Did This Jeweler to the Stars Commit the Biggest Bank Fraud in India’s History?

The man who went from being a billionaire jeweller to defrauding billions from banks.

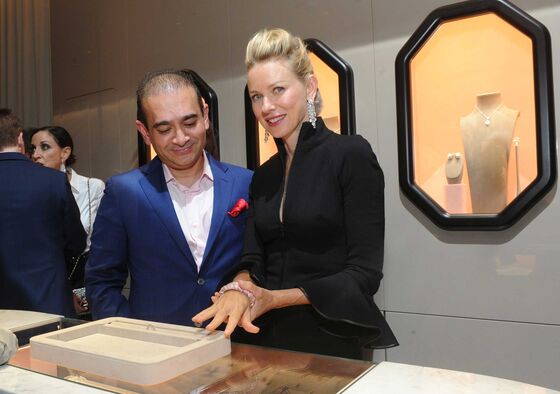

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Nirav Modi didn’t seem like the kind of person who needed to rob $2 billion from a bank. He’s a short man, 47 years old and losing hair, the pocket square in his jacket always arranged to fussy perfection. His daintiness befitted a jeweler to the stars. Kate Winslet wore a Modi bracelet and Modi earrings to the Oscars. Dakota Johnson wore a similar set to the Golden Globes. Priyanka Chopra gazed out of Modi advertisements. Naomi Watts attended the opening, in 2015, of his emporium on Madison Avenue. Christie’s once put his Golconda Lotus necklace on the cover of its catalog and auctioned it for more than $3 million. His stores—in Las Vegas, Macau, Singapore, Beijing, London—were boutiques of bling, where white light bounced off the arrayed gold and diamonds. He told people he wanted 100 shops by 2025. Last year, Forbes estimated his worth at $1.8 billion. A good casting director would have marked him for the role of heistee, not heister.

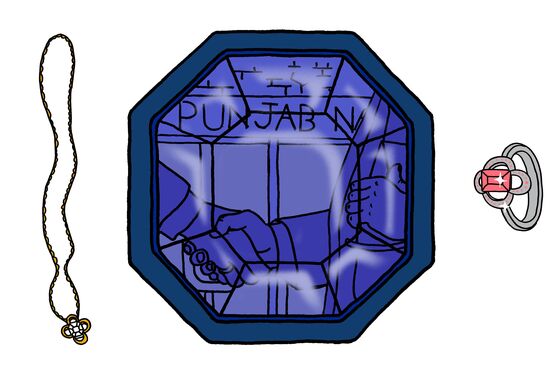

Even the alleged crime, when it finally broke water in February, appeared to swim against the current of Modi’s glamorous life. The money had been taken from Punjab National Bank in 1,213 grinding doses over seven years. It was the biggest bank fraud in India’s history, and it came robed in technical jargon: letters of undertaking and Swift bypasses, margin money and “nostro” accounts, core banking solutions and buyer’s credit facilities.

But these were just details. In conception, the scheme investigators described was classical, old-fashioned; it relied on inside men, and probably on greasing palms, and certainly on dodging technology more than using it. And it depended on the failure of the notoriously creaky structures of governance for India’s 21 state-run banks. These behemoths, which account for two-thirds of the country’s banking assets, are unwieldy and inefficient, vulnerable to heavy hints from corrupt politicians. Their books crawl with nonperforming loans, on which borrowers have stopped paying the interest or principal: $108 billion as of last September. This compelled the government, in October, to announce that it would stuff the banks with $31 billion in fresh capital over the next two years.

Against this backdrop, the con allegedly orchestrated by Modi and an uncle, Mehul Choksi, went off like a Catherine wheel, spraying sparks in every direction. Top-ranking executives have fallen, banking rules have had to be changed, Mumbai’s diamond merchants have noted glumly that credit has become harder to obtain. For regulators, the long and durable life of the swindle has forced two uncomfortable questions into view. How high up in PNB did it go? And what further crises are buried within the untidy ledgers of India’s biggest banks? For everyone else, though, the more intriguing riddle is: How, and why, would Modi have done it?

