All the Things Satellites Can Now See From Space

All the Things Satellites Can Now See From Space

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Satellites are orbiting in record numbers. These are just some of the companies, government agencies, and NGOs putting them to use.

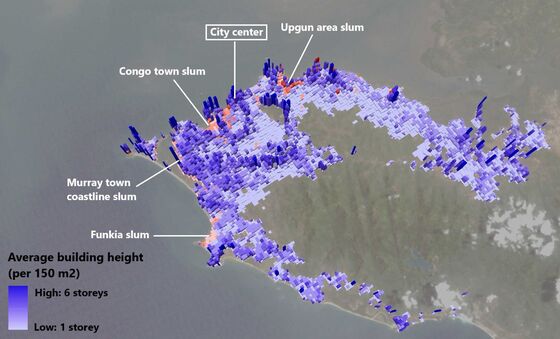

World Bank

● Monitoring high-risk urban development

● Sierra Leone

In 2017 at least 400 people died in Freetown after torrential rains set off a mudslide. Using images from NASA’s Landsat and the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 satellite programs, overlaid with census and other data, World Bank researchers demonstrated how the city’s haphazard development bore some blame for the loss of life.

Almost two-fifths of Freetown’s expansion since 1990, they found, was in areas at medium to high risk of natural disasters, such as on steep hillsides or below sea level, despite laws designed to prevent just that. What’s more, from 1975 to 2015 just 3 percent of the city’s construction was within existing neighborhoods. The farther the city sprawls, the harder it is for public authorities to provide vital infrastructure and services, including sanitation and public transit.

While the World Bank has studied cities’ development since at least 2011, its work on urban fragmentation in Africa started around 2016. “For a while there was a perception within the World Bank that investments in geospatial skills, like remote sensing and satellite imagery, was more of a nice-to-have that didn’t really have widespread utility,” says Megha Mukim, a senior economist at the bank. “Most people now agree that this is a critical decision support capability.”

Researchers with the bank now use satellite data to create policy recommendations for clients such as officials from developing nations and urban planners. They plan to publish their findings on Freetown’s development later this summer. —Andre Tartar

Ursa

● Estimating oil stockpiles

● China

Ursa Space Systems’ main mission is to shine a light on the dark corners of the global supply chain—specifically countries where official statistics are incomplete or untrustworthy. To do so, it buys synthetic-aperture radar imagery of 10,000 oil tanks worldwide, focusing on the heights of the lids to measure fluctuation in the oil levels underneath. Ursa then sharpens the images and feeds all the data into a proprietary machine-learning algorithm. The company has found that the market may be underestimating demand in China, the world’s largest oil importer.

Economic forecasters are major buyers of satellite data. In June, Ursa formed a data-sharing partnership with S&P Global Platts, a provider of commodity indexes and key oil prices. “As satellite data become more prevalent for all industries, market participants will use it to supplement and verify traditional fundamental indicators,” Barclays Plc said in an October report—its first to incorporate satellite data, which was also from Ursa.

The company has rivals. Planet Labs Inc. recently unveiled a platform, Planet Analytics, that customers can use to track planes, ships, roads, buildings, and forests worldwide. Orbital Insight Inc. has its own oil storage tracker and does daily automobile counts for 80 U.S. retailers.

Satellite measurement is by definition far removed from what’s happening on the ground. Given the opaque markets Ursa targets, it has to sell clients on data that are often unverifiable. Co-founder Derek Edinger, who’s helped build satellites for the likes of Raytheon Co. and Lockheed Martin Corp., says the company’s findings go through automated checks and human verification, and its algorithms get better with each image it processes. —Jeff Kearns

EarthCast

● Providing in-flight forecasts to pilots

● Earth’s atmosphere

When one of the more than 10,000 pilots flying for a certain large commercial U.S. airline needs to know whether that dark cloud bank ahead will affect their flight, they can power up an iPad, tap in their flight number, and see a weather forecast tailored for their particular plane. The company behind this application is EarthCast Technologies LP, founded in 2011 by NASA veteran Greg Wilson. (The airline declined to be named.)

