Trade, Tariffs, and Tedium: A Year at the Front of Nafta Talks

This Is Your Brain on Nafta

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It was a perfectly Trumpian moment. On the morning of Aug. 27, reporters and top White House officials crowded into the Oval Office to witness the president announce an agreement with Mexico. “Big day for trade, big day for our country, a lot of people thought we’d never get here,” Trump said as he settled in behind his desk. After more than a year of contentious negotiations with Canada and Mexico to redo the North American Free Trade Agreement, Trump finally had a deal—though not quite the one he promised. It included only Mexico, not Canada.

Ever the showman, Trump was eager to make a public display of calling Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto as TV cameras rolled. He punched a button to get Peña Nieto on speakerphone. “Enrique?” Instead of the Mexican president, there was silence on the other end as cameras snapped away, capturing the awkward moment. “Hellooo?” Nobody was picking up. As aides scrambled to fix the connection, Trump’s TV triumph had become a scene from the HBO comedy Veep.

In a sense, the moment encapsulated the frustrating year of Nafta negotiations that preceded it: slapped together, barely coordinated, and wildly oversold—and at the mercy of a fickle president hungry for a “win.” Although Trump touted the Mexican agreement as one of the largest trade deals ever struck (it’s not), Wall Street analysts were decidedly meh. In a note to clients, Goldman Sachs concluded: “We do not expect the revised terms to have substantial macroeconomic effects in the U.S. if they do take effect.” The skepticism stems from doubt the agreement will be passed by Congress—where many legislators want Canada to be part of it.

Trump’s trade czar, Robert Lighthizer, probably had a different timeline in mind when he opened talks to renegotiate Nafta last summer. His plan had been to browbeat Canada and Mexico into quick submission before moving on to tackle China. Instead, his hopes of a shock-and-awe win gave way to soul-sapping trench warfare.

The idea of speeding through a Nafta redo was never realistic. While all three countries want to update the 24-year-old deal, objectives were always out of sync. Canada and Mexico want to modernize and update Nafta, while Trump and Lighthizer simply want to make it a better deal for the U.S.

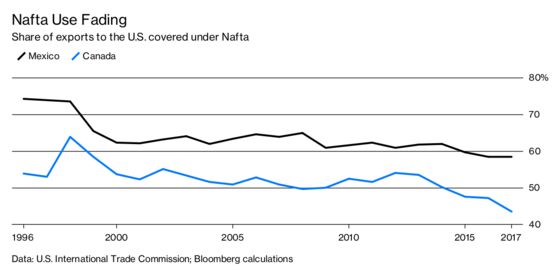

Although the three countries trade more than $1 trillion of goods each year, much of it fueled by Nafta, Lighthizer and Trump aren’t convinced it’s ultimately to the benefit of the U.S. That’s a throwback to the view of free trade from the late 1980s and early ’90s, when Nafta passed amid skepticism. At the time, Lighthizer was a rising trade lawyer who, in his 30s, served as deputy trade representative for Ronald Reagan. Although economists now widely credit Nafta with spurring growth in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, Lighthizer and Trump aren’t among the converted. “They’re definitely on the fringe,” says Gary Hufbauer, a trade fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Trump began the talks by threatening to kill the pact—and to hit Canada and Mexico with tariffs paid, incidentally, by U.S. consumers. Any leader has the power to quit Nafta with six months’ notice. His threat helped make Canada and Mexico allies. As talks geared up, the two countries readied for a fight and linked arms against a U.S. onslaught—despite calls in Canada for Minister of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland to throw Mexico under the bus. “There was an understanding by both countries that it would serve them well to work together and provide a bit of a common front,” says Bryan Riley, director of the free-trade initiative for the National Taxpayers Union, a free-trade group in Washington.

Negotiating teams met early on every couple of weeks as talks rotated among locales—a beautiful hotel in Mexico City, a dingy one in D.C., a cavernous old city hall in Ottawa, complete with school buses for transportation and bagged lunches. The Nafta ministers for each country—Lighthizer, Freeland, and Mexico’s Ildefonso Guajardo—tried to be friends, kicking things off with dinners and a book club. But the effort fell apart almost immediately; Lighthizer simply doesn’t seem to like Freeland, a former journalist and globe-trotting Rhodes scholar who riled him by lobbying Capitol Hill and stirring up opposition to his trade agenda. While Guajardo was given two cakes when negotiations fell on his birthday, Freeland was left out of talks on hers.

