The Stunning One-Year Turnaround of GM’s German Castoff

The Stunning One-Year Turnaround of GM’s German Castoff

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The giant Opel factory in Rüsselsheim, an industrial city a half-hour’s drive west of Frankfurt, appears little changed from last summer: Employees still wear “We are Opel” T-shirts. The melody that rings out every few minutes, signaling that someone needs assistance, is the same. Body panels for Insignia sedans and Zafira minivans still follow the same yellow marks on the concrete floor on the way to their “wedding,” where workers add the engine and transmission to the frame.

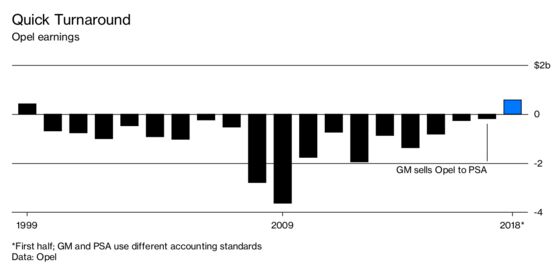

One thing, though, is dramatically different: The cars that roll off the end of the line are sold at a profit. “When I see friends in the pub, I can finally put the keys to my Opel on the table with pride again,” Matthias Deschamps, a 33-year assembly-line veteran, says looking over the production floor. In July, when the carmaker reported its first profit since 1999, “there was a big sigh of relief.”

The end of Opel’s run of futility—$20 billion in red ink over two decades—came less than a year after General Motors Co. sold the company to PSA Group, the maker of Peugeot and Citroën. PSA Chief Executive Officer Carlos Tavares, who was ousted as Renault SA’s chief operating officer after publicly seeking the top job at GM, has made peace with skeptical unions and figured out how to profitably produce low-margin cars in a high-cost country. Opel posted earnings of €502 million ($583 million) in the first half of this year, vs. a €179 million loss from August to December 2017, the first five months under PSA. Opel’s 5 percent profit margin is now on par with Volkswagen AG’s namesake brand, which boasts double the market share in Europe and sells more than five times as many cars globally.

As he did at Peugeot, Tavares avoided angering the staff with expensive and disruptive factory closings. Instead, he secured an agreement with labor to trim salary costs by reducing the standard workweek to 35 hours from 40 and eliminating 3,700 jobs through buyouts. He’s cut output—Opel’s European deliveries dropped 6.2 percent in the first half of this year—to stem losses and focus on cars customers actually want to buy. In Rüsselsheim, that means assembling 42 vehicles per hour instead of 55.

For PSA, Opel offers an opportunity to survive in the ultracompetitive mass-market auto business by spreading costs across more vehicles. And for Tavares—a notorious penny-pincher who flies discount airlines, urges colleagues to turn off office lights when they leave, and abandoned the prestige of a headquarters in central Paris for the suburbs—it was another chance to prove himself.

In contrast to the flybys typical of GM executives, his first official visit to Rüsselsheim a year ago became a six-hour inspection tour as he took a deep dive into Opel’s operations, initiating part-by-part comparisons with Peugeot and Citroën. The review uncovered hard-to-justify excesses such as the 57 possible infotainment systems for the Corsa, a bread-and-butter hatchback that starts at about €12,000. That’s being reduced to fewer than 10. Similarly, Corsa buyers will have nine windshield and wiper options, down from 16. “Under PSA, there’s a stronger focus on reducing complexity,” says Flavio Friesen, a director for vehicle engineering who’s worked at Opel for 11 years. “That’s helped us get more efficient.”

PSA faces more challenges, as it’s highly reliant on the saturated European market where it competes with global giants such as Volkswagen, Toyota Motor, and Renault-Nissan. The group’s brands largely target the same price-conscious consumers, and Opel’s reputation needs burnishing after GM’s tumultuous reign. The Detroit company sought to sell the brand in 2009 but pulled the plug at the last minute to maintain a presence in Europe, and Opel had five chiefs in its last seven years under GM. PSA must figure out what to do with the Vauxhall nameplate, which sells almost identical cars in Britain, adding cost and complexity to its operations. And Opel will have to make the transition to electric vehicles under the guidance of PSA, which has lagged behind rivals such as Volkswagen and Renault-Nissan. “Opel is not done,” says Stefan Bratzel, director of the Center of Automotive Management at the University of Applied Sciences in Bergisch Gladbach, Germany. “The challenge is to combine good numbers with good marketing and change their image.”

While Tavares has called the ahead-of-schedule profit a “first very positive sign” of Opel’s recovery, he cautions that achieving Peugeot’s goal of €1.7 billion in annual savings from the deal will depend on combining the companies’ engineering teams. The revamped Corsa, due next year, will share most basic parts and technical elements with compacts from PSA’s French brands, and other models will soon follow.

And then there are Tavares’s long-term goals, including an eventual return to the U.S. and transforming PSA from a European specialist to a global player. While he won’t rule out further acquisitions, he says PSA doesn’t need to grow dramatically to be successful. “More than volumes, profitability is the most important element,” he says. “I prefer agility and efficiency to being the biggest car group.” —With Leonard Kehnscherper

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net, Chris Reiter

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.