Pilots have long had access to basic weather information for their departure and arrival airports, but EarthCast has given them the ability to map out conditions along a particular flight path. The company pulls data from a constellation of 60 mostly government-operated satellites, overlaying that with information from ground- and aircraft-based sensors tracking everything from lightning strikes to turbulence. This fully localized, real-time capability sets EarthCast apart from consumer-facing services such as the National Weather Service and the app Dark Sky; in addition to airlines, EarthCast’s clients include government agencies and other commercial weather companies. In theory, EarthCast could customize forecasts for everything from hot air balloons to drones. —A.T.

World Health Organization

● Refining detection of airborne particulate matter

● India

Carbon dioxide gets all the attention these days—not only because it’s the main driver of climate change but also because its effects are global and long-lasting. Old-fashioned air pollution is a more local affair. Also known as particulate matter, it’s heavier, doesn’t mix as well with air molecules, and succumbs over time to gravity, rain, and other forces that remove it from the atmosphere.

Harvard scientists showed in a landmark 1993 report that particulate matter is “positively associated with death from lung cancer and cardiopulmonary disease.” That finding has since been backed up by numerous studies, generally relying on ground-based pollution sensors. But such systems provide only spotty coverage. In recent years, the World Health Organization has drawn on satellite data to produce its annual State of Global Air report, running the data through an algorithm that divides the atmosphere into a million “boxes,” then calculates how weather moves from box to box, producing a simulation of how air—and pollution—move around the planet.

In the most recent edition, published in April, researchers showed that 95 percent of humanity lives in areas with unhealthy air. The proportion of North America with high levels of the most dangerous fine particulate matter fell from 62 percent from 1998 to 2000 to 19 percent from 2010 to 2012, in no small part due to amendments to the U.S. Clean Air Act passed in 1990. In India the concentration of the same-size particles has jumped almost 20 percent since just 2011. —Eric Roston

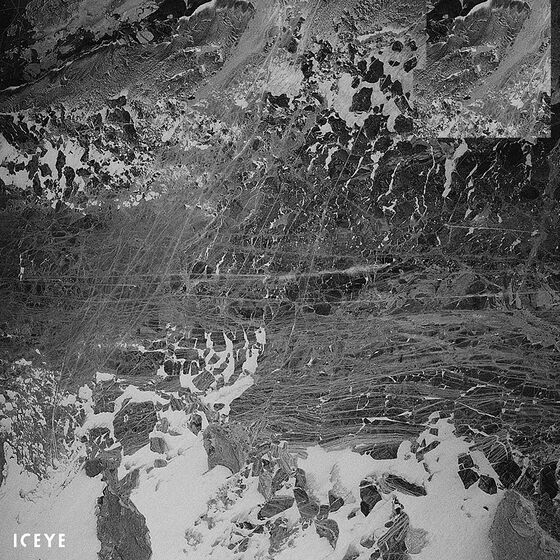

Iceye

● Mapping sea ice

● Arctic Circle

Shipping and oil companies are rushing to exploit Arctic seas newly freed by melting ice caps—but to do so, they need up-to-date information on the location of remaining frozen hazards. The task is well-suited to synthetic-aperture radar, which uses electromagnetic pulses transmitted by satellite-mounted antennae to build detailed three-dimensional images.

SAR satellites used to be two-ton behemoths the size of city buses, so expensive to build and hurl into orbit that they were controlled almost exclusively by governments. Iceye Oy, which started in 2012 as a student project at Aalto University in Finland, set out to upend that model. “We had to rebuild every part of [the SAR satellite] down to the transistors,” says co-founder Rafal Modrzewski.

Iceye’s SAR is 10 times smaller than the standard version and weighs just 80 kilograms (176 pounds). In January the company sent its first SAR microsatellite into orbit. Because of its size, its low-cost construction, and the relative ease in launching it, Iceye’s SAR can provide raw image data at a cost of about $1 per square kilometer, a 10th of most other SAR image providers.

There are a few drawbacks to mini-SAR satellites, including image resolution that’s 10 percent to 20 percent less acute than their full-size cousins’. And their life spans are less than half that of the giant versions, but Modrzewski says you could afford to build 100 mini-SARs for the cost of a single large model.

