The Unlikely Source of a Healthtech Revolution

The Unlikely Source of a Healthtech Revolution

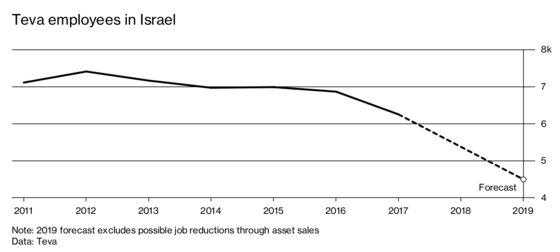

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For decades, Israelis in the prescription drug industry pretty much faced a binary choice: work for Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. or emigrate. So when Teva last year said it planned to cut its domestic workforce by a third as it struggled to pay its debts, those who faced layoffs fretted that their careers were at a dead end.

Instead, Teva’s downsizing has given new vigor to Israel’s life sciences industry. Veterans of the company have launched or joined startups that seek novel ways to discover drugs, develop software to help physicians work more efficiently, or tap technology that lets patients monitor their health. “When I started looking for my next position, it seemed like the pool of relevant companies in Israel wasn’t very big,” says Micah Pearlman, a former strategist for drug launches at Teva, who quit in April and found a job the next month with an artificial intelligence company working in biologic drug development. “It turned out that my initial concerns were misplaced.”

As the world’s largest manufacturer of generic drugs and Israel’s sole Big Pharma outfit, Teva has provided thousands of Israelis with skills needed by the industry. But the drug sector hasn’t had the same effect as tech giants such as Intel Corp. and Check Point Software Technologies Ltd.—or the Israeli military—which have spawned thousands of smaller companies that have supercharged the country’s growth. Less than 1 percent of Israel’s labor force works for pharmaceutical companies, vs. about 5 percent in technology.

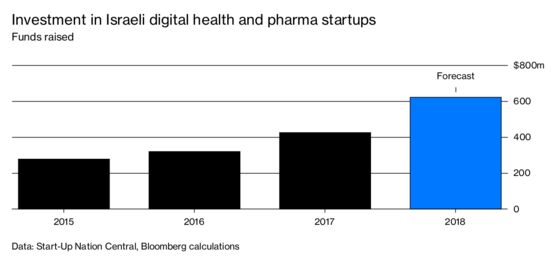

But the draw of the $2 trillion global health-care market is proving hard for tech veterans to ignore. While they used to focus on areas such as cybersecurity and autonomous vehicles, now they’re flocking to medtech companies. Investment in Israeli pharma and digital health startups grew more than 50 percent in the last two years, to $425 million, according to Start-Up Nation Central, a nonprofit that promotes the country’s tech sector. “Tech people are looking to connect with health people,” says Yair Schindel, head of health-care venture capital fund AMoon Partners. “When they meet up with folks that have 10, 15, 20 years of Big Pharma experience with Teva, it’s a serious match.”

Teva has long been Israel’s biggest company by revenue and market value. While it prospered on sales of knockoff drugs, it only recently started focusing on its own branded medications, a business that more closely mirrors the innovation and risk-taking common in startups than the commoditized world of generics. Then in December, with falling profits and debt that exceeds the company’s value, Teva said it would cut a quarter of its global workforce of 56,000, including roughly 2,000 jobs in Israel.

The drugmaker’s woes echo the 1987 shutdown of the Lavi project, an unwieldy state-sponsored attempt to build fighter jets. The program’s demise left thousands of engineers and scientists without jobs. But its failure is widely seen as having been a catalyst for the country’s tech industry, which accounted for almost half of Israel’s $101 billion in exports last year and employs about 200,000 people. Pharmaceutical exports, by contrast, were just $7.5 billion last year, and Teva accounted for well over half of that.

Like many advanced economies, Israel these days is awash in private cash, much of which has been plowed into medical tech startups. Executives at those companies are using the money to hire people with skills gained at Teva: running clinical trials, managing heavily regulated manufacturing processes, or designing commercial strategies for new products. In May a pair of former Teva directors, backed by $60 million from investors, founded 89Bio Ltd., which seeks to develop two early-stage drugs purchased from the pharma giant. Clexio Biosciences, formed in April by several Teva veterans, paid the drugmaker for therapies and technologies aimed at treating illnesses plaguing the central nervous system.

Even some former Teva executives who have emigrated are hedging their bets by allying with entrepreneurs back home. Iris Grossman left in March, after the company shuttered research projects she had overseen, and is moving to Boston, where she’ll be chief scientific officer of a biotechnology startup. At the same time, she and other Teva veterans have launched TheRx Therapeutics, a company in Haifa that seeks to use data mining and AI to speed drug development. The Boston venture helps “provide for my family, but this is a short-term thing and I expect to be back in five or six years,” Grossman says. “The industry in Israel is going in the right direction.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net, David Rocks

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.