SpaceX’s Secret Weapon Is Gwynne Shotwell

SpaceX’s Gwynne Shotwell is the secret behind the success stories Musk celebrates.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In early February, Gwynne Shotwell arrived in Saudi Arabia for a bit of last-minute cleanup. SpaceX, the rocket company where Shotwell serves as president and chief operating officer, was days away from its most ambitious launch yet. Its new rocket, Falcon Heavy, would have a larger capacity than any that had lifted off in the U.S. since the Apollo era. And unlike NASA’s Saturn V, which last flew in 1973, the Falcon Heavy would be reusable, capable of bringing its three boosters back from the edge of space and landing them vertically. To make the rocket’s first flight even more memorable, Shotwell’s boss, SpaceX founder and Chief Executive Officer Elon Musk, wanted the experimental payload to include his own sports car.

If all went well, Musk’s cherry-red Tesla Roadster would be propelled toward Mars with a spacesuit-clad dummy behind the wheel and David Bowie’s Life on Mars? playing on the stereo. “Destination is Mars orbit,” Musk tweeted in early December. “Will be in deep space for a billion years or so if it doesn’t blow up on ascent.” News organizations around the world were soon scrambling to cover the launch. “It’s either going to be an exciting success or an exciting failure,” Musk told CBS News on Feb. 5. “One big boom! I’d say tune in.”

But Shotwell wasn’t thrilled about the buzz Musk was generating. SpaceX’s customers pay the company tens of millions of dollars to ferry their $100 million satellites thousands of miles into space. As a general rule, it’s unwise to have them envisioning big booms. And so, with just two days to go before the launch, Shotwell was paying a visit to the Riyadh headquarters of the Arab Satellite Communications Organization (Arabsat), which had reserved a Falcon Heavy launch. “I needed to get way more across than what was in the tweets,” she says.

This was familiar territory for Shotwell. The 54-year-old engineer has worked with Musk since SpaceX’s founding in 2002, longer than almost any executive at any Musk company. She manages about 6,000 SpaceX employees and translates her boss’s far-out ideas into sustainable businesses—whether it means selling customers on a rocket or telling them not to read too much into @elonmusk.

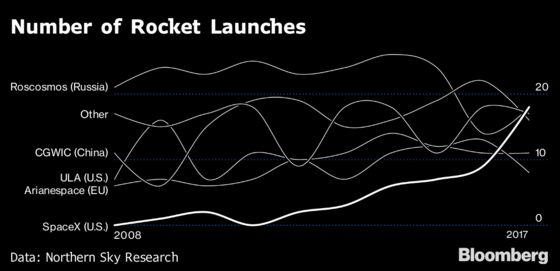

She’s succeeded remarkably. In fact, SpaceX, the business, might be as impressive as SpaceX, the showcase for Muskian wizardry. The company is privately held—Musk owns a majority stake, alongside investors such as Google, Fidelity Investments, and Founders Fund—and doesn’t disclose revenue. But last year its workhorse Falcon 9 rocket reached orbit 18 times, more than any other launch vehicle in the world. SpaceX, which now has more than half of the global launch market, has signaled it would do about 30 launches in 2018, including at least one more Falcon Heavy launch later in the year. The company is worth $28 billion, making it the third most valuable venture-backed startup in the U.S., after Uber Technologies Inc. and Airbnb Inc.

Shotwell has rarely taken credit for any of this. “I try to run the company the way I think Elon would want me to run it,” she says. “He makes great decisions with good data. It’s irritating that he is right as often as he is.” That’s not to say he’s always right. Years earlier, Musk ordered Falcon Heavy canceled, forcing Shotwell, who’d been tipped off by another SpaceX employee, to sprint to a conference room and remind him that the U.S. Air Force, a critical customer, had already purchased a launch.

In Riyadh she told Arabsat that though Musk had evoked the prospect of a fiery failure, he didn’t mean exactly that. “I said, ‘Look, Elon is just trying to set the stage to make sure that people understand that this is a demo flight,’ ” Shotwell says. “We are not going to lift off if we actually think the probability is as bad as 50-50.”