Modi’s life always had a diamantine glint. He grew up in the Belgian city of Antwerp, the pivot of the world’s diamond trade. His father, his family, their people all bought, cut, and sold diamonds for a living. Over the better part of a century, this community—members of the Jain faith, hailing from Palanpur, a town in the western state of Gujarat—has come to dominate the global industry. Nine of every 10 rough diamonds are worked and polished in Gujarat, and Palanpuri Jain families have long dispatched sons and cousins and nephews to Antwerp to tap trade networks and enlarge their businesses. Modi’s father moved there in the 1960s. At the dinner table, Modi told the luxury magazine #Legend, his family spoke endlessly about diamonds: “It was our way of conversation.”

After he became successful, Modi frequently said he’d really wanted to be an orchestral conductor. Instead, he went to the University of Pennsylvania to study finance, then dropped out to apprentice under Choksi in India, Hong Kong, and Japan—earning, according to one report, the equivalent of $52 a month today. Most Gujarati diamond barons are discreet about their wealth, but Choksi, a round man with a jolly smile, liked to talk about his Ascot Chang suits and his yacht. Years later he would take his company, Gitanjali Gems Ltd., public on the Bombay Stock Exchange, recruiting brand ambassadors from Bollywood and opening posh showrooms.

Neither Modi nor Choksi could be reached for this story, and their lawyers declined requests for comment. But a banker who once counted Modi as a client and knows Mumbai’s diamond business well says Choksi sought to turn Gitanjali into a boutique retail brand, to elevate it above the rote labor of cutting and polishing that his peers undertook. “Nirav also wanted to be very much like that,” the banker says. “He was never called a ‘diamond trader.’ For him, it was always ‘diamantaire.’ ”

In 1999, Modi founded Firestar Diamond Inc., dealing at first in loose diamonds before expanding into the manufacture of jewelry for retailers around the world. But he wasn’t content backstage; he wanted to be out front, bridging the line that divides prosperous customer from opulent product. Eleven years ago, he bought A.Jaffe, the venerable American bridal jewelry brand, for $50 million. Then, in 2010, he created Nirav Modi, an eponymous brand that released limited-edition lines: elastic gold bangles; earrings drizzled with jewels; rings crowned with rare, fat, pink and yellow diamonds; necklaces with names such as Riviere of Perfection and Emerald Waterfall that were made to be murmured by husky-voiced women in advertisements. At least on paper, Modi was the designer of every piece of jewelry sold under the brand. He’d collapsed his empire into his persona.

Two former employees recount the care with which he fashioned his image. The Nirav Modi marketing team was given meticulous notes on the kind of person he was, or wished to be built into. A member of the team kept her notes, three pages of the Modi aesthetic condensed into bullet points: He read Robert Frost and John Keats, Plato and Aristotle; he loved the clean lines of Art Deco, and the music of Nina Simone, and Raphael’s Three Graces, and “butterflies and ladybugs but not necessarily for jewellery.” He went to the ballet and liked any dance, really, that “exudes grace and highlights femininity.” He was “not fond of geometric shapes” and hated “bad craftsmanship in anything—whether furniture or jewellery.”

This employee describes her stint as a strange time and Modi as a polite, persnickety man. During her job interview in his art-filled office, she recalls, he pointed to a poster on the wall—one of the tiny-lettered kind that compress a book’s full text into an image—and asked her if she knew what it was. “He made me get up to go look at it,” she says. When she recognized it as The Count of Monte Cristo, he seemed inordinately impressed. Her workplace held hundreds of people, but she remembers that it was always hushed. Cameras were everywhere—a routine measure, given all the jewelry on the premises, except supervisors used them “to spy on people,” she says. “If you spent too long talking to a colleague, they’d email you a photo of it and tell you off.” Modi wasn’t always in, but when he was, he seemed to follow a finicky schedule: “At a certain time he’d have fruit, and then at a certain time he’d have his green tea in his special flask and cup, and then he’d have lunch even if we were waiting for a meeting with him. He took his own crockery between this office and the other.”