Beyond the personal animosities, talks were bogged down by brain-numbing details. Entire sessions can be spent arguing over the meanings of “and” and “or.” Each round lasted a week or so, and—despite their importance—had the same atmosphere as dreary hotel industry conventions: Everyone woke up to the same boring breakfast buffet, then drifted off to rooms for daylong, unproductive talks before ending at a bar for drinks to wind down. This was the Nafta party circuit.

During the negotiations, the levels of engagement were uneven. Canadians and Mexicans were generally empowered to haggle, while the U.S. at first had only skeletal staffing. And when senior Trump representatives showed up, some didn’t care to bargain, essentially sliding take-it-or-leave-it offers across the table. Canadians privately grumbled about the U.S. not doing its homework, while the U.S. grumbled about Canada and Mexico digging in.

By the time talks approached their first anniversary on Aug. 16, negotiators had made their way through less than half of Nafta’s chapters, mostly low-hanging fruit. The hard stuff—auto manufacturing rules and whether the deal would include a sunset clause—had yet to be tackled. With impasse after impasse, hope had begun to fade for any sort of deal, and talk shifted to whether Trump would cancel Nafta outright. “It was almost a wasted year,” Riley says. It still might be.

What changed things was Andrés Manuel López Obrador, aka AMLO, the leftist who won Mexico’s election in July. Coupled with Trump’s falling out with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau after the Group of Seven meeting in June, AMLO’s victory not only gave the Mexicans and the U.S. a deadline to race for—he takes office on Dec. 1—but also provided Lighthizer with an opening to split the Mexicans off from the Canadians by focusing on higher wages for Mexican autoworkers.

Lighthizer essentially froze out the Canadians. While the Mexican team spent the late summer in Washington, with technocrats negotiating around-the-clock at U.S. Trade Representative headquarters around the corner from the White House, the Canadians were absent for months, forced to keep in touch from afar. After Trump announced the deal with Mexico, Freeland flew from Europe to Washington to restart talks on Aug. 28.

The Mexican gambit ran counter to what was supposed to be Trump’s primary objective for renegotiating Nafta: cut the $70 billion U.S. trade deficit with Mexico and stop the southward flow of manufacturing jobs. He at first talked only of “tweaks” for Canada while railing against Mexico. Canada is by far the world’s top buyer of U.S. goods and has a basically balanced trade relationship, making it an unlikely target for a trade-deficit-obsessed president. Yet, as talks dragged on, Trump’s priorities shifted, and his patience, particularly with Trudeau, was tested. A savvy political operator, Lighthizer was able to pivot from criticizing Mexico to embracing Nafta’s southern partner.

Now, Canada is back at the table and clearly under pressure to make concessions and get a deal. Freeland could still use the U.S. and Mexico’s urgency—Trump’s desire for a win; Peña Nieto wanting to tie things up before AMLO takes office—to her advantage. For example, in any new agreement, Canada wants to preserve antidumping panels, essentially third-party tribunals where disputes can be settled. Over the years, the country has a good record of winning these fights. Lighthizer is bent on killing them. “That provision will not exist,” he said on Aug. 27. Another issue is Canada’s dairy industry, which isn’t part of Nafta. Trump has fixated on destroying the country’s system of production quotas and tariffs. Trudeau defends the system but hasn’t ruled out using it as a bargaining chip.

Then there’s Congress. Nafta talks have proceeded under what’s known as Trade Promotion Authority, which grants trade powers to the president. Lighthizer wants to give notice of a pact before the end of August, with or without Canada. Yet it’s unclear whether a bilateral agreement with Mexico would fall under this provision and allow for a simple majority vote by Congress. Canada has allies among a few key Republican senators, including Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania, John Cornyn of Texas, and Utah’s Orrin Hatch, chair of the powerful Senate Finance Committee, who want to include it in a final deal. “There will be elements of this understanding which I think Congress will seriously question, as will the Canadians, so I think we’re still a fair distance away from a new Nafta 2.0,” Hufbauer says.

For Trump, the goal is more about political perceptions than the details. “A lot of this is optics vs. procedure. This administration could probably pull off something on the optics, but I don’t think they’re going to get congressional buy-in on the procedure,” says Welles Orr, an assistant U.S. trade representative under George H.W. Bush. “Congress, I can assure you, has been making it very clear to the administration to not frankly screw up.”

A new Nafta is still months away and may come with a new name. Congress probably won’t get a chance to vote on a final deal until 2019. The signal, however, is clear—when it comes to negotiations with Trump, no friendship is safe. —With Eric Martin and Andrew Mayeda

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Philips at mphilips3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.