India’s Push to Fast-Track Bankruptcies

Under the new code, cases must be resolved in nine months, instead of the typical four years.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On the third floor of a government complex in New Delhi, the National Company Law Tribunal’s appeals court is crammed with lawyers wearing formal black suits and white neckbands that hark back to the British Raj. Two judges have just been seated by ushers in white-and-gold turbans. The lawyers start arguing. “Everyone knows who his real client is!” yells one, as the crush of surrounding advocates lean in to hear what’s going on.

It might not be immediately apparent, but here in this courtroom, billions of dollars—and the reform record of Prime Minister Narendra Modi—are at stake. On this sweltering afternoon, two of India’s best-known lawyers are arguing over assets belonging to one of many overextended Indian corporations—the bankrupt giant Essar Steel. One bidder is ArcelorMittal, the industry leader, which explains the presence here of Aditya Mittal, son of billionaire steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal. The other bidder is a consortium backed by Russian investment bank VTB Capital, which has offered $5.4 billion. (The amount of ArcelorMittal’s bid hasn’t been disclosed.)

Essar, which owes creditors $7.6 billion, is one of a dozen large debtors that were ordered into bankruptcy court after India’s central bank received additional powers to speed the process of winding down troubled companies. There are more than 2,500 bankruptcy cases wending their way through India’s notoriously slow legal system.

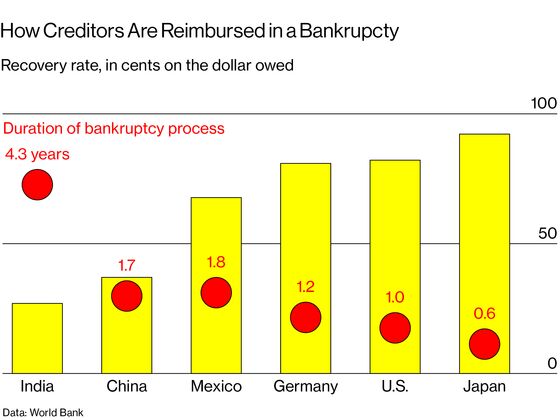

Until the special courts were established by the 2016 Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, bankruptcies could drag on for years. World Bank data show creditors in India recover just 26.4¢ on the dollar, after 4.3 years; in the U.S. it’s 82.1¢ on the dollar, in just one year.

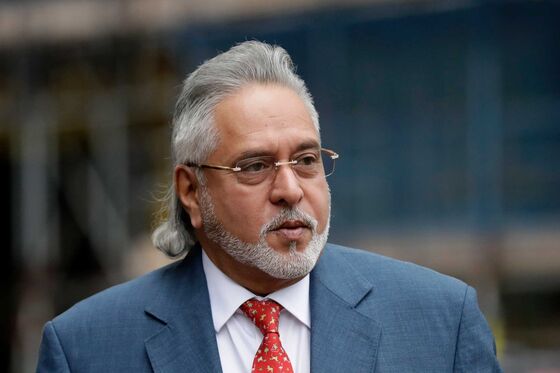

Some founders whose firms failed simply fled India. The most famous of these was Vijay Mallya, the flamboyant “King of Good Times” whose Kingfisher airline collapsed in 2012, leaving $1.4 billion in unpaid debts. The Modi administration is seeking his extradition from the U.K.

Under the new bankruptcy code, cases must be resolved within 270 days—otherwise the firms are pushed into liquidation. The backlog is a symptom of a much deeper problem. India’s banking system is staggering under the weight of $210 billion in bad loans, 90 percent of which are held by state-owned lenders, which has stoked fears the country could succumb to a full-blown financial crisis.

Raghbendra Jha, an economics professor at the Australian National University, says the pile of bad loans is a manifestation of India’s crony capitalism. “You lend to a firm not because it has a high rate of return but because it has the right contacts,” Jha says. “And these things are now being challenged and addressed.”

The Reserve Bank of India has been waging a multiyear campaign to get state lenders to recognize nonperforming loans and has been leaning on bank managers to cut off credit to “willful defaulters”—companies that have stopped servicing their debt even though they have the ability to pay. Modi’s administration also has pledged $33 billion to recapitalize state banks.

The government’s push to speed up the bankruptcy process has another dimension. Authorities are under pressure to help generate jobs for the 12 million young Indians joining the labor force every year. One way of doing that is to quickly find new owners for idle steel plants and other assets, so they can be brought back online.

Of course, this is India, where the implementation of government policy is often chaotic. There aren’t enough bankruptcy courts—only 10 nationwide—or judges to hear all the cases promptly and efficiently. At the appeals tribunal in New Delhi, the top judge has complained he can’t hire support staff because the salaries on offer are too low. The courtrooms are overcrowded, with people spilling out into the hallway and bags of documents littering the floor.

The government has had to amend the law to stop company owners who defaulted on debts from bidding on their own company’s assets in the course of bankruptcy proceedings. In the Essar Steel case, a lawyer representing ArcelorMittal claimed that the VTB Capital-backed consortium was merely a front for the Ruia brothers, a pair of billionaires who control Essar Group, a conglomerate that’s also involved in shipping and oil refining.

More important, some of the cases adjudicated by the tribunals are also getting bogged down in bitter, protracted legal challenges. Tata Steel’s winning $5.1 billion bid for bankrupt Bhushan Steel Ltd. is being disputed by a rival bidder. The appellate tribunal recently put the Essar case on hold until late July, allowing the legal process to continue beyond the 270-day limit that would otherwise trigger a court-mandated liquidation.

Despite the problems, some India-watchers are upbeat about the direction the country is moving in. “India’s new bankruptcy code is now making a significant difference to the speed at which bankruptcy cases are resolved and the amount that creditors are able to recover,” says Shilan Shah, a Singapore-based analyst for research company Capital Economics. “This bodes well for India’s beleaguered banking sector and the economy more generally.”

--With assistance from Upmanyu Trivedi.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.