She acknowledged, though, that Falcon Heavy was a new rocket and thus carried some risk. She described the key areas SpaceX was hoping to test—for instance, the separation mechanism that allowed two side boosters to detach from the rocket’s center stage and land. “If this one doesn’t work,” she told them, then the next one would. “We’ve got this.”

After the Feb. 4 meeting in Saudi Arabia she flew to London for a meeting the following day with Inmarsat Plc, Falcon Heavy’s other big customer. Then she boarded a plane to Florida to survey the launch pad at Cape Canaveral, then another to California for the Feb. 6 launch. She arrived at SpaceX’s headquarters in Hawthorne, 15 miles south of downtown Los Angeles, only 40 minutes before scheduled liftoff, settling herself into mission control in a large auditorium separated from the main factory by enormous glass walls.

The launch didn’t go perfectly—the center booster crashed into the Atlantic Ocean and was destroyed—but few of the people watching even realized SpaceX had planned to land it. Most were captivated by the pictures of Musk’s sports car sailing into oblivion, with Bowie blasting and the blue Earth in the background. Then they saw the two side boosters execute a perfectly synchronized landing.

That night, President Trump tweeted a video of the launch with a note of congratulations to Musk. He called Falcon Heavy “American ingenuity at its best.” Musk responded, “An exciting future lies ahead!” Shotwell made no public statement, but in a SpaceX video she could be seen standing up in the control room, pumping her arms. “Gwynne has been able to provide this constant, consistent, positive leadership for SpaceX,” says Lori Garver, a former deputy NASA administrator and the co-founder of the Brooke Owens Fellowship, which supports young women in aerospace careers and counts Shotwell as a mentor. “The public may not be as aware of her, but in the space community she is as big of a rock star as he is. If someone wants a keynote speaker or someone to testify at a congressional hearing, it’s always, ‘Let’s get Gwynne.’ ”

For someone who’s spent much of her career behind the scenes, Shotwell is less restrained in person than one might imagine. She drives a red Tesla with space-themed vanity plates and favors designer boots. During a rare interview with Bloomberg Businessweek in June, she jokes about the flamethrower she shipped to her family’s Texas ranch as a Valentine’s Day gift for her husband, Robert. “We’re going to use that to light our burn piles,” she says, grinning.

The anecdote comes across as strategic, marking Shotwell as no less capable than Musk of a little calculated craziness while also promoting her boss’s work. Her flamethrower was one of 20,000 sold as part of a surreal promotion for Musk’s tunneling side project, the Boring Co.

Shotwell grew up in a small town 40 miles north of Chicago, the middle child of three girls. “This is going to sound terrible,” she says. “I was kind of the boy in the family. I was the hands-on kid.” In grade school, she helped her dad, a neurosurgeon, build the fence around the family’s suburban garden and made a basketball backboard out of plywood. She also fixed her own bicycles.

Shotwell studied mechanical engineering at Northwestern University and took a job in Chrysler Corp.’s management training program. She liked the starting salary but wasn’t crazy about the conservative culture. On the first day of her first rotation, at Chrysler’s mechanic training school, an instructor singled her out for wearing what he deemed a skimpy outfit, then made her stand before the class while he berated her. “I was too young to be offended,” she says. She lasted 18 months and went to grad school.

She moved to L.A. and spent a decade at the Aerospace Corp., a large defense contractor, before going to Microcosm, a private space startup that designs and builds low-cost rockets and rocket parts, for a few years. She was introduced to Musk in 2002 by Hans Koenigsmann, a former Microcosm engineer who’d gone to work at SpaceX. By that time she’d had a taste of the nascent movement of entrepreneurs who were trying to dramatically lower rocket launch costs. But companies like Microcosm subsisted largely on small government contracts, making it hard to try new things (and forcing the small company to waste precious resources dealing with the government-contracting bureaucracy). Private rocket companies, as far as she could tell, essentially had the worst of both worlds.

