This Tiny Canadian Peninsula Wants to Be the Next Burgundy

This Tiny Canadian Peninsula Wants to Be the Next Burgundy

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Astrid Young set forth from California’s sun-soaked Napa Valley 15 years ago to further a career in wine, she knew she wanted to specialize in pinot noir and chardonnay.

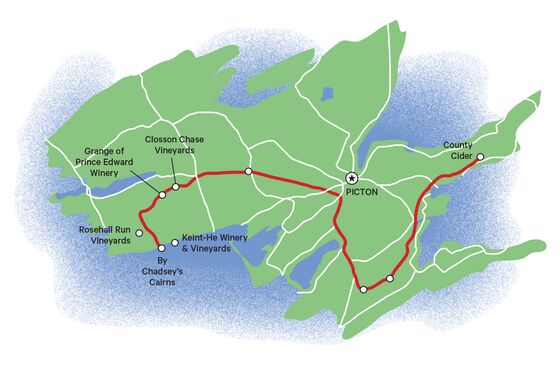

She could have pursued that ambition in the legendary chalk-strewn soils of Burgundy and Champagne, or even in New Zealand’s Marlborough region. Instead, she landed in Canada’s Prince Edward County, then a little-known peninsula in Lake Ontario about 125 miles east of Toronto. “It was this big block of limestone, and I knew it had huge potential,” says Young, now the wine director atMerrill House, a hotel in the region.

At the time, the county had a mere four vineyards overlooking the lake. Since then, more than 40 producers have set up shop in a bid to create a global benchmark for pinot noir and chardonnay. Their efforts have transformed Prince Edward County from a sleepy getaway for suburban dwellers into an emerging powerhouse of viticulture and gastronomy.

Internationally, Canada’s wine is mostly associated with the Okanagan Valley, a temperate parcel in British Columbia that produces big reds from bold grapes such as syrah. But part of Prince Edward County’s appeal is that the area has a similar terroir to Burgundy, home to some of the most expensive and most sought-after pinot noirs on Earth.

But even at the high end, the region’s pinot noirs—which some claim already rival France’s best grand crus—are still a steal in a fine-wine market that charges exceptionally high prices for the varietal. Exultet Estates, a remote producer set on 10 acres of vines planted near the lake, charges C$65 ($50) for a bottle of the Beloved, a vibrant wine with notes of oak and dark fruits. The 2011 vintage is rated a 94 out of 100 by critic Natalie MacLean, whose eponymous website is Canada’s largest online wine-reviewing community.

It’s just as good as a $150 bottle from Burgundy’s acclaimed commune of Volnay, at least according to Exultet Estates owner Gerry Spinosa. “It’s the real deal. It really kicks ass and is worthy of attention,” says Spinosa, a former medical research scientist at the University of Toronto. “It’s a Cadillac for pinot noirs, and if you’re looking at cool-climate expressions, this takes the cake.”

Like Burgundy, Prince Edward County is prized for its limestone bedrock, which lends a succulent and minerally taste to pinot noirs and chardonnays, and its climate, where the warm summer temperatures slowly taper off into autumn, producing wines with strong acidity without being sickly sweet.

But making outstanding wines in this region can be a costly, burdensome process. The frost that periodically afflicts the vineyards of Burgundy and Champagne in the winter can be managed by lighting small fires to warm the grape buds, but the Canadian way isn’t as cozy. Here, temperatures can plummet to –20F. In autumn, workers bury almost all the vines until spring to prevent them from freezing, a practice pursued in only a handful of regions, such as China and upstate New York.

The process of removing the dirt mounds, called dehilling, starts late enough in the spring that the threat of frost has passed. At that point, the vines are so vulnerable, having cooked beneath the soil as temperatures have risen, that even a light graze can damage new buds enough to knock off a cluster’s worth of grapes.

“This is the worst place ever to grow grapes,” says Lee Baker, a winemaker at Keint-He Winery & Vineyards on Loyalist Parkway, a lakeside road deep in the county. “You’re running a higher budget than you normally would anywhere else, because your labor is so much greater.” The burial process requires wineries to hire more workers than vineyards of a similar size elsewhere. “But qualitywise, it’s one of the best,” he says. “It’s not that hard to make a brilliant wine out of these grapes, as long as you get them in here and they’re sound.”

The winery of Keint-He, which is named after the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, was partly funded by former Bank of Montreal Vice Chairman Ron Rogers. It’s home to Prince Edward County’s oldest pinot noir plantings—some of them a ripe old 29 years of age. They’re attributed to Geoff Heinricks, a local winemaker and author of A Fool and Forty Acres: Conjuring a Vineyard Three Thousand Miles From Burgundy. After extensive soil studies, he wrote that the county’s “great dirt”—a cocktail of gravel, limestone, and granite—was perfectly suited to the varietal. And as temperatures have warmed over the past decades, the region’s microclimate is deemed perfect for pinot noir and chardonnay plantings.

