Turning Around an Old-School Tech Company

Inside Hewlett Packard Enterprise, new CEO Antonio Neri is a bona fide celebrity. Outside, he’s got a lot to prove.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- At his company’s local customer support and research and development center in Bangalore, Antonio Neri got a reception that’s tough to square with the image of Hewlett Packard Enterprise Co. Four thousand employees stood under a tent in India’s sticky, 97-degree March heat to cheer their new chief executive officer, and waited in line for hours to take photos with him 10 at a time. Wearing a traditional yellow garland over his dark suit, Neri set an easy smile on his face. Two hours deep in the receiving line, he made as if to leave to catch a flight, then opted to keep posing instead.

Close to six months after he officially succeeded Meg Whitman as CEO, Neri has received versions of this star treatment at offices throughout Asia, Europe, and elsewhere. The warmth that’s greeted him has been something more than the run-of-the-mill butt-kissing required during a visit from the boss. The crowds seem genuinely convinced when Neri tells them HPE is entering a new era with the tools it needs to succeed, and that they could rise from the call center to the C-suite, like he did. “As an employee of the company for over 20 years, I know every system and every process, which is good and bad,” Neri said at his company’s conference in Las Vegas in June. “But I have a unique opportunity to really transform the company.”

Neri has a lot to prove. The little-known CEO, who took over from one of the most recognizable women in U.S. business, is still largely following her playbook—hawking servers, storage hardware, and networking gear that are no longer essential in the era of cloud computing. Dell Technologies Inc. and the cloud giants (Amazon.com, Microsoft, Google) have sapped HPE’s client base, and they’re working harder to target the clients it has left. HPE has slashed costs and jobs, and is groaning under almost $14 billion of debt.

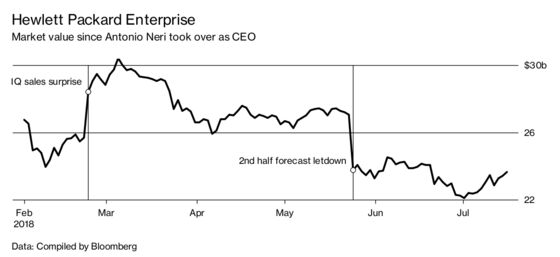

While HPE has made some minor investments and acquisitions during Neri’s first two quarters in charge, its value has fallen about 8 percent, to $24 billion. Sales and profits have risen, and Neri has continued Whitman’s hiked dividends and stock buybacks, but shares plummeted after he said on a May earnings call that investors should expect a “challenging second half.” The company’s bets on future engineering trends are a long way from fruition.

Yet the CEO remains a true believer. At 51, he’s been with the company for 23 years, through strong times, weak times, and devastating, helpless times. “HP never stopped innovating,” he says, even during its 2015 breakup, the biggest in corporate history. Whitman says she’s seen a “continuation” of her work with Neri during his early months in charge. “Antonio will make it his own as he goes on, as he should,” she says. But investors want to know: How long will that take, and will it be enough?

Neri tells anyone who’ll listen that he never expected to become a CEO. The son of an Italian homebuilder, he was born and grew up mostly in Argentina, repairing equipment on a local naval base before going to technical school. He studied drawing and painting for nine years and ultimately got art teaching certifications. “If I had to do my career all over again, I’d be an architect,” he says. He still paints landscapes, boats, and 18th century war scenes in a studio at his vineyard in Livermore, Calif., southeast of San Francisco.

The CEO met his wife, Caroline, in the cubicles of his first HP call center job, in Amsterdam. Despite his taste for fancy shoes and sports cars, Neri has a reputation as an everyman at the company, in part because he’s had almost every job. From customer service, he climbed through the printing unit; ran services for the computer division; headed the services wing; led servers and networking; and took over the rest of the business-focused group before being elevated to president.

Those weren’t great years for HP or its string of outsider CEOs. The board fired Carly Fiorina after poor earnings. Mark Hurd left under pressure after he was caught misstating his expenses amid a sexual harassment claim. (Hurd has denied the claim.) Léo Apotheker was ousted after less than a year, leaving in his wake executive discord and the acquisition of Autonomy Corp., a data analysis company later accused of committing monumental accounting fraud. Whitman tried to clean up the mess by splitting from HP’s consumer divisions and keeping the business-focused stuff for herself. She then spun off HPE’s software and services units but, if anything, hurt the company’s long-term prospects, says Toni Sacconaghi, an analyst at investment manager AllianceBernstein LP. HP Inc., the spun-off business, was expected to struggle after the split but instead became the brighter performer and the world’s largest PC maker.

“The backdrop for HPE is challenging, and they’re a smaller company now,” Sacconaghi says. “In an industry where there isn’t a lot of growth, being big is potentially important.”

Even before he got the top job, Neri says, he’s tried to refocus the company on engineering. In October he gathered HPE’s chief technology officers, some of whom felt they were too siloed churning out short-term products and that HPE lacked technical vision. Neri assured them that engineering, not corporate maneuvering, would drive the company in the future. Since taking over, he’s tripled the internal cash prizes for employees who create patents and communicates with senior engineers at all hours via rapid-fire emails and meetings near his cubicle.

Yet HPE’s problem isn’t, and seldom has been, whether it can improve its products. The bigger issue has been an inability to see the next big thing coming, to feel the tremors under its feet.

Under Whitman, Neri gained credibility within the company for leading the $2.7 billion purchase of Aruba Networks in 2015, shortly before HP split. Aruba, now one of HPE’s fastest-growing divisions, gives the company a rare chance to swipe market share from another incumbent, Cisco Systems Inc. This year, Neri has kept an eye on services and software deals, buying networking startup Plexxi to make its customers’ private clouds in their own data centers work more like the big public clouds. “We need to get three or four of these trends right,” says Vishal Lall, a member of Neri’s inner circle who oversees strategy, investments, and deals. “I think we can get momentum,” he says.

Two of HPE’s principal investments will remain gambles for years. One is memory-driven computing, a pitch for a fridge-size computer that can store and analyze much of what an entire data center does today. The catch is that the idea depends on advances in operating systems, memory, and data transfer technology working in conjunction with new kinds of resistors that don’t yet exist. HPE has spent years working on them, with no end in sight.

The other, Neri’s biggest investment so far ($4 billion over four years), is what’s called the intelligent edge, a catchall term for hardware and software that can analyze data from sensors, cameras, and other internet-connected devices in the field rather than in a data center. This is supposed to speed data analysis and limit the risks of transfer problems or hacking. Neri says intelligent edge products will help add efficiency to hospitals, refineries, and power grids, the kinds of customers HPE has managed to hold on to. Even for wonks, it’s a dry pitch.

And in the next few years, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google are expected to expand aggressively into the areas where HPE and its rivals still hold sway. Researcher Gartner Inc. estimates that the $30 billion market for infrastructure cloud services, a direct competitor to the kinds of services Neri supplies, will reach $83.5 billion by 2021. Sacconaghi, the AllianceBernstein analyst, says it’ll take about that long to determine whether Neri’s turnaround efforts are working.

Neri says he’s determined to create a company “that resonates in the market” and can keep workers happy along with investors. But one of his recent deals illustrates the company’s need to chase sales, and the challenges ahead. In April, he bought IT consulting firm RedPixie, which sells Microsoft Azure cloud services, mostly to banks. Although buyers can also opt to get some HPE hardware as part of a contract with RedPixie, Neri’s company now finds itself in the humbling business of helping customers convert to another company’s cloud services.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net, Emily Biuso

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.