“The commercial stuff that had gone on was failing,” Shotwell says. What excited her about SpaceX was that Musk, then best known as a co-founder of PayPal, was proposing to sell launch services to private satellite providers for very low prices from the get-go. He wanted to use proven launch technologies and manufacture them as cheaply as possible, eventually reusing rockets to save even more money. Shotwell, who’d recently divorced her first husband and had two young children, knew she was taking a huge risk, but she was charmed by the audacity of Musk’s plan. She signed on as SpaceX’s seventh employee, becoming head of business development. “I thought, Let’s see if I can go sell rockets,” she says.

Not long after starting at SpaceX, Shotwell finagled a meeting for herself and Musk with Peter Teets, director of the National Reconnaissance Office, the U.S. intelligence agency responsible for satellites under President George W. Bush. “He kind of hugged-slash-patted Elon on the back and said, ‘Son, good luck to you, but this is really hard,’ ” she says. “I saw Elon physically respond to that. His resolve firmed up in that moment. Like, ‘I absolutely am going to prove you wrong.’ ” Teets could not be reached for comment.

In recent years, SpaceX has pulled off a number of impressive technical breakthroughs, most importantly landing rockets vertically and then safely using them again. But some key innovations were as much about its business model as its rockets. When Musk founded the company, most other aerospace contractors made money through so-called cost-plus government contracts—that is, the government would come up with a spec and the contractor would meet it, usually with the help of armies of subcontractors and suppliers, then add a fixed percentage fee on top of its total cost. Unable to win (and uninterested in) this kind of business, Musk focused on developing standard products and offering them for as little money as possible. The company’s first rocket, a slender single-engine missile known as Falcon 1, was sold for less than $7 million per launch, a fraction of the price of a ride with the United Launch Alliance (ULA), a joint venture between Lockheed Martin Corp. and Boeing Co. that is now SpaceX’s fiercest competitor.

Musk’s strategy made Shotwell’s job crucial. She had to sell a rocket to satellite companies, even though the rocket had never actually flown, and she had to persuade NASA and the military to fund SpaceX’s demonstration flights. The company’s early customers: the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the U.S. military’s research arm, which paid for its first three launches, and a Malaysian state-owned satellite startup, which paid for a fourth. The final and most important early backer: NASA, which in 2006 awarded SpaceX a $400 million contract to develop a larger rocket, Falcon 9, that would be capable of bringing cargo and people to the International Space Station. “That astonished people,” says Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president for mission assurance and a longtime friend of Shotwell’s. “She was selling stuff to NASA at a time when we had a little rocket on an island. That takes bravery and vision.”

The first and second launches of Falcon 1, in 2006 and 2007, failed. So did the third, in 2008, which went down a few minutes into the launch sequence. The first stage of the rocket normally runs out of fuel and detaches, leaving a second, smaller engine to finish the trip, but after detaching, the first stage kept going and crashed into the second. “It was almost Monty Pythonesque,” Shotwell says. “We rear-ended ourselves.” Musk was devastated, but she spun the launch as a success in conversations with customers. Yes, it had ended in failure, but the only fix Falcon 1 needed to get successfully into orbit—to be shot well, as it were—was to allow a little more time before the stages separated. “When I saw the video, it was like, ‘OK. We can figure it out,’ ” she says.

Amazingly, her assurances worked. The Malaysians didn’t dump SpaceX, though the company did launch a dummy version of the Malaysian satellite before shooting off the real thing. Falcon 1 reached orbit for the first time in September 2008. Three months later, NASA, satisfied with the company’s progress, awarded it a $1.6 billion contract that called for SpaceX to develop a capsule that could dock with the International Space Station. NASA bought 12 missions using Falcon 9 and the new spaceship, Dragon, to take cargo there.