This fastidiousness contrasted with Modi’s verve as a businessman. The other former employee, once a Firestar executive, calls Modi “reckless, a risk-taker.” On the face of it, the gambles paid off. By 2017, Firestar’s revenue had reached $2.3 billion, according to figures filed with India’s Registrar of Companies. Modi’s name was everywhere. He mingled with models and actresses, becoming the kind of lavish sophisticate who flies the Italian chef Massimo Bottura to Mumbai for an invitation-only dinner attended by celebrities. Even so, the fraud accusations came as a shock, the former executive says. “If you’ve taken the country’s money to this extent—well, I can’t digest that at all.”

The stage for the giant swindle was a branch of PNB, set into a jammed road in south Mumbai. On a recent visit, the building, Brady House, was trussed up in scaffolding and green tarpaulin. A lone security guard loitered in the dark corridor leading to the lobby. There were no counters or tellers and probably no cash; Brady House is, as the gilt lettering on a wall proclaimed, a “mid corporate bank,” serving midsize companies. A red sofa, a golden Buddha, cramped plywood cubicles, tacky red linoleum on a flight of steps—the type of lackluster premises that house every state bank branch in the land.

The way Avneesh Nepalia described it, it was sheer carelessness that brought the cat tumbling from the bag. A deputy general manager with PNB in Mumbai, Nepalia registered the first complaint about Modi and Choksi in a two-page letter to India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) in January. Two weeks prior, Nepalia wrote, representatives from three smaller diamond-importing companies owned by Modi had come to Brady House and asked for new letters of undertaking.

A letter of undertaking was a uniquely Indian financial instrument—a relic from the economy’s statist years, when the government controlled the flow of foreign exchange and importers could use only state-owned banks to pay suppliers abroad. India’s central bank recently eliminated them, but they were once a bank’s guarantee for a sum of money in an exchange transaction.

Ordinarily, PNB might have sent a letter in the name of one of Modi’s import companies to the New York branch of another Indian bank, from which Modi’s company was borrowing U.S. dollars to fund American diamond purchases. The second bank would then deposit the money into PNB’s nostro account (a dollar account in a U.S. institution), and PNB would in turn release the money to Modi’s company. PNB repaid the lending bank with interest, in U.S. dollars, while the company repaid the amount to PNB at home, in rupees, adding a low fee for the service. It was a circuitous way to buy and import diamonds, but it would have been more expensive to take out a loan in rupees, convert them into dollars, send them to New York, and pay interest on the principal at home.

On the mid-January day when Modi’s companies applied for new letters, the official in charge asked for collateral, in cash, on the requested amount of foreign currency, usually the standard practice. Modi’s executives demurred—for them, a big mistake. They’d secured many similar letters in the past, they told the bank, without being asked to provide collateral.

Puzzled, bank officials consulted their database. “The branch records did not reveal details of any such facility having been granted,” Nepalia wrote. Then they checked the logs for the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (Swift) system, which held all the transfer and payment instructions transmitted from Brady House to institutions overseas. Nepalia’s complaint is a sober document, betraying no shock at what the bank found—that unapproved letters of undertaking, backing Modi’s and Choksi’s companies in return for little or no collateral, had been issued for years. PNB had been guaranteeing loans without its officers’ knowledge. The first complaint counted about $44 million of credit, issued across eight letters of undertaking.

As its investigation deepened, PNB found more and more letters promising to pay more and more money. It filed another complaint, then another. The smoking hole in the bank’s balance sheet expanded to $2 billion. In the second complaint, Nepalia wrote that when the loans had come due, Modi and Choksi had used some of the money guaranteed by newer letters to pay debts incurred by earlier ones. Arun Jaitley, India’s finance minister, told Parliament in March that at least 1,213 fraudulent letters of undertaking had been issued to Modi’s and Choksi’s companies over the previous seven years. (Modi’s lawyer told Bloomberg News at the time that the allegations were without merit. A PNB communications officer didn’t return phone calls and emails.)

