Can the GOP Survive a Trade War?

Can the GOP Survive a Trade War?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On July 6, Donald Trump carried out his vow to slap tariffs on $34 billion worth of Chinese goods, and China immediately reciprocated by penalizing U.S. imports, from soybeans to Teslas. The European Union, Canada, and Mexico also imposed retaliatory levies in response to Trump’s provocations. Four days later, he escalated the feud, threatening tariffs on an additional $200 billion in Chinese products, including auto parts, refrigerators, and electronics, as well as baseball gloves and handbags. The global trade war is on.

Trump says trade wars are “easy to win.” Economists think differently, although most expect the U.S. to emerge without serious damage. A bigger question is: Will Republicans? That will depend on the scale of the conflict and the damage it causes U.S. companies and workers. Early signs are ominous. Trump alarmed GOP lawmakers on July 5 by threatening to impose tariffs on all $500 billion of Chinese goods imported to the U.S. “Members hate what the president is doing,” says a former Republican leadership aide. “None of them thinks this is a good idea.”

Maximalist threats are the foundation of Trump’s approach to governing. He’s betting that when he menaces trade partners around the globe, they’ll be forced to capitulate to his will—and the greater the threat, the larger the eventual foreign concessions will be. “No president before Trump would dare threaten China with half a trillion dollars in tariffs,” says Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist and an early architect of Trump’s “America First” trade policies. “He’s laid his six-guns on the table, and there’s bullets in every chamber.”

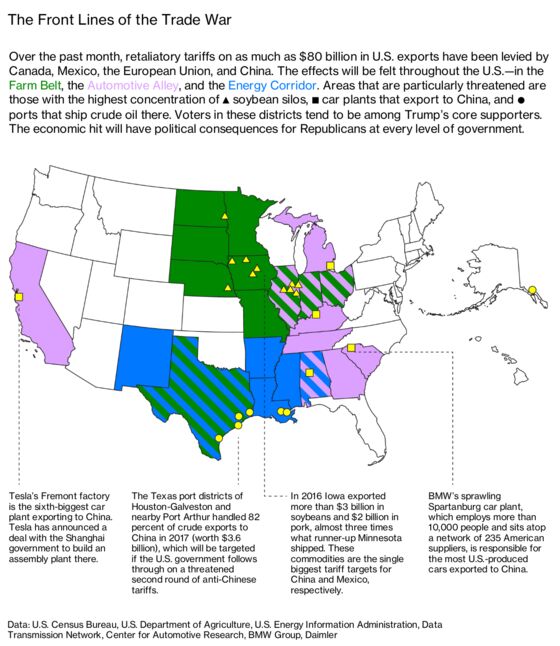

Trump’s decision to start a trade war four months before the midterm elections carries a heavy risk for his party because many of his most loyal followers will bear the brunt of the fallout. This wasn’t the case with his major actions before now. The crackdown on refugees and immigrants didn’t hurt the white, blue-collar voters who make up the core of his support. And although they got little benefit from his tax cut, aimed primarily at corporations and the wealthy, neither were they directly penalized.

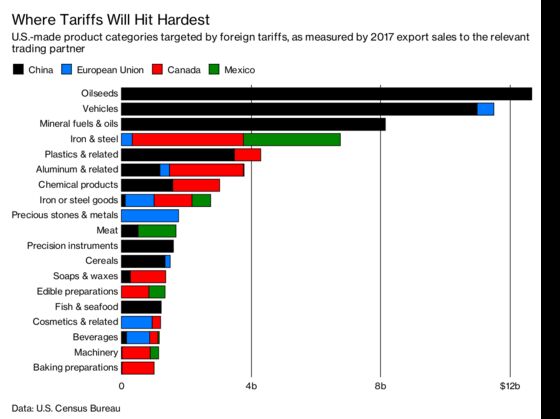

Trade is different. The bulk of punitive tariffs from around the globe falls heavily on Farm Belt and Rust Belt states that went for Trump. Many of the new measures are designed, with almost surgical precision, to harm his supporters. Of the 30 congressional districts hit hardest by Chinese tariffs on U.S. soybeans, 25 are represented by Republicans, five by Democrats—but all 30 voted for Trump.

Canada, Mexico, and the EU have targeted specific Republican politicians, including House Speaker Paul Ryan of Wisconsin and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, by pinpointing items such as cheese, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, and whiskey that are produced in their states and districts. Rank-and-file members and their constituents won’t be spared economic pain either. U.S. Census Bureau data show that the states whose economies are more dependent on exports—and thus most exposed to foreign retaliation—skewed Republican in 2016.

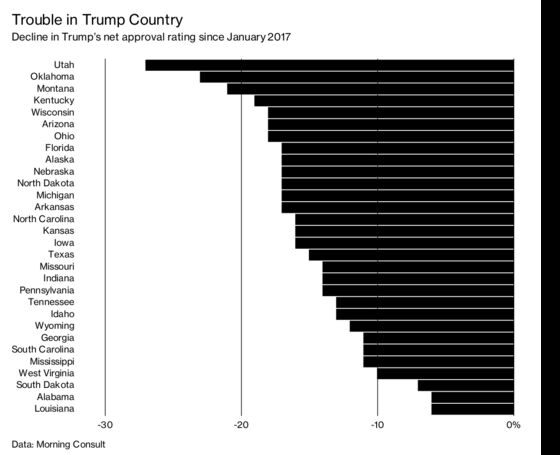

Trump and his party may already be experiencing early tremors. While it doesn’t get much attention, the president’s net approval rating in Morning Consult’s monthly surveys has fallen almost as much in deep-red, agriculture-heavy states such as Kentucky (down 21 percent), Montana (21 percent), and Oklahoma (25 percent), as it has in the bright-blue coastal states of California (15 percent), Rhode Island (21 percent), and Massachusetts (22 percent). “Trump is underperforming in ag states,” says Jennifer Duffy, who tracks Senate and governor races for the nonpartisan Cook Political Report. “In places like North Dakota and Nebraska, which he won by double-digit margin, he’s now barely above 50 percent approval, and in Iowa, which he won by 9 points, he’s well below that, at 44 percent.”