The flights cost NASA about $133 million each, compared with $450 million for a shuttle launch. “The holy grail has always been about lowering the cost to orbit,” says Garver, who was the agency’s deputy administrator from 2009 to 2013. “When it’s so expensive to launch a rocket, you can’t get many things up there. SpaceX has done it, in the face of a lot of opposition.” About the same time SpaceX won the NASA deal, Musk offered Shotwell a promotion, to president and COO. A few months after that, she joined SpaceX's board of directors. “Gwynne is a wonderful person and an outstanding leader,” says Musk. “We would not be where we are today without her.”

Since then, she’s built a reputation with customers and employees for unflappability. Musk is prone to bouts of distress and elation, and he’s renowned for his hair-trigger temper, especially when challenged on technical matters. This was in evidence recently, when he lashed out at a diver who participated in the rescue of a Thai soccer team trapped in a cave. After the diver criticized a minisubmarine Musk had designed and sent to the rescue site, Musk called him a “pedo.” (He later apologized.)

Shotwell eschews Twitter, and aerospace insiders commonly use the word “normal” to describe her, in a barely veiled comparison to her boss. “Gwynne is the steady hand,” says Matthew Desch, the CEO of Iridium Communications Inc., SpaceX’s largest commercial customer. “She’s got the technical savvy, and that underpins her being a great salesperson. But she never tries to oversell, and she’s always open and honest.”

Desch began negotiating with SpaceX in early 2010, as part of a plan to put 75 satellites into space aboard Falcon 9s. The satellites would replace Iridium’s existing array, allowing it to handle broadband communications, and would be financed in part by a $1.8 billion loan. According to Desch, the company’s lenders “liked the price” of Falcon 9—currently $62 million per flight, a little less than half what a ULA launch charges for a flight on its comparable Atlas V. But they were concerned that Falcon 9 had yet to fly. In June, just days after the rocket reached orbit for the first time, Shotwell flew to Paris to make her case before 50 or so skeptical investors at the Four Seasons Hotel. Her presentation included a video of the successful flight. “Gwynne mesmerized the bankers,” says Desch, who closed the deal shortly afterward.

Rocket launches are eerily quiet, at least at first. You see the flash of fire as the engines ignite, but it takes a moment for your eyes and brain to absorb that the thing is actually leaving the pad. It seems impossibly slow at first. By the time the rocket is really moving, the rumble hits your ears. It feels a lot like thunder—distant and then getting closer and closer, until it electrifies your entire body. The rocket hurls itself upward, receding above until it looks like an upside-down matchstick, then it’s gone.

The experience is thrilling if you’re a spectator but downright terrifying if your satellite is on top of the matchstick. “Every launch you go to, you’re worried about it,” says Bryan Hartin, an executive vice president at Iridium. Many in the aerospace industry were initially uncomfortable with SpaceX’s breakthrough addition of a set of four retractable legs to Falcon 9 so it can land vertically and be reused. “I was thinking, I hope the rivets are tight,” Hartin says.

Even so, after SpaceX successfully landed and reused a rocket in 2017, Iridium agreed to a launch on one of the company’s “flight proven” rockets—the aerospace industry equivalent of a “certified preowned vehicle”—because they’re slightly cheaper and, more important, because SpaceX can prep them faster. The concept of reusability, pioneered by SpaceX, has since been embraced by most launch providers, including ULA. Musk has said that next year SpaceX will take advantage of upgrades to Falcon 9, including improvements to the legs and heat shield, to land a booster and launch it again within 24 hours. The idea is to make going to orbit as routine as flying from L.A. to New York.

Even after all this practice, Shotwell still gets nervous before launches. “Candidly, there is a healthy tension,” she says. “Everything has to be right in order for things to be successful. It’s a very unforgiving technology.”

Falcon 9 has suffered two launch failures, most recently in 2016, when a rocket exploded mysteriously on the launch pad, destroying an Israeli satellite that Facebook Inc. had planned to use after SpaceX sent it to orbit. “The Falcon fireball investigation,” as Musk called it, may have led to a public feud between Musk and Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg, who appeared to anger Musk by failing to show an appropriate level of sympathy. Musk grieved openly. “Turning out to be the most difficult and complex failure we have ever had in 14 years,” he tweeted.

