China Startups Struggle to Escape the Shadows of Alibaba and Tencent

n their IPO filings, rising companies are warning investors that the tech giants’ deals can feel like a trap.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- More big Chinese tech companies are going public these days than American ones, thanks to heavy investing by Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. and Tencent Holdings Ltd. But the largesse from the tech giants comes at a price. A review of initial public offering filings by Chinese companies shows that while the startups benefit from the cash and customers Alibaba and Tencent provide, the deals can also feel like a trap. They can give Alibaba and Tencent inordinate voting power through board seats and veto rights; come laden with conflicts of interest over hiring, mergers and acquisitions, and other strategic decisions; and deepen the startups’ dependence on traffic from the larger companies to life-and-death proportions.

Almost two dozen companies have flagged Tencent or Alibaba as risk factors in their IPOs in the past two years. They include Meituan Dianping, the food-delivery giant aiming to collect $6 billion in a Hong Kong IPO, and social-shopping site Pinduoduo Inc., which raised more than $1.6 billion in its July offering in New York. “Failure to maintain our relationship with Tencent could materially and adversely affect our business,” Pinduoduo said in its filing, a warning typical of the genre.

The power of Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu Inc. “to decide which companies succeed or fail in China’s vast consumer and corporate markets has become both outsized and unprecedented,” Henry McVey and Frances Lim of KKR & Co. wrote in a recent investment report. And if anything, the Chinese tech giants’ size doesn’t even begin to indicate the true extent of their influence. In some cases, their cash hoards may matter less than their ability to tilt a given market toward one startup or another through access to their massive audiences.

Alibaba says its investments and partnerships are designed to help companies grow in tandem with its own services. Tencent didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story.

Of course, U.S. tech giants have also been criticized for operating like bullying monopolies. The difference is that Amazon.com, Apple, and Facebook are more likely to buy companies outright and absorb them rather than fund a path to an IPO, so such conflicts are unlikely. There are exceptions. Microsoft Corp. was an earlyish investor in Facebook Inc. and last year invested in Indian e-commerce leader Flipkart, now a Walmart Inc. property. Alphabet Inc.’s venture capital arm, GV (formerly Google Ventures), has invested in more than a dozen pre-IPO startups valued at more than $1 billion each, including Uber Technologies Inc. and Stripe Inc. But while GV says it’s invested in 300 companies, Tencent has invested in 600.

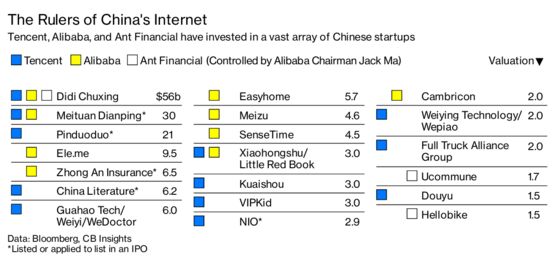

Together, Tencent and Alibaba have given money to 45 percent of the 77 Chinese companies that researcher CB Insights values at $1 billion or more. The two megacompanies, which have a combined $60 billion in cash at their disposal, have used their vast resources to bankroll innovation and champion China’s tech industry. But investors who think backing by those companies automatically signals a quality investment should beware, says Xu Chenggang, an economics professor at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. “With such large sums of cash to deploy, it’s hard to be sure how careful they are with their investments,” Xu says.

Pinduoduo, or PDD, probably wouldn’t exist without Tencent’s ubiquitous messaging platform, WeChat. Tencent’s chat apps helped PDD acquire 344 million customers, who obtain discounts by flagging products to friends on the service. PDD’s July public filing warns investors that its business would take a major hit if cut off from Tencent, which owns 17 percent of the company. “PDD is captive to Tencent, but as long as its business does well, Tencent will continue to support it,” says Brock Silvers, managing director of Kaiyuan Capital. “If PDD falters or something better comes up, though, there’s nothing stopping Tencent from backing another horse.”

PDD spokesman Richard Barton says the company is “confident that investors understand our market position and the strength of our partnerships in the China market.”

When its own leaders disagree with its big backers, a startup tends to compromise. Meituan Dianping counts Tencent as its largest shareholder (with 20 percent, compared with 11 percent owned by Meituan founder Wang Xing), and it uses Tencent’s messaging apps to attract eyeballs for its restaurant-booking, food-delivery, and other services. The company says in its IPO filing that Tencent’s vast user base has helped it grow immensely, but it also warns investors of “limited choices” in cloud and payment providers in China. It says if it can’t maintain its relationship with Tencent, which will provide those essential services through December 2020, its business could be adversely affected. The company declined to comment beyond referring reporters to its public filings.

When China’s second-largest search engine, Sogou Inc., went public last year, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission asked it to disclose more information about its relationship with Tencent. Sogou then warned investors of a potential blow if it lost its perch as the default search engine on WeChat and other Tencent platforms, which deliver 36 percent of Sogou’s traffic. The company said Tencent could choose another provider or create its own search service. Tencent owns 52 percent of the voting power in Sogou and can pull out of an exclusivity agreement in September 2018. Sogou hasn’t publicly announced if the agreement will extend past next month. A spokeswoman says Sogou and Tencent have “deepened their partnership” since the company went public.

China Literature Ltd., Tencent’s e-books spinoff, warned investors at its November IPO that the larger company’s 53 percent control meant “Tencent’s decisions with respect to us or our business may be resolved in ways that favor Tencent” and “may not coincide with our interests and the interests of our other shareholders.” On Aug. 14 investors sent shares in China Literature down 17 percent, the biggest drop since its IPO, after it agreed to buy New Classics Media Corp., another Tencent affiliate, for $2.3 billion. China Literature defended the deal, but analysts questioned its strategic value and high price.

Tencent has pursued IPOs of portfolio companies at a faster pace than Alibaba. That may be because its growth strategy depends on monetizing its 1 billion accounts on WeChat, which doesn’t make money on its own. The tech giant rents eyeballs to other companies, such as PDD or Meituan, in return for advertising and other fees. It’s bought out some companies related to its core business, notably Finnish game developer Supercell Oy, but in most cases it doesn’t want to run all ancillary products and services; it just wants a cut of the money.

By contrast, Alibaba’s e-commerce businesses make money but rely on outside traffic to keep growing. That’s partly why the company is more likely to buy and absorb startups such as Ele.Me, a food-delivery service. Still, a look back at the 2016 IPO prospectus of parcel-delivery provider ZTO Express Cayman Inc. suggests Alibaba’s support looms large. That year, ZTO warned investors that 75 percent of its parcel volume came from Alibaba. ZTO said accommodating many of Alibaba’s partners “may increase the cost of our business, weaken our connection with our end customers, or even be disruptive to our existing business model.” The company declined to comment for this story.

All of this is a reminder of the growing power of China’s tech giants, says Bloomberg Intelligence internet analyst Vey-Sern Ling. “It’s getting impossible to avoid,” he says. —With Lulu Chen and David Ramli

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net, Peter Elstrom

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.