Economists warn that Trump’s trade war will cause prices to rise for U.S. consumers and hurt U.S. companies that import intermediate goods such as semiconductors. But while the macro effect of the new foreign tariffs so far looks to be limited, their impact will be keenly felt by specific industries and businesses around the country, many of them large employers critical to state economies, and as a result will be certain to cause political disruption.

That spells trouble in the Farm Belt, where agricultural staples have been hit by tariffs. U.S. farmers are already dealing with lower prices for corn and wheat. Total farm profits are at their lowest level since 2006, falling from $123 billion in 2013 to less than $60 billion this year as forecast by the government by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Making U.S. agricultural exports less competitive in some of their largest foreign markets will only worsen matters.

Coastal states will also suffer. In Alaska, the world’s top supplier of wild-caught salmon, new Chinese seafood tariffs could cut income for the state’s 16,000 commercial fishermen and harm its largest manufacturing sector, seafood processing. In Maine, those tariffs are costing lobstermen business that’s moving to Canada, while steel tariffs have made their lobster traps more expensive. Florida’s boating industry will be slowed by taxes on motorboats imposed by Canada, the EU, and Mexico.

States with large automotive industries are also in the crosshairs, including a swath of the country from Michigan to Mississippi where foreign carmakers have built some of the biggest plants in the U.S. Many of the vehicles those plants produce are shipped overseas. In Alabama, Daimler AG’s Tuscaloosa plant exports more than 70 percent of the Mercedes-Benz SUVs it produces. Automakers are also major regional employers. South Carolina’s BMW AG plant in Spartanburg, with 10,000 workers, sits atop a sprawling network of 235 American suppliers and is responsible for most of the U.S.-produced cars sent to China.

Kentucky and Tennessee, home to the U.S. whiskey industry, are targeted by the four largest U.S. trading partners: Canada, China, the EU, and Mexico. And along the Gulf Coast, which accounts for 80 percent of U.S. crude exports, tariffs will hit local economies from Gulfport, Miss., to Houston. Since Congress lifted the ban on U.S. oil exports in 2015, foreign demand has helped the domestic oil industry recover from recent low prices. New tariffs could make U.S. crude less competitive and slow the double-digit growth in exports.

The impact of this global retaliation is spread wide enough that even Republicans in safe seats have cause for concern. Not only do Trump’s actions offend GOP lawmakers’ free-market principles, their political costs are also difficult to gauge, because he hasn’t explained when or on what terms he’s willing to bring hostilities to a close.

In the meantime, GOP strategists say they’ll have a harder time beating back Democratic challengers in Senate races in Tennessee, Arizona, and Nevada, where a business-friendly message has long been the basis of Republicans’ appeal. They’ll also have a tougher time knocking off vulnerable Democratic senators in North Dakota, Montana, and Missouri. “The places where members are most concerned are states where it’s effectively a one-industry economy,” says a Republican strategist who requested anonymity to share internal party fears. Trump and some of his top trade advisers are willing to bear these costs, because they believe the showdown will eventually create domestic manufacturing jobs that will benefit the president’s working-class base. But most other Republicans recognize that many of those same workers will be among the first to suffer now that tariffs have started to bite. “It’s stupid policy,” Nebraska Senator Ben Sasse complained publicly in March, “but he has the authority.” Even Trump’s staunchest defenders don’t pretend that U.S. workers won’t get caught in the crossfire. “This is not going to be without some perturbations,” Bannon concedes. “Trump never promised otherwise.” With threats escalating and Trump showing no sign he’ll back down, events could get out of hand. In early July, China’s Ministry of Commerce accused the U.S. of igniting “the largest trade war in economic history.” A March report from Bloomberg Economics estimated that a full-blown trade war, in which the U.S. raises import costs by 10 percent and is met with similar retaliation, would hurt global gross domestic product by $470 billion—roughly the size of Thailand’s economy.

The political fallout would be commensurate. A Peterson Institute for International Economics study found that such a scenario would cause a 2- to 3-percentage-point rise in the U.S. jobless rate, a plunge in asset prices, and disruption of supply chains and productivity. Even actions short of an all-out trade war would create huge disruptions. In a July 2 interview with Fox News, Trump, previewing what he planned to tell foreign leaders at the NATO summit, threatened what he called “the big one”—a global tariff on imported cars and trucks. Last year the U.S. imported $192 billion in vehicles and an additional $143 billion in auto parts. “The imposition of high tariffs on U.S. auto imports would represent an existential threat to Nafta,” Brian Coulton, chief economist at Fitch Ratings Inc., warned in a research note.

Caught between their fear of challenging the president and their desire to protect constituents, Trump supporters in Congress are playing for time. “What I’m saying to constituents is, give President Trump some room,” Republican Representative Steve King, whose Iowa district contains 18,000 soybean farms, told the Washington Post on July 9. “Give him some room to freely negotiate here, and let’s see how it comes out. Don’t undercut the president and take the leverage away.”

But as the impact of retaliatory tariffs grinds its way through local economies in states across the country, it won’t be Trump who has to show up at town hall meetings and answer questions from angry voters. The longer the trade war goes on, the larger the backlash is likely to be. The question that will preoccupy Republican politicians is how long they’ll have to endure it.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Philips at mphilips3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.