So far, Iceye’s customers include Exxon Mobil, Sweden’s Saab, the Finnish and U.S. militaries, and Arctia, which operates ice breakers that escort ships through the Arctic. To make its data more readily interpretable, Iceye uses machine learning to detect features such as ice, water, forests, and agricultural cover. It plans to assemble a constellation of 18 satellites that will allow it to capture images of almost any spot on Earth once every three hours. The next launch is planned for October. —Jeremy Kahn

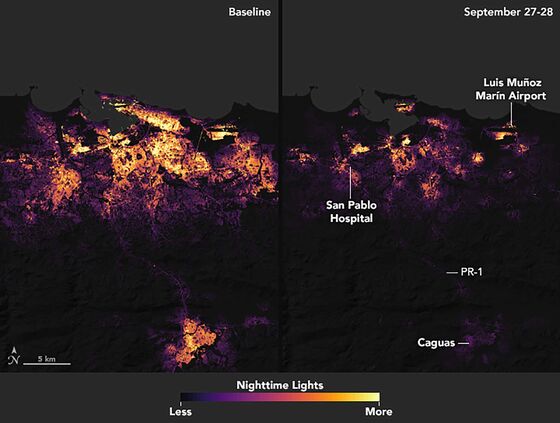

NASA

● Measuring the effects of Hurricane Maria

● Puerto Rico

Since 2011, much of the best nighttime imaging has come from a satellite called Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (NPP), a joint project of NASA and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In the days following Hurricane Maria’s landfall in Puerto Rico last September, a team led by Miguel Román of the NASA Goddard Space Center worked with Suomi NPP images, using software tools to filter out nonelectric light and producing a powerful set of before-and-after images that revealed the devastating extent of power outages and other infrastructure damage.

This analysis was made possible in part by an earlier effort to understand and measure the accuracy of Suomi NPP imagery. Last spring, Román traveled with a team to Puerto Rico, where they pointed LED lamps with predetermined power levels at reflective targets, creating a baseline they could use to quantify errors based on cloud cover and other factors. He calls the trip “a first step to develop a new set of guidelines to assess the quality and stability of nighttime satellite measurements.” A final analysis of Hurricane Maria’s impact using the nighttime lights data is expected later this year. —A.T.

TellusLabs

● Tracking global crops

● Turkey

TellusLabs Inc. is among the companies that rely on their expertise sifting through and enhancing satellite images rather than collecting the images themselves. Co-founded two years ago by a former NASA scientist, the agricultural-data startup relies primarily on NASA and European Space Agency satellites to power prediction models for millions of acres of wheat, rice, and other crops. What these older government satellites lack in precision, they make up for in their ability to measure thermal infrared bands, which show whether something is alive and radiating heat. “The pixels are much larger,” says general manager Fernando Rodriguez-Villa, “but they’re incredibly rich from a spectral perspective.”

Having started out measuring U.S. corn and soybean output, the company is expanding into more categories and countries to serve a multinational client base—including the likes of Unilever Plc. Palm oil, coffee, and cocoa are all growth areas; TellusLabs has detailed predictive models in 10 countries, with crop health statistics in dozens of others. One area of increasing interest is Turkey, where advances such as higher-quality seeds have boosted wheat harvests, but where political uncertainty is seen as a possible obstacle to progress. —A.T.

SpaceKnow

● Counting cars in Six Flags parking lots

● U.S.

San Francisco-based analytics company SpaceKnow Inc. can identify and track everything from planes at John F. Kennedy International Airport to shipping containers in the Port of Hamburg, which it does by tapping data from about 200 public and private satellites.

SpaceKnow prides itself on being a “DIY spatial analytics platform,” says Chief Executive Officer Jeremy Fand. (SpaceKnow provides certain indexes to Bloomberg terminal subscribers; Fand was a senior product manager at Bloomberg LP before moving to SpaceKnow.) Anyone so inclined can go to its website and select a geographic area to zero in on. Those interested in specific companies or industries can order custom reports. “Say I’m a trader who’s responsible for trading Six Flags stock,” Fand says. “I would want to use SpaceKnow analytics to look at all Six Flags parking lots all the time.” Prices start at $10 per square kilometer analyzed and vary depending on the computational and labor demands. If the customer wants exclusive access to the reports, that also adds to the cost.

