China’s Technology Sector Takes On Silicon Valley

Nanjing’s new research park is at the heart of the trade war with the U.S.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- About 300 kilometers (186 miles) up the Yangtze River from Shanghai, the city of Nanjing is developing a research park to foster China’s next generation of technology giants. The zone stretches 216 square kilometers along the city’s north side, housing dozens of high-profile companies as well as a multitude of startups. Across the river is a newer park where roads, sewers, and electrical grids stand ready for even more tech tenants to move in.

Nanjing is on the front line of the government’s effort to compete with Silicon Valley, and the city is playing a brash role in the clash among global trading superpowers. One sunny June morning, a crowd gathers in Building B of the Nanjing park to celebrate the arrival of a startup. “Please put your hands on the screen to officially ignite the opening of our business,” the emcee says to government officials and executives invited onstage. “Three, two, one, ignite!” Simulated lightning shoots up 5 meters from each person’s palm, converging in a phantasmagoria. Music blares.

The startup—Chuangxin Qizhi, or AInnovation—will use government largesse to expand faster than it could on its own. Hocking Xu, an International Business Machines Corp. and SAP veteran who runs AInnovation, is working with companies in retail, manufacturing, and finance to boost operations using artificial intelligence, a priority for the government. “We can move very fast,” Xu says. “We experiment, then change course as needed.”

The growing might of China’s tech sector is at the heart of the trade war with the U.S. Just hours before the Chuangxin Qizhi ceremony, President Trump’s administration released a 35-page report blasting China for “economic aggression” that threatens U.S. technology and intellectual property, taking aim at everything from cyberattacks and theft to government backing for startups such as AInnovation.

Along with tariffs on Chinese goods, the Trump administration is planning tougher scrutiny of Chinese investments in sensitive U.S. industries and technology imports. The measures are aimed at preventing Beijing from achieving its goals of leading the world in fields including AI and electric vehicles.

It may be too late. Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. and Tencent Holdings Ltd. have already climbed into the ranks of the 10 most valuable companies in the world, alongside Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., while a flood of venture capital has fostered billion-dollar startups in China at roughly the same pace as in Silicon Valley. Among the four most valuable startups in the world, three are Chinese, led by payments giant Ant Financial, at $150 billion.

China is pursuing perhaps the most ambitious and unorthodox industrial policy in history. Nanjing alone is spending billions of dollars to move beyond old-school manufacturing. The city of Beijing is building a technology center with $2.1 billion allocated solely for AI research. A total of 156 state-level tech zones scattered across the country are providing similar facilities to support industries deemed national priorities. As part of the central government’s Made in China 2025 economic program, cities, municipalities, and provinces—with support from the central government—offer subsidized rent, tax-free status, and rebates to cover worker salaries.

China still trails the U.S. in key areas, including semiconductors, search engine technology, and social networking. Its technology companies are also far less international than Apple, Google, or Microsoft. But Mike Moritz, a venture capitalist at Sequoia Capital who backed Google and PayPal, argues that China is already surpassing the U.S., in part because its entrepreneurs are hungrier and harder-working. “China is winning the global tech race,” he wrote in a Financial Times column in June. “For Westerners, it should be disconcerting.”

Yasheng Huang, a professor of international management at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, says the country is playing by a different set of rules than the U.S. The American government has legitimate complaints about China’s protectionism and Chinese companies’ attempts to steal trade secrets. But the central lesson from the clash may be that the U.S. needs to learn from China about alternative strategies for development. “I applaud the Chinese government for supporting science and technology,” Huang says. “The U.S. should be doing that, too.”

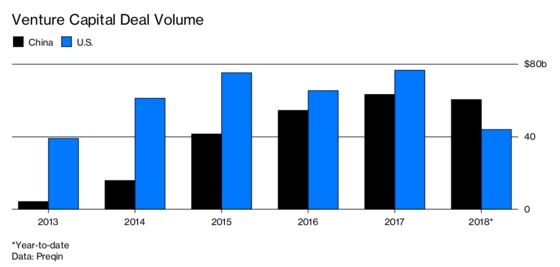

China’s tech industry began with little hint it would threaten American hegemony. The sector emerged with the founding of three internet companies during the dot-com boom of the late 1990s—Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu—modeled on foreign pioneers. But the trio grew into giants and, along the way, proved they could innovate. Out of their success came a slew of startups. As Alibaba prepared for the largest-ever initial public offering in 2014, U.S. and Chinese venture capital firms woke up to the potential of China. The amount of money invested in the country’s startups soared from $4.2 billion in 2013 to $63.1 billion in 2017.

Kai-Fu Lee is one of the pioneers. A Taiwanese national, he began a Beijing venture firm in 2009 after working for Microsoft Corp. and Google. He says the government plays a supporting role in China that’s hard to translate for Westerners used to traditional free markets. One important example, he says, was the official blessing that preceded the surge in startups. In 2014, Premier Li Keqiang gave a speech in which he called for “mass entrepreneurship and mass innovation,” giving explicit approval for people to start companies and make their fortunes. More than 1,200 startups have raised venture money since that speech. The best and the brightest no longer wanted to be Communist Party apparatchiks; they wanted to become Steve Jobs—or Jack Ma, the richest man in China.