The increased attention to the wines is attracting more tourists to Prince Edward County (population 24,735), which, prior to the vines being planted, hadn’t changed much for centuries. The county was created by Upper Canada’s founding Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe in the 18th century. United Empire Loyalist flags—which were flown by the soldiers loyal to the British crown who left America following the Revolution in 1776—still fly outside the Victorian houses that dot the landscape of spruces and firs.

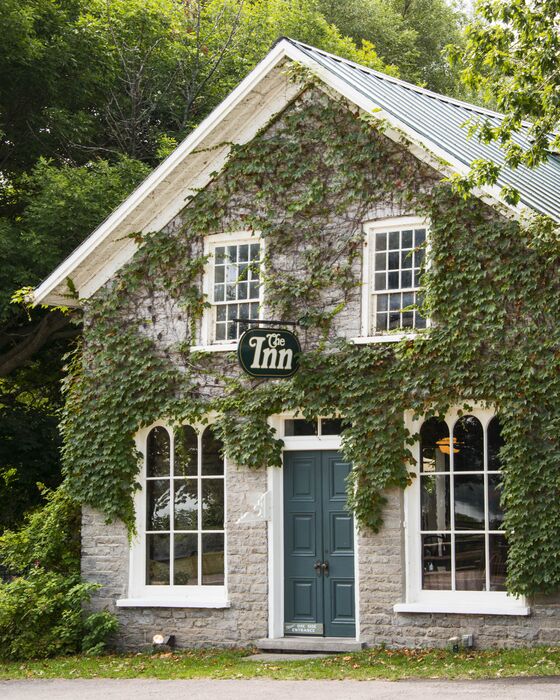

Today the growing numbers of weekenders from Toronto and Montreal have spurred local press to label the bucolic region “the Hamptons of Canada,” but the crowd isn’t as high-profile. (For that mansion vibe, hop a float plane 140 miles northwest to Muskoka.) Attractions lean more toward artisan cafes than designer stores, and low-key outdoor inns serving local beers and ciders with views over the lake rather than corporate benefits and cocktail bars.

To keep up with demand from tourists and local restaurants, Keint-He has increased production to about 5,000 cases a year, up from 800 cases five years ago, says Bryan Rogers, the estate’s general manager. It has about 37 acres planted, up from 23 acres over the same period.

“People are coming here for that farm-to-table offer—great food, great wine, great scenery,” says Emily Cowan, executive director of the Prince Edward County Chamber of Tourism and Commerce. The exact number is difficult for the chamber to track; one barometer is the number of people visiting Sandbanks Provincial Park, a string of golden dunes stretching along the lake. Last year about 750,000 people visited the park, compared with 550,000 three years ago, says Robin Reilly, the park superintendent.

That surge is creating opportunities for hotel owners. In Wellington, the town closest to some of the best vineyards, rates at the Drake Devonshire Inn start at C$389 a night. The hotel underwent an extensive renovation shortly after the owners of the Toronto-based Drake Hotel bought it in 2012. The result is a yuppie paradise complete with outdoor yoga classes, pingpong tables, and a sculpture garden.

In Picton, the county’s historic community, 26-year-old entrepreneur Jordan Martin purchased the Merrill Inn, a gabled manor house with 13 bedrooms on Main Street. He rebranded it Merrill House and brought in art on consignment, including a series of angular, modernist portraits from local gallery Maison Depoivre. Chef Michael Sullivan has introduced six-course tasting menus, serving a wagyu strip steak, tea quail eggs, and Raspberry Point oysters, which Young pairs with Prince Edward County wines.

The restaurant will be remodeled to make room for a temperature-controlled cellar that, once completed at the end of February, can house about 5,000 bottles. (Eventually it may hold double that amount.) Half of the bottles will be from county producers. “With this influx of tourism, it’s reasonable that an old country inn might become a boutique luxury hotel with a standard of dining and service that can rival any five-star hotel in the world,” says Martin, who grew up in nearby Belleville and consulted for the hotel company Jumeirah Group LLC in Dubai.

He’d previously searched for properties associated with wine tourism in Burgundy but found the challenge of helping develop Prince Edward County’s reputation too enticing. “In Burgundy, I don’t think one can be surrounded by this rapid growth and young ambitious people willing to try out new things. There really isn’t nearly the potential for what I’m doing,” he says.

The county’s municipal rules stipulate that a winery can’t be built too close to existing agricultural businesses, which should prevent the local industry from becoming too commercial, Young says. That suits residents fine. As the county’s appeal soars, the region wants to retain the charm that attracted pioneers to its shores in the first place. Earlier this year a real estate agent representing a consortium of investors sat on a bench outside Exultet Estates winery for two days in a row in an attempt to buy the property. “Couldn’t get rid of him,” owner Spinosa says. “He said, ‘Name your price.’ And I said, ‘You don’t even know what we’re doing here.’ ”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Justin Ocean at jocean1@bloomberg.net, James Gaddy

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.