Electric Cars Could Be a Job Killer for Japan’s No. 1 Industry

Electric Cars Could Be a Job Killer for Japan’s No. 1 Industry

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Tetsuya Kimura is nervous. The company he runs, which makes engine parts, was already in an endless cycle of cost-cutting to stay competitive. Then last fall the head of his biggest client, Toyota Motor Corp. President Akio Toyoda, began warning that a “once-in-a-century” upheaval threatens the industry’s very survival.

Toyoda wasn’t talking about Donald Trump’s trade war, although that risk looms, too. He was warning about ride-sharing, electric cars, and driverless vehicles, all troubling innovations for anyone whose living depends on the combustion engine. Japan’s government added pressure last month with the announcement that it wants manufacturers to stop building conventional cars by 2050. That’s a distant date, but China, the world’s biggest car market, already has a goal of 1 in 5 vehicles running on batteries by 2025.

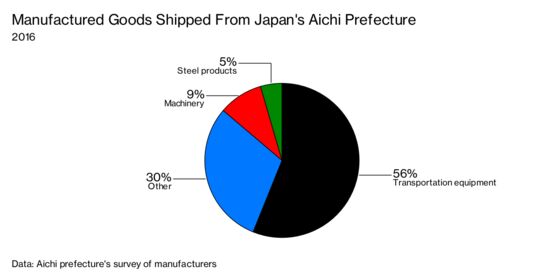

The issue for Japan’s Aichi prefecture, where Toyota and hundreds of suppliers including Kimura’s Asahi Tekko Co. are located, is that electric vehicles use about a third fewer parts than today’s average car. Here’s a sample of what you won’t find in an EV: spark plugs, pistons, camshafts, fuel pumps, injectors, and catalytic converters. For the prefecture’s 310,000 autoworkers, retooling would mean painful downsizing, with far-reaching effects for Japan’s industrial heartland.

“It takes out whole geographical areas,” says Rob Carnell, chief Asia-Pacific economist at ING Bank NV in Singapore. “The hairdressers and the local mom and pop shops, and all of the businesses where the autoworkers would have spent money—they all get hit, too.”

It’s a slow-moving threat. Electric vehicles, or EVs, last year accounted for just 1 percent of global car sales, and most analysts say phasing out gas guzzlers will take many, many years. It’s also true that Toyota’s success with the Prius hybrid has made it slower than other carmakers to go electric, so Aichi prefecture has been able to carry on with business as usual for longer.

In December, though, Toyota announced plans to add more than 10 all-battery models to its lineup starting in the early 2020s. The automaker is also developing a solid-state battery to underpin an even broader EV rollout. Top-tier suppliers Denso Corp. and Aishin Seiki Co., which are part-owned by Toyota and have billions in revenue, are investing to keep up.

“As with all technological change, there’s winners and losers,” says Janet Lewis, an industry analyst in Tokyo at Macquarie. “You’ll have some suppliers that are able to develop some of the key components, but if you’re making mufflers you may not be one of the winners.”

A tour of the factory that Kimura runs in Hekinan, a city that’s an hour-and-a-half drive from Toyota’s headquarters, shows why change can be hard. It’s a relatively big company, with 500 employees, but a visit there is like taking a trip back in time. Asahi has been milling the same engine and transmission parts for decades, and some workers still operate machinery purchased in 1971.

“If you just covered over the computers, you’d think this was the Showa era,” says Kimura, referring to the days of Emperor Hirohito, whose reign ended in 1989.

A 51-year-old former Toyota manager, Kimura started shaking things up at Asahi soon after joining the company five years ago. He added more software and sensors to production lines to cut waste. He also let some people go. But the big innovation was starting a consulting business, iSmart Technologies, to teach other manufacturers how to streamline.

iSmart Technologies’ office is just a short walk away on the other side of the parking lot, but inside it’s a different world. There’s a Silicon Valley-style open-floor plan with exercise equipment in a corner of the room. Several of the venture’s 12 employees were having a meeting while doing pullups and playing around with a balance ball.

Kimura’s goal is to eventually book as much revenue from consulting services as from auto parts. If electric vehicles and ride-sharing really take off, he says, “a lot of our business will disappear.”

Further down the supply chain, where most companies have fewer than 30 employees, there’s less money to invest in new businesses and technologies. In 2017, a year when Toyota made a record profit, 40 percent of Toyota City’s small manufacturers reported falling incomes, according to a local government survey. Only 15 percent said they had any staff doing research and development.

“We don’t have any hands to spare,” says Kunihiko Kondo, who until May was the top official at Toyota City Tekko Kai, a local machinery-makers association.

Even at Jtekt Corp., a giant manufacturer of power steering components and drive shafts part-owned by Toyota, President Tetsuo Agata is uneasy. “We don’t know how we’re going to deal with the new kinds of demand,” he said in a January interview. “Everyone is worried.”

No economist has conducted a formal study of the possible effects of an EV revolution on Aichi. But a recent analysis of Germany’s car industry by the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering showed that, if just a quarter of all vehicles were powered by electric motors, the country would lose 9 percent of its auto jobs. And that was after adding all the employment that EVs would create.

A separate study sponsored by carmakers last year argued that a combustion-engine ban being debated by Germany’s parliament would imperil half of the industry’s workforce. Lawmakers are eyeing a 2030 deadline but haven’t committed.

Martin Schulz, an economist at Tokyo’s Fujitsu Research Institute, says that in Aichi the job losses would be substantial, though probably not as large as the 2017 study suggests. He said auto-parts makers face something like what hit the Swiss watch industry in the 1970s and ’80s, when electronics replaced gears and springs in most wristwatches, putting hundreds of traditional companies out of business and tens of thousands of people out of work.

Which is why, back in Aichi, Kimura is building a new business to replace the old. It’s only a matter of time before Toyota starts ordering fewer of his engine parts. “Whether it’s three years or five years from now, I’m not sure,” he says, “but it’s coming.” —With Jason Clenfield, Elisabeth Behrmann, and Kevin Buckland

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.