“That made a tremendous difference,” says Lee over pizza and beer in Nanjing, where his venture firm and its portfolio companies have set up offices. “It was the mother-in-law effect. Before that, the best job a prospective husband could have was in the government. After that, it was OK for a daughter to marry someone starting their own company.”

The sector has become a key force in the economy. Technology services grew 29 percent in the first quarter, faster than any other sector, as gross domestic product expanded 6.8 percent. The country has gained ground against the U.S. in everything from smartphones and supercomputers to missile technology.

Chinese officials tend to be more forceful in supporting new technologies than their American counterparts—what Lee calls “techno-utilitarianism.” In autonomous driving, for example, U.S. states have shut down experiments after pedestrian fatalities. In a single-party system like China’s, startups can push full speed ahead without losing the support of politicians. “In China, it’s clear you need to keep going because thousands of lives will be saved,” Lee says.

In his forthcoming book, AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order, Lee argues China will catch up to the U.S. in AI. He contends the U.S. holds several advantages, including the best universities and a better ability to draw international talent. But China has equal strengths because of its strong entrepreneurs, capital resources, and government support. He points out that when then-President Obama released his plan for AI in 2016, it had little impact. China published a three-step road map to lead the world in AI by 2030 that was immediately put into action. “The government’s AI plan was like President John F. Kennedy’s landmark speech calling for America to land a man on the moon,” Lee writes.

Behind closed doors, some Chinese business leaders express concern about the government’s stepped-up involvement. Centrally planned efforts in steel and solar fueled similarly ambitious expansion—followed by overcapacity and bankruptcy. “The risk is that money goes to political favorites, then the bad drives out the good,” says Steven Kaplan, a professor of entrepreneurship at the University of Chicago.

Nanjing, a proud city of 8 million, has fallen from prominence in recent years. Although it served twice as China’s capital, it now stands in the shadow of Shanghai and Beijing. It suffered a blow in 2015 when its mayor, Ji Jianye, nicknamed the “Bulldozer,” was convicted of taking $2 million in bribes.

The current mayor, Lan Shaomin, and party chief, Zhang Jinghua, are trying to transcend that legacy, and Made in China 2025 gives them a chance to do just that. They’re clearly in sales mode. “If you come to Nanjing to find a job or create your own startup, you can enjoy favorable policies on talent recruitment, housing, loan-interest deductions, free office space, and so on,” Zhang said during a forum of prospective business clients in April. “If you set up new R&D facilities in Nanjing, we will award you up to 5 million yuan each year. We will give up to 15 million yuan for those who set up angel capital or VC firms. If you invest in Nanjing-based startups, we will reward up to 5 million yuan. If the investment fails, you can get up to 6 million in compensation.”

The city provides tax breaks and incentives to create jobs, not unlike U.S. cities competing for Amazon’s second headquarters. The Nanjing Economic and Technological Development Zone, which has annual tax revenue of 9.5 billion yuan ($1.4 billion), has budgeted 1.9 billion yuan in spending for 2018, including incentives for business, according to government filings.

North of the Yangtze in Nanjing’s Jiangbei New Area, state-backed Tsinghua Unigroup Ltd.’s chip design subsidiary Unisoc has set up a research lab to work on semiconductor technologies, another priority for Beijing. China sees itself as particularly vulnerable in chips, because they’re essential for every kind of computing and the country so far can’t produce competitive products. Chinese smartphone maker ZTE Corp. shut down this year when the U.S. cut off access to American components, including Qualcomm Inc.’s processors. Only an appeal to Trump from President Xi Jinping saved the business.

Yongsan Li moved to Nanjing 18 months ago to open the wireless technology research lab for Unisoc. His team, which started with a staff of 20, now has 120 employees and is projected to expand to 600 in five years. Li says in the second generation of wireless technology, China was 10 years behind, then it closed the gap. Now, as wireless operators move to the fifth generation, China is setting standards alongside the U.S. and South Korea. “We are roughly at the same starting line as the rest of the world,” he says. “That’s the first time in China telecommunications history.”

Li says the progress of Tsinghua and China’s Huawei Technologies Co. means companies such as Qualcomm have to accept lower royalties. He thinks the trade tensions between the U.S. and China stem from shifts in the balance of power. “U.S. companies have fears because Chinese companies are catching up,” he says. Li shows off Unisoc’s offices like a proud father. One wall is covered with plaques for patents. In a nearby room, a half-dozen staffers test the latest 5G designs.

Kaplan, the University of Chicago professor, says China’s government appears to have gotten the big factors right. “The key thing is to let people start businesses and then benefit from starting those businesses,” he says. “They can get rich.” Still, it’s always clear which half of the public-private partnership holds sway. At Building B there was one important absence in the AInnovation ceremony: The mayor of Nanjing couldn’t make it. Once the music died down, the business leaders headed to city hall to get his blessing. —Peter Elstrom and Yuan Gao, with Xiaoqing Pi

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Editorial Board