Big City Housing Doesn’t Have to Be So Expensive

Housing prices needn’t be high just because an area is hemmed in by water or mountains.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The one-story house for sale on Oak Court in Menlo Park, Calif., is 88 years old and 830 square feet, with two bedrooms, one bathroom, a detached one-car garage, and no air conditioning. Almost anywhere else it would be the startiest of starter homes. But because it’s in Silicon Valley, where the supply of housing is far short of the demand, the bungalow was listed in mid-August for $1.575 million.

Imagine if ants put up barriers that stopped other ants in their colony from getting to a sugar cube. That’s what Americans are doing to one another by making housing impossibly expensive in the very places, such as Silicon Valley, that most need fresh talent.

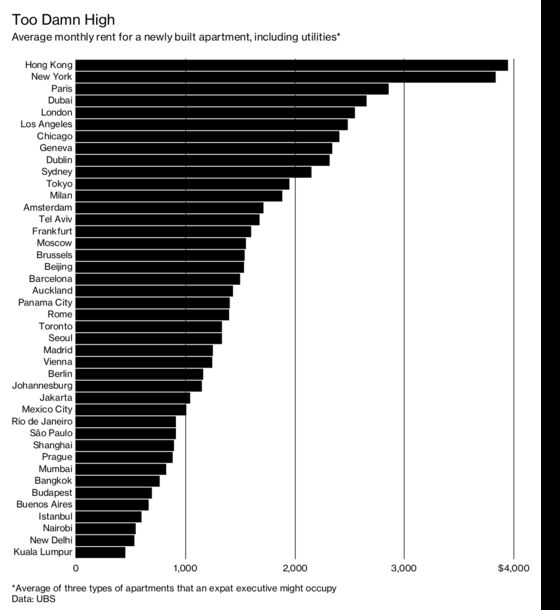

Housing prices needn’t be high just because an area is hemmed in by water or mountains, as Silicon Valley is at the end of San Francisco Bay. After all, you can always build upward without wiping out green spaces and historical treasures. Rather, high housing prices are the outcome of a strategy by incumbent homeowners to keep a lid on construction. Keeping cities frozen in time, only more expensive, is great for homeowners and bad for just about everyone else, including local employers and the people who would come to work for them but can’t. While the problem is most pronounced in Silicon Valley, it exists in San Francisco, London, New York, Tel Aviv, Tokyo—name your global hot spot.

Affordability matters because cities have never been economically more important. Biotech companies choose to cram together in San Diego and Cambridge, Mass.; cybersecurity firms are cheek by jowl in Israel’s Silicon Wadi; consumer-electronics companies want to be near one another in the former fishing village of Shenzhen, China.

Constraints on housing prevent people from joining, and contributing to, clusters of innovation. A new paper by economists Chang-Tai Hsieh of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and Enrico Moretti of the University of California at Berkeley found that restrictive zoning in Silicon Valley, San Francisco, and New York “lowered aggregate U.S. growth by 36 percent from 1964 to 2009.”

Thirty-six percent is kind of a big number. Says Hsieh: “If you compare it to all the things our political system talks about, this is just huge relative to everything else.”

The good news is that cities don’t have to be prohibitively expensive. The trick is to form a broad coalition for what pro-housing activists call Yimby (yes in my backyard) by ensuring that the benefits will be enjoyed by all, or almost all. More housing can help wealthy landlords, who benefit from the right to put more housing units on a given block, as well as low- and moderate-income families, whose rents come down when the supply of rental housing goes up.

To be clear, not every city with a housing shortage is economically thriving. Delhi, Jakarta, Lagos, Manila, and other megacities have different issues to deal with, including an influx of desperate people from rural poverty. We’re talking about First World problems here: how to cope with the complications of prosperity.

One recent success story is Mountain View, Calif., the home of Google parent Alphabet Inc. In December the City Council approved a plan for the area around the Googleplex that allows for construction of almost 10,000 homes, up from zero in the original proposals. Leonard Siegel, who was vice mayor then and is mayor now, says the city is locating homes near office space rather than trying to jam them into older neighborhoods. “Many people are perfectly happy for us to build housing near Google, because it’s not in their backyard,” he says.

Mountain View officials insisted that developers make 15 percent of the homes affordable, and they’re charging them fees to cover the cost of new public infrastructure such as transportation and sewer lines. “The way I told one developer, ‘We’ll find out if we piled on too much,’ ” Siegel says. “ ‘I want to load your back with straw, and when it starts to break, pull one straw off.’ They said, ‘I understand.’ ”

Some market purists argue that building affordable housing is unnecessary. Filtering theory says that even the construction of luxury housing will ultimately benefit the poor because the rich will move into the new units, freeing up their old dwellings, which will be occupied by the middle class, who in turn will make their old homes available to the poor.

Filtering really is a thing, and it works in the aggregate. But in any given neighborhood, lower-income renters are right to fear that gentrification will price them out of their home. So they oppose new construction, which only exacerbates the citywide shortage. Case in point: A California Senate bill to allow for denser construction along transportation corridors, backed by the Yimby movement, failed earlier this year over concerns about displacement of the poor.

That’s why making sure everyone benefits is essential. Rent control is anathema to most economists, but if applied only to existing housing, not new units, it can tamp down political opposition to fresh development without discouraging construction. Another effective approach is inclusionary zoning, which guarantees that a certain share of development will be affordable. The trick is not to lay so many requirements on developers that they back out and nothing gets built; not every mayor can afford to be as demanding as Mountain View’s.

Finally, outright construction of public housing can make sense. Does that sound socialist? Consider that more than 80 percent of residents in Singapore, the free-market city-state, live in government-built housing. This year the World Bank praised the food courts in Singaporean housing, known as hawker centers, “where all income classes and ethnicities meet, socialize, play, and dine together.” At least two hawker centers, it said, have a Michelin star.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson has one good idea: to use the lure of HUD dollars to get cities to ease zoning rules and permit more construction. But Carson hasn’t earned the support of advocates for low-income housing because he also wants to scale back an Obama-era rule requiring cities to work toward desegregation, which he once decried as “social engineering.”

Ydanis Rodriguez, 53, can identify with both sides of the Nimby struggle. He was born and raised in the Dominican Republic and moved as a teenager to Inwood, a neighborhood at the northern tip of Manhattan. He became a leader of 2011’s Occupy Wall Street movement. Now a New York City councilman, Rodriguez is a fierce advocate for his low-income constituents, many of whom are fellow Dominicans. When the city announced a plan to upzone Inwood, allowing for taller buildings and more market-rate housing, many of his constituents opposed it, fearing that gentrification would force them out. Rodriguez, controversially, came out in favor of the plan. He argued that it would keep low-income people in Inwood by constructing thousands of units of subsidized housing in addition to market-rate buildings.

“It hurt,” Rodriguez says of the accusations that he was selling out his own people. But when the upzoning passed the City Council on Aug. 8, he says, “I went to sleep in peace that night.”

The upzoning of New York under a succession of mayors, including Michael Bloomberg (founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, which owns Bloomberg Businessweek) and Bill de Blasio, is evidence that a big city can burst the bonds that limit growth. For more evidence, see La Défense in Paris, Canary Wharf in London, Pudong in Shanghai. Growth can be messy, but it’s better than stasis, which pretty much assures that supercities will fall short of their potential. “Arguably,” Harvard economist Edward Glaeser wrote in a Brookings Institution paper last year, “land use controls have a more widespread impact on the lives of ordinary Americans than any other regulation.” The most important policy for cities is to let them grow.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net, Max Chafkin

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.