Why Two Years of Historic Wildfires Haven’t Made Southern California Safer

Why Two Years of Historic Wildfires Haven’t Made Southern California Safer

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- To understand what drives America’s increasingly severe wildfire problem, watch what happens after a blaze—and what doesn’t.

In the wake of last year’s widespread fires in California, the state found $300 million to pay for helicopters, increased staffing at its emergency command centers, and established a task force on forest management. What the state didn’t do enough of, fire safety experts warn, is push through the sort of change that matters most: fewer ill-protected homes at the edge of the forest.

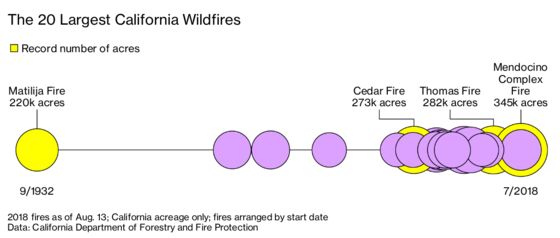

Nobody disputes the need for new ideas. In California, wildfire records are falling at an ever-quickening pace. The 1932 Matilija Fire held the title of the state’s largest for 71 years, toppled only by the 2003 Cedar Fire, which remained the biggest for 14 years. Last December’s Thomas Fire surpassed the Cedar, burning an area almost as large as Los Angeles; that record lasted just eight months, until the Ranch Fire, a part of the Mendocino Complex Fire, overtook it on Aug. 12. And there are still months to go before the end of the fire season—if that term means anything anymore.

This second straight year of historic California wildfires has brought a mix of hand-wringing about the pace of climate change and arguments over who should pay for damages. But the people whose job it is to think about how to minimize the number of lives lost and homes destroyed by wildfires say officials have been slow to adopt meaningful reform. “Our fear is it’s going to take thousands of people dying,” says Michele Steinberg, who is in charge of wildfire safety for the National Fire Prevention Association. “And that’s not beyond the realm of imagination at this point.”

State and local governments may not be able to reverse the rising temperatures and prolonged droughts that spur wildfires. But according to Steinberg and others, there are changes that can help—including applying tougher building codes to more new homes, retrofitting old ones, more aggressive landscape rules, less development in the most vulnerable areas, and letting insurers charge premiums that reflect the risk of wildfire. Those reforms, however, remain anathema in a state squeezed by rising housing costs and the instinct to help communities rebuild as quickly as possible.

California already has some of the most aggressive building codes in the country: Since 2008 any home built in an area with the highest risk of wildfires must be constructed according to strict fire-retardant standards, according to Stuart Tom, a planning official for the city of Burbank and a board member with the International Code Council, which sets model building codes. Those standards include double-paned windows with tempered glass, fine-grain metallic mesh coverings on attic vents, and roof coverings that leave no room for burning embers to get in.

If local officials want to improve fire protection, Tom says, they have the authority to apply those requirements more widely, beyond just the narrowly defined areas the state has designated as having the highest risk. He says he’s not aware of any local governments that have used that authority.

A tougher issue is what to do about homes that predate the 2008 code. When it comes to wildfires, a building is only as safe as the homes around it: If a house ignites, odds are that the one next door will too, even if it’s built to the new standards. Roy Wright, the former head of risk mitigation for the Federal Emergency Management Agency and now chief executive officer at the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, says governments need to consider how to make older houses less of a risk.

Officials haven’t imposed those requirements, not least because they’re expensive. The federal government already gives out billions of dollars in so-called hazard mitigation grants to protect homes threatened by natural disasters such as flooding, hurricanes, and earthquakes. Wright says those grants could be used to help subsidize fire-related retrofits, but states have yet to start asking for it—perhaps because the problem so far has seemed less pressing than other types of hazards.

Another problem, says Molly Mowery, founder and CEO of Wildfire Planning International, which advises governments on fire policy, is that local governments typically wait until after a wildfire to decide what, where, and how to rebuild, which is the exact moment when emotions are heightened. A better approach, she says, is to establish policies beforehand, when it’s easier to think dispassionately. The trouble is that communities tend not to spend time planning for catastrophe, and few local officials believe their town is next. “They’re often not thinking about the front end of disasters, let alone the back end,” Mowery says.

The question that may be most politically fraught is whether it’s appropriate to keep building in the most fire-prone areas as climate change gets worse. “At some point, you certainly have to consider encouraging people to move,” says R.J. Lehmann, director of insurance policy for the R Street Institute, which advocates market-based solutions for climate change. Yet California’s housing crisis means the state needs more homes, not fewer. So any policy aimed at discouraging homes in the forest should include pushing cities to allow for greater density. “I don’t think zoning is usually thought of as a wildfire issue, but it certainly can be,” he says. “Those two things have to go hand in hand.”

In theory, a market solution would come from the insurance industry. Mark Ghilarducci, director of the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, says that if the state left it up to insurers to determine rates in fire-prone areas, people wouldn’t be able to afford coverage. But Lehmann says California goes too far in the other direction, preventing insurers from raising rates based on projected future losses from worsening wildfires. Nor can insurers take into account the rising costs of reinsurance, another indicator that risks are increasing.

Since last year’s fires, lawmakers have introduced bills to make it harder for insurers to raise rates or cancel coverage for homeowners in high-risk areas. Rex Frazier, president of the Personal Insurance Federation of California, a trade association, says he expects some of those bills to pass. “We get a lot of pressure from people who are worried about the impact of climate change and all sorts of failures to adapt,” he says. “And yet when we try to provide the signals that many clamor for us to provide, then others don’t like how it looks.”

Ghilarducci says the state has done as much as anywhere in the country to cope with climate risks. “There actually has been a lot of money and a lot of effort put forward in trying to manage the threat,” he says. “We have looked at this across the board.” Asked whether it’s appropriate to keep developing fire-prone areas, Ken Pimlott, director of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, chooses his words carefully. “If it’s done the correct way, it can be done,” he says. Pimlott defines that as listening to the advice of fire officials, including their warnings about tightly clustered development, building in green belts, inadequate roads into a community, and meager funds set aside for fighting fires. He adds, however, that local governments often disregard those warnings.

Ghilarducci, asked whether it’s wise to let local officials overrule the recommendations of state fire staff, suggests a deeper sort of change could be coming. “Local governments have built a lot of control and responsibility,” he says. “Some of that may be reevaluated.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net, Matthew Philips

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.