing his nose at the markets along the way. He has repeatedly warned his nominally independent central bank against raising rates, including in the lead-up to the bank’s unexpected hike on Sept. 13, and he resumed the attack today. Erdogan also awarded himself new powers over monetary policy. In case they weren’t enough, he put his son-in-law in charge of the economy.

On top of that, there are no immediate political costs to Erdogan’s defiance. He won reelection for an additional five years in June, just before the worst of the lira’s slump. Despite the different paths their leaders have taken, the two countries’ currencies, the lira and the peso, have suffered the same fate: Both are down more than 35 percent.

Turkey’s central bank has been “goaded into doing as little as it can get away with,” says Rachel Ziemba, an emerging-market specialist at the Center for a New American Security, speaking before the latest rate hike. The government hasn’t delivered “meaningful” budget cuts, raising doubts about its commitment to stopping the bleeding.

At least Erdogan has a convenient bogeyman to blame it on. The biggest hit to Turkish markets came after President Donald Trump, enraged by the detention of an American pastor, slapped sanctions on his NATO ally. “It plays into Erdogan’s narrative of external actors undermining Turkey,” says Ziemba.

Trump backed Macri when the Argentine leader sought urgent changes to a $50 billion IMF loan (the biggest ever) agreed just three months earlier. Macri wants more cash upfront to halt the peso’s slide. The IMF has signaled he’ll get it. “Argentina doesn’t really have enemies in D.C.,” says Ian Bremmer, president of Eurasia Group. “Erdogan doesn’t really have that many friends.”

But history has made IMF money toxic in Argentina. The country crashed out of a Fund program in 2001. It defaulted on debt, suffering economic depression and social unrest—and swung sharply to the political left. For more than a decade, until Macri’s narrow election win in 2015, it was governed by free-spending populists.

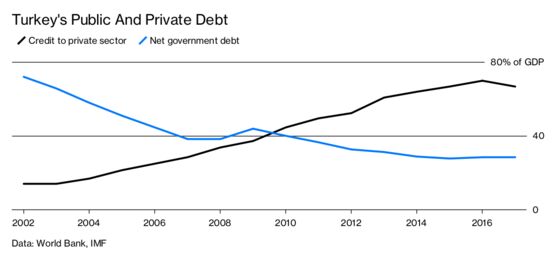

Turkey also endured its worst financial crisis under IMF tutelage in 2001. Established political parties were wiped out, opening a path to power for Erdogan, who’s been in charge ever since. He stuck with a revised IMF program in his early years—and absorbed one lesson, even after paying the Fund back. Unlike his budget-busting 1990s predecessors, Erdogan has never run his economy on government money.

He ran it on bank money instead. As public debt and deficits dwindled and inflation came down, private credit surged. The lending boom has barely halted.

Erdogan’s hatred of high rates has been linked to Islamic proscriptions on usury, or the eccentric financial theories he sometimes endorses. But cheap credit is just the fuel that powered Turkey on his watch. He’s about as likely to disavow it as the Saudis are to enthuse about electric cars.

Eventually, keeping the debt machine moving became a strain, requiring ever-growing political pressure on the central bank to keep borrowing costs low. That’s left Turkey awash in debt that’s about to get harder to repay. The lira’s slump spells trouble for the many businesses that owe money in dollars or euros. Higher rates to prop up the currency would put the squeeze on lira borrowers.

Some kind of bailout may be needed if companies start to go under, says Jackson at Capital Economics—but Erdogan can probably afford that: “The redeeming feature for Turkey is the government balance sheet is quite strong.”

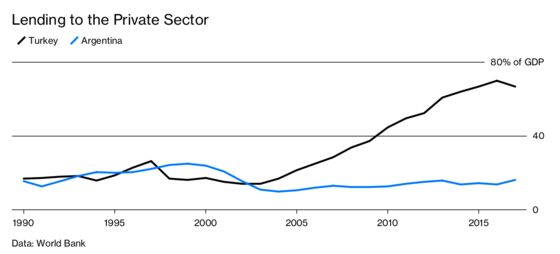

Like Erdogan more than a decade earlier, Macri also inherited shaky public finances. He might have hoped for the kind of private-credit liftoff that Turkey enjoyed in the mid-2000s. But that was boom time everywhere, as investors piled into emerging markets. Now they’re pulling out. With Argentina’s high inflation and history of volatility, the credit never flowed.

Even if times get tough, Argentines may not be ready to throw Macri overboard next year. Memories are still fresh of how his populist predecessors ran the economy into the ground. The populists have fragmented since losing power, and they’re under fire over a corruption scandal.

Still, Macri is short of tools to engineer voter-friendly conditions before election day in October next year. Committed to austerity, he doesn’t have any government money. With rates at 60 percent, there won’t be much bank money either. He’s going to have to run his election economy on IMF money. In Argentina, of all countries, that’s a high-risk strategy.

Jackson, of Capital Economics, struggles to sketch a scenario in which things work out for Macri and Argentina. The president somehow wins reelection; the IMF program holds; the deficit narrows; inflation comes down; borrowing gets a bit cheaper; and credit is available for businesses and households to rekindle growth.

“It’s a lot of assumptions,” he admits. “It’s quite hard to see how this happens. The risk of all this falling apart is quite high.” —With Patrick Gillespie

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Philips at mphilips3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.