Is It Time for Facebook to Consider Hard Limits to Zuckerberg’s Power?

Is It Time for Facebook to Consider Hard Limits to Zuckerberg’s Power?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Editor’s Note: Sometimes the boss can put his company in a tough place. Here’s an overview of the types of key man risk.

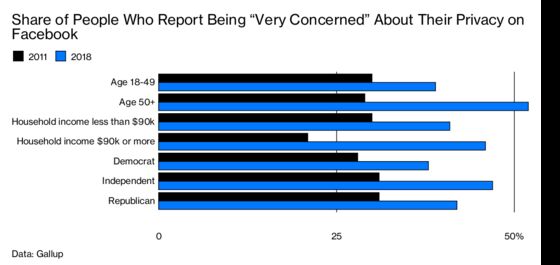

It may seem tough to remember now, but just three months ago, the mood at Facebook Inc.’s headquarters was one of total relief. In mid-April, Mark Zuckerberg, chairman and chief executive officer, successfully parried lawmakers’ complaints during two days of congressional hearings. He’d been made to apologize for allowing Cambridge Analytica, a now shuttered right-leaning political consultant, to access data from Facebook users without their consent. Along the way, he’d suffered small indignities: His notes had been published; the boosterlike cushion he’d sat on had been mocked. But he’d survived.

Employees hoped the political firestorm was over and that users and advertisers would go right back to loving Facebook. When Zuckerberg walked into a staffwide Friday Q&A on April 13, several employees recall, the room exploded in applause.

The celebration may have been premature. On July 26, Facebook’s shares suffered the largest single-day decline of any stock in Wall Street history—losing about $120 billion, one-fifth of the company’s value—after it warned of narrowing margins and slower revenue growth in the coming years. On July 31, Facebook said it had discovered an attempt to spread incendiary political ideas ahead of the U.S. midterm elections, which carried disturbing echoes of Russia’s use of the platform to interfere with the 2016 presidential race. With all this happening, some investors are starting to seriously question an accepted dogma of Silicon Valley: that Mark Zuckerberg is the best person to run Facebook.

In late June, Trillium Asset Management LLC filed a proposal to strip Zuckerberg of his chairmanship. Trillium blames the recent scandals on the board’s inability to check him. Its concerns mirror those laid out in an April note by Brian Wieser, a Pivotal Research Group analyst: “It is difficult to escape the conclusion that there are systematic problems in the way that Facebook has been managed,” Wieser wrote, suggesting there would be “increasing pressure to cause a change in the company’s management structure.”

Inside Facebook, the idea of curbing Zuckerberg’s power would sound nuts. He’s the company’s inventor, largest shareholder, main spokesman, and, because of the way the stock is structured, its sole corporate decision-maker. Workers, many of whom have become extremely wealthy since joining Facebook, tend to look past his failings. That may be why they cheered him after the two days of testimony about their massive data breach—circumstances that would be seen as a crisis at most companies.

For most of its history, this internal halo effect and the dictatorial structure have served Facebook well. Zuckerberg’s biggest bets, especially his $1 billion deal for Instagram in 2011, look downright prescient today. Less successful acquisitions (hello, Oculus) and criticism from media companies had been easy to dismiss as long as Facebook’s user numbers and stock price continued their steady upward march, as they did after the company figured out how to sell mobile ads.

But it seems to have reached an inflection point. Facebook’s 2.2 billion users include two-thirds of all humans with internet connections. Especially in high-value ad markets, it’s a steadily maturing business. Until now, Zuckerberg has made little effort to prepare investors for the bounds of reality.

He’s also struggled to publicly explain Facebook’s policies or its plans for improvement. A week before the bad quarterly report, Zuckerberg sat for a lengthy, generally friendly interview with Kara Swisher of tech news site Recode. Instead of calling attention to the bright spots and laying out his vision, he repeatedly defended the value of permitting views as extreme as Holocaust denial in Facebook’s marketplace of ideas. “I don’t believe that our platform should take that down, because I think there are things that different people get wrong,” he said, referring to posts claiming the murders of 6 million Jews didn’t happen. “I just think, as abhorrent as some of those examples are, I think the reality is also that I get things wrong when I speak publicly. I’m sure you do.”

Godwin’s Law, a tongue-in-cheek assessment of online discourse, states that any prolonged internet debate will eventually lead to somebody comparing somebody else to Hitler. A corollary might be that if your CEO finds himself forced to clarify his philosophical differences with Hitler, as Zuckerberg later did with the statement, “I find Holocaust denial deeply offensive,” you have a management problem. “It means he’s either an idiot or he’s foisting PR blather at people,” says Scott Galloway, an NYU professor and author of The Four: The Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. “Our only hope is that he suddenly realizes he’s not the guy to run Facebook.”

Like most Facebook observers, Galloway recognizes the chance of that is slim. Hoping Zuckerberg turns the CEO role over to a deputy such as Sheryl Sandberg, chief operating officer, or Chris Cox, chief product officer, is “like hoping Mugabe decides he’s the wrong guy to lead Zimbabwe,” Galloway says.

At the Friday employee Q&A after Facebook’s historic market loss, Zuckerberg didn’t dwell on the $120 billion. He said the company’s strategy isn’t swayed by quarterly benchmarks, and he’s confident its current plan is the right one, say people familiar with the matter. Those people say the assembled employees were receptive. Of course, the status quo has worked for them so far. —With Gerrit De Vynck

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net, James Ellis

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.