One area the company’s clients are particularly interested in is infrastructure development—whether there are new mines in the cobalt-rich Democratic Republic of Congo, say, which could indicate an imminent rise in minerals prices or an increase in production of electric car batteries. —A.T.

Imazon

● Policing Amazon deforestation

● Brazil

Ten years ago, Carlos Souza, senior researcher at the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment (Imazon) in Brazil, started using satellite data to develop a picture of Amazon deforestation. The images were relatively low-resolution, so Souza layered in other sources of data to produce a detailed, acre-by-acre portrait of Amazon rainforest cover.

Today, scientists and engineers at the European Space Agency make Souza’s job much easier. One of the agency’s Sentinel satellites provides him with optical and infrared imagery, while another uses radar to cut through cloud cover and fill in any gaps. Imazon can now spot changes in forest cover from one month to the next. “Our goal is to get as close to real-time information about deforestation as possible,” Souza says.

Deforestation spiked in Brazil in 2004, prompting new laws that partially clamped down on the practice. But enforcement is a nagging problem, and in recent years the government has tried to roll back environmental laws. The deforestation rate has stayed steady, but Souza considers that bad news. “We are still losing a lot of forest to illegal deforestation,” he says.

Imazon makes its tree-clearing images available to the public as well as to local law enforcement, and so far that’s led to some raids on illegal sawmills. Souza believes officials can do more. He’s focused on getting data into the hands of local governments through Imazon’s “green municipalities” program, which trains officials to identify deforestation. —Shannon Sims

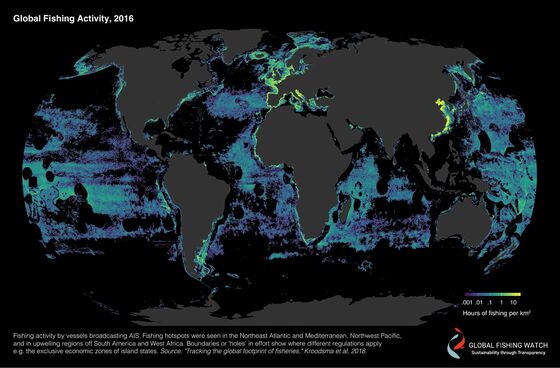

Global Fishing Watch

● Stopping illegal fishing

● Indonesia

The fish-filled waters around the Indonesian archipelago have long been fertile territory for foreign poachers, and until recently they’ve been all but impossible to police. Led by fisheries minister Susi Pudjiastuti, the government made a breakthrough last year when it teamed up with the international nonprofit Global Fishing Watch, which processes satellite-gleaned ship-tracking data to help identify where and when vessels are fishing illegally.

To avoid collisions, ships over a certain size are required to broadcast their location using the automatic identification system (AIS), a GPS-like program that relies on satellites and terrestrial receivers. Global Fishing Watch analyzes those transmissions alongside data from other sources, including infrared imaging and radar, deploying machine learning to determine which vessels are fishing boats.

The group was jointly founded by three separate companies: SkyTruth, which uses satellites to monitor natural resource extraction and promote environmental protection; Oceana, an international ocean conservation organization; and Google, which provides data-analytic muscle. (Bloomberg Philanthropies is a funding partner of Global Fishing Watch.) Indonesia is the first and only government to provide it with additional data from the vessel-monitoring systems used by smaller boats that aren’t required to carry AIS. With this information, Global Fishing Watch can see when these boats rendezvous with cargo ships to transfer their catches rather than return to port, which is often a sign of illegal activity.

The program is part of a crackdown that began in 2014 and delivered swift results for Indonesia: Government revenue from fishing was up 129 percent last year, compared with 2014, according to the ministry. Global Fishing Watch now tracks about 65,000 vessels globally, and while its partnership with Indonesia is still new, the organization expects the aggressive approach to spread. “Within the next decade, we can be tracking the vessels that are responsible for about 75 percent of the world’s catch,” says its chief executive officer, Tony Long. Peru and Costa Rica have committed to join the program. —Karlis Salna and Aaron Clark

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Jeremy Keehn

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.