The bank claimed that two rogue Brady House employees, a deputy manager in the foreign exchange department named Gokulnath Shetty and a clerk named Manoj Kharat, had connived with Modi, issuing the letters without asking for collateral or documentation. Then, the bank said, they’d refrained from updating the bank’s database, which would have flagged the credit as unapproved and unsecured. Shetty and Kharat would likely have known—as employees at every state-run bank would have known—that the Swift messaging platform in these institutions wasn’t integrated with customer records and that, as a result, the transfers wouldn’t trigger any warnings. This was the vulnerability that invited the attack.

The caper might have continued, the missing sum growing plumper and plumper, like a snowball rolling downhill, had Shetty not retired in the summer of 2017. When Modi’s companies approached PNB this January for that last batch of letters, Shetty was no longer behind the counter. It was an error, but Modi had loan payments due within weeks, so he might have needed the money.

The CBI hasn’t suggested what Modi and Choksi did with all the money they were accused of pilfering. But Modi had big ambitions. Two people with close knowledge of the process say that, for the better part of last year, he was preparing to take Firestar public. His company had hired two Big Four auditors and a trio of investment banks, and its staff had worked to iron out the various audit irregularities, unrelated to the alleged bank fraud, that had wrinkled its books over the years. “He wanted to grow his business, and to do in five years what might otherwise have taken 20 years,” one of the men says. “If he’d gone public, maybe he could have pledged his equity, raised some money, and finally paid the bank back. Perhaps he would have done that.”

Or perhaps not. Once a man has gotten used to easy money, he often feels entitled to more.

Even as his companies were applying for new letters of undertaking from PNB, Modi may have sensed the end was imminent. According to the Mumbai Mirror, his wife, a U.S. citizen, had pulled their three children out of school the previous year and moved them to New York, telling friends her father was unwell. And the CBI revealed that Modi and Choksi had left India in early January. (Modi’s lawyer said his client had departed for business reasons.)

Once the scandal flared, whispers of their whereabouts began filtering in like rare-bird sightings. They’d flown to Hong Kong, or had winged it to New York, or were roosting in London, the metropolis of choice for absconding Indian billionaires. By the time the government began seizing Modi’s properties—his diamonds, his Porsche Panamera, his Mumbai penthouse, his coastal farmhouse—he’d melted from view.

In early February, his offices were raided by investigating agencies. A few days later, he sent an email from parts unknown to his staff. “The near future seems a little uncertain,” he wrote. His bank accounts all over the world had been frozen. “We shall not be in a position to pay your [salaries], and it would be right on your part to look for other career opportunities,” he wrote. “I hope that we will be able to re-associate ourselves in better days.”

Modi wrote to PNB as well, and the letter leaked into the media. He urged the bank “to be fair” and argued that he ran “a legitimate luxury brand business.” He owed the bank “substantially less” than $2 billion, he claimed, adding that after PNB had filed its first complaint, he’d offered to sell his company to settle up. But the frenzy of publicity and investigation had sparked panic, he scolded the bank, and now he wouldn’t have the necessary capital. “In the anxiety to recover your dues immediately, despite my offer, your actions have destroyed my brand and the business.” (No evidence of such an offer has emerged.)

Early in the investigation, the CBI arrested three men: Shetty, Kharat, and Hemant Bhat, an authorized signatory for Modi’s companies who’d applied for the January letters of undertaking. In its three official complaints, PNB had claimed that Shetty and Kharat were the only bank officers involved, but everyone presumed more would be fingered. Shetty and Kharat weren’t especially influential.

Anil Prabhu, a senior official of PNB’s employee union who knows Kharat well, describes him as “a good boy, a very soft-spoken boy.” Kharat had joined the bank in 2014, starting on a salary of $250 a month. He came from a poor family in Karjat, a town near the city of Pune. “He was always talking about how he wanted to be transferred to Pune,” Prabhu says. “I’d ask him: ‘Stay here a while. Why are you in such a hurry?’ ” Kharat couldn’t have known about the convolutions of the purported scam, Prabhu adds. “His work was like data-entry work. He would have had to type in so many entries, day in and day out,” he says. “It wouldn’t have been easy for anyone to tell which were fraudulent and which weren’t. And Kharat—I can vouch for him. He wouldn’t even recognize what a letter of undertaking is.”

