Microsoft Bug Testers Unionized. Then They Were Dismissed

The subcontracted workers were challenging their termination, but they couldn’t hold out.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Silicon Valley’s contract labor has become a hot political topic, as a slew of potential Democratic presidential candidates sponsor legislation that could force companies to negotiate with more workers they claim not to employ. In California, Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, and a half-dozen other companies are lobbying to defang a court ruling that could make it difficult to avoid reclassifying such workers as employees. And in Washington, the Republican-dominated National Labor Relations Board has made moves to undo an Obama-era precedent that could make big employers legally liable for contract workers even if they have only indirect control over them.

The GOP takeover in Washington is one reason the Temporary Workers of America, a union of bug testers for Microsoft Corp., gave up on what had been, for people in the software world, an almost unheard of unionization victory, says the group’s founder, Philippe Boucher. The 38-person union successfully organized in 2014, winning the right to negotiate with temp agency Lionbridge Technologies Inc., which provides marketing, testing, and language services. Within a few years, however, Lionbridge had eliminated all their jobs, and the workers say a union-busting complaint they filed in December 2016 with the NLRB against Microsoft dragged on too long. They agreed to settle this spring to get financial relief.

NLRB filings obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests illustrate a broader philosophical dispute about what tech giants owe their subcontracted staff—one that, given the recent settlement, won’t get a day in court. Even though the labor board sided with the union in a preliminary showdown, subpoenaing documents Microsoft and Lionbridge had sought to withhold, Boucher says that years into the process, the message was clear. “It was just meeting after meeting,” he says, “and not going anywhere.” A Microsoft spokesman says, “This was a matter between Lionbridge and its employees, and we are pleased they reached an agreement on the issue.” Lionbridge and the NLRB declined to comment for this story.

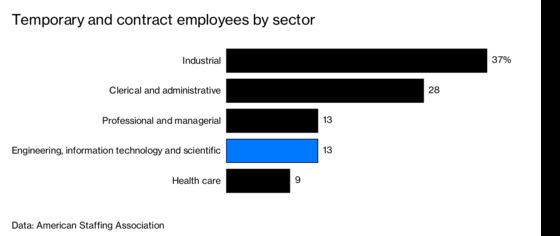

Boucher and his ex-colleagues are among a growing population of tech workers, including many Uber drivers, Amazon.com warehouse loaders, and Google software engineers, who lack the rights and perks of those companies’ full-fledged employees. Of the more than 15 million temporary and contract employees provided each year by staffing companies, about 2 million are in engineering, infotech, and scientific sectors, and roughly the same number serve in professional and managerial jobs, according to estimates from the American Staffing Association. Google parent Alphabet Inc. now has fewer direct employees than it does contract workers, some of whom write code and test self-driving cars.

“Companies are deciding they don’t want to make long-term commitments to people, and they’re using a variety of devices to shift that work out,” says David Weil, dean of Brandeis University’s social policy and management school who oversaw federal wage-and-hour enforcement during the Obama presidency.

Four years ago, Boucher says, he hoped to force Microsoft to improve working conditions for the Lionbridge temps, who were testing apps at a Microsoft office in Washington state. In 2015, after the union was formed, Microsoft began requiring Lionbridge and other contractors to provide workers with at least three weeks of annual paid time off. But the union’s negotiations with Lionbridge broke down, and in 2016 the contractor told Boucher and his colleagues it planned to lay off some of them in response to reduced demand from Microsoft. After making concessions to secure a contract that would at least offer severance pay, the union members learned the layoffs would actually include all of them. In the December 2016 filing with the NLRB, Boucher alleged that the mass termination constituted illegal retaliation for union activism and that under the Obama policy, Microsoft should be considered a “joint employer” liable for that wrongdoing.

Throughout the proceedings, Microsoft maintained it had no involvement in the decision, and that it could be explained innocently enough. The number of apps in its Windows Store had dwindled to 13 percent of the 1.1 million offered in 2014, the company said, and it needed less bug testing from Lionbridge, according to a January 2017 memo obtained via a FOIA request. It told the NLRB it was “entirely unaware of the basic details of the alleged layoff” and that entertaining the union’s effort to “manipulate and abuse the Board process by enmeshing an uninvolved company … encourages the Union and others to drag Microsoft and other large companies into labor disputes for which they do not have involvement or responsibility.”

In documents obtained via FOIA request, the union provided updates from management in the fall of 2016 about pending assignments that it said showed no substantial decline in workload. To help demonstrate that Microsoft was a joint employer, the union provided documents such as an email appearing to show a Lionbridge manager sharing performance metrics with Microsoft counterparts and a list of Microsoft managers who worked in the same office and oversaw Lionbridge employees’ work—at least one of whom listed his management of contractors on his LinkedIn résumé. In April 2017, NLRB investigators ordered Microsoft to turn over more documents in the case, including those dealing with the shutdown of the unionized office and training or setting rules for Lionbridge contractors. A year later the board ruled against the companies’ motion to throw out that order.

By then, however, the subpoenas were moot. The union was already finalizing a settlement with Lionbridge to resolve the case by withdrawing the NLRB allegations. Boucher says the victory on the subpoena was little comfort to dismissed staff who needed money.

Boucher, a 68-year-old French immigrant who spent decades as an anti-tobacco advocate in Europe, now says tactics such as shareholder activism may hold more hope for improving how companies like Microsoft treat contractors than trying to unionize under U.S. laws. He’s been trying to get local clergy or activist tech workers at other companies to help him engage Microsoft shareholders about the company’s paid leave policies, but with little success. Still, he says, pressuring the big tech company seems more effective than arguing with the contractor. Lionbridge managers “were consistent from the start,” says Boucher. “They said, ‘Even if you had a union, we are not obliged to give you anything.’ And that’s the reality.”

Eidelson covers labor issues for Bloomberg News. Kanu is a legal editor for Bloomberg BNA.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.