The explosion marked a different kind of turning point for Shotwell. In the immediate aftermath, she says, “I ran around the company with a frumpy frowny face.” But she quickly realized that she needed to project confidence. “You forget that people look to you for not only guidance but for inspiration,” she says. “When I walked around with a worried face, it was not helpful to the company.” An investigation ultimately traced the fireball to a faulty fuel tank. SpaceX returned to flight three months later.

“She realized, probably more than anybody else on the team, that people look at us,” says Koenigsmann. “It’s important that you carry yourself with a certain level of confidence.” Over the years, Shotwell has earned a reputation as the person who can translate Musk’s visions into reality. “She’s the bridge between Elon and the staff,” Koenigsmann continues. “Elon says let’s go to Mars and she says, ‘OK, what do we need to actually get to Mars?’ ”

Shotwell’s leadership—less emotional than Musk’s, perhaps a bit more assertive—came to the fore again in January, when a U.S. spy satellite mysteriously disappeared shortly after being launched into orbit by a Falcon 9. With no official explanation forthcoming and speculation mounting that SpaceX had screwed up, it was Shotwell who took the reins. “Falcon 9 did everything correctly,” she said in a statement two days after the launch. The Air Force released a similar statement backing her up. (The Wall Street Journal reported, by way of anonymous sources, that investigators had found a flaw in a piece of equipment the U.S. had purchased from Northrop Grumman Corp. Northrop Grumman didn’t return a request for comment.)

SpaceX is now developing a plan to launch thousands of satellites that would blanket the Earth with internet access and is designing an even larger rocket, which Musk introduced to the world in 2016 as BFR (for “Big Fucking Rocket”). The BFR is designed to take passengers and cargo to Mars, but Musk has said it could be used to replace long-haul air travel—New York-Shanghai in 39 minutes, for instance.

Shotwell has tweaked the F in BFR to “Falcon.” She says that prototype production has already begun at a factory at the Port of Los Angeles. The rockets can’t be built at SpaceX’s main facility in Hawthorne because they’ll be 30 feet in diameter, way too fat for a truck to transport to launches. BFRs will have to travel by boat.

The company plans to begin test flights next year, even though it doesn’t have any customers yet. “We’re working on that,” Shotwell says. Satellite companies and defense contractors will “need to figure out how to fill it up,” she says. “I can help with that.”

In the meantime, she’s focusing most of her attention on the latest upgrades to Falcon 9 and Dragon. The latter is scheduled to carry astronauts to the International Space Station as early as December. SpaceX will share that milestone with Boeing, which has also designed a crew-carrying rocket launch system; this marks the first time NASA astronauts will fly on a private rocket. It’s unclear whether Boeing or SpaceX will get to the station first, but SpaceX seems to be in the lead at the moment. In late July, the Washington Post reported that Boeing and NASA had discovered a fuel leak during a test, potentially delaying Boeing’s launch. Vice President Mike Pence is expected to announce the schedule on Aug. 3.

The four American astronauts who could ride Dragon—Robert Behnken, Eric Boe, Douglas Hurley, and Sunita Williams—have been fixtures in Hawthorne this year, preparing for the mission. Two of them will fly with SpaceX, while the other two will fly with Boeing. Shotwell calls it SpaceX’s “toughest launch.” With humans on board, the stakes will be higher than they’ve ever been.

If it works, though, her job will get easier. “Hopefully the public looks at SpaceX and says, ‘They do what they say they’re going to do.’ Even when it sounds completely insane at the beginning,” she says. “It might take longer. It almost always takes longer. But yeah, we’re doing really cool stuff.” —With Sarah Gardner

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeremy Keehn at jkeehn3@bloomberg.net, Jim Aley

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.