Prabhu was less familiar with Shetty, a clean-shaven man with graying temples. “He wasn’t the type who’d sit and chat with you,” Prabhu says. “He wouldn’t converse at all.” In May the CBI said Shetty had “obtained illegal gratification”—bribes, in other words—from Modi’s and Choksi’s companies in return for his assistance. Press reports claimed Shetty had confessed to the CBI after his arrest, but his lawyer issued a statement denying that he was guilty. Kharat’s lawyer said in a statement that his client had only typed out such letters “under pressure from Gokulnath Shetty. He has no role in the case.” Bhat’s attorney said his client was only a signatory and didn’t understand the terms of the documents.

A former PNB executive, speaking on condition of anonymity, says there was little reason to believe Shetty and Kharat were the only two employees involved. “There is a concurrent auditor sitting there all day, for instance. He’s supposed to validate the daily transactions. It isn’t as if he slipped up on one day, or two days. This went on for years. How did that happen?” The funds moving in and out of PNB’s nostro account overseas should, similarly, have triggered an alarm when they failed to match up with the actual sums the bank had approved.

It’s also possible that Modi’s credit lines simply drowned within PNB’s oceanic volume of business; by 2017 its total assets stood at $106 billion. “At the corporate level, these transactions aren’t noticeable,” the former executive says. “But the branch manager should have noticed.” The governance of India’s state-run banks needs to improve, the former executive acknowledges. Political nudges and corrupt officials are familiar itches in the banking body, so a loose system of accountability is an invitation to fraud.

Harsh Vardhan, the head of Bain & Co.’s financial-services practice in India and a trenchant critic of how state banks are run, says he was stunned when news of the PNB fraud emerged. “I couldn’t understand how this could have happened. This was all Risk Management 101.” State-run banks undergo multiple audits, he says, “all of which seem to have been compromised.”

Cronyism and corruption are endemic to the system, Vardhan adds. Standards change when the borrowers are connected to politicians or bank directors, with loans too liberally advanced and too lethargically pursued. “If you line up a list of the top 20 defaulters, they’re all seen to be politically very powerful,” he says. That’s partly why stressed assets, which include nonperforming assets and restructured loans, make up 16.2 percent of state banks’ loans; the figure for privately owned banks is 4.7 percent. Modi does have powerful friends—he appeared in an official group photo with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi (no relation) at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January—but there’s been no suggestion that political influence helped him and Choksi obtain letters of undertaking.

The notion that they could have pulled off such a swindle with the collusion of just two bank employees was abandoned in mid-May, when the CBI filed charge sheets, running into thousands of pages, against Modi, Choksi, and several past and present PNB employees. The highest official to be named was Usha Ananthasubramanian, the bank’s chief executive officer from 2015 to 2017. Ananthasubramanian and other executives were accused of failing to implement a 2016 order from India’s central bank to seal the gap between PNB’s Swift platform and its main database. Further, the CBI alleged, these officials had misled the central bank, assuring it these systems were secure. (In a text message, Ananthasubramanian denied she was guilty.)

The charge sheets are merely precursors to a trial, but the wheels of the judiciary in India grind with exasperating sloth. Lalit Modi, another tycoon (again, no relation to Nirav) who nipped out of the country just as law enforcement agencies began cracking their fingers, reached London in 2010; the government has yet to submit an extradition request to bring him home for trial.

If Nirav Modi ever makes it back to India, he’ll face multiple charges, including conspiring to defraud PNB and money laundering—accusations his lawyer called “half-baked” in a statement released in May. In a way, the fraud has cost the state-run banking system not only PNB’s immediate $2 billion but also future funds. At least two banks have deferred their plans to raise fresh capital in the first half of this year. “There has been a real shaking of investors’ faith in governance, and that faith was never strong to begin with,” Vardhan says. “That’s where the real damage has been.” The banks can try to convince their shareholders and investors—and perhaps even themselves—that the scam was an anomaly, an aberration, the product of a stray loophole that someone had hoovered money through. Only, there’s nothing as yet to indicate that this is the truth.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeremy Keehn at jkeehn3@bloomberg.net, Max Chafkin

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.