The Legend of Nintendo

As Nintendo turns 130 years old next year, here’s how it has managed to retain its animated presence.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For anyone who’s ever marveled at Nintendo’s vivid, phantasmagoric, zoologically ornate video games, visiting the company’s understated home in Kyoto, Japan, can be disorienting at first. That such an outpouring of kaleidoscopic products comes from a place so devoid of color can be momentarily hard to fathom. The headquarters are housed in a stark white cubical building surrounded on the perimeter by a sturdy white wall. The lobby is minimally decorated. The sidewalls are sheathed in cool white marble. No Donkey Kong posters. No Mario cutouts. No Pikachu plush toys. The rare sprinkling of color comes from a series of small, framed art pieces: a serene procession of birds and flowers. One Tuesday morning in April, the place gave off the reflective vibe of a monastery or, perhaps, a mental asylum.

On the top floor of the building, Tatsumi Kimishima, Nintendo Co.’s president, took a seat in a wood-paneled conference room, next to a translator. A crescent of handlers settled into chairs nearby while a server brought out cups of hot green tea. She padded quietly about the room, making sure not to obstruct anyone’s line of sight to the president, shuffling sideways here, dipping there, like a spy limboing past a laser-triggered alarm system. Not a drop was spilled.

As the tea was served, Kimishima eased into a laconic summary of Nintendo’s affairs. The past year and a half had been eventful, with the company vaulting back from the brink of irrelevance to reclaim its position atop the global video game industry. Kimishima summed up the triumphant drama with monkish self-restraint: “Certainly, we have been pleased.”

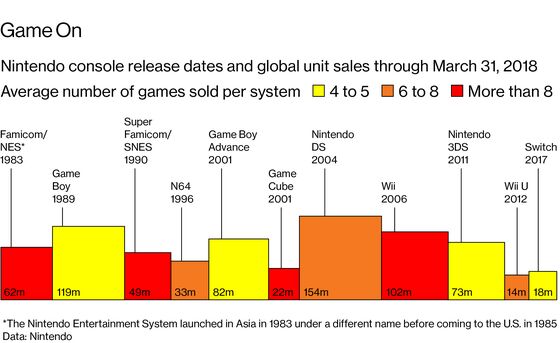

In March 2017, the company released the Nintendo Switch. People were skeptical that the console, which can be used as a portable gaming device or docked to a television set, would succeed. It had been more than a decade since Nintendo’s last hardware megahit, the Wii, and the world of home entertainment had destabilized. Smartphones, some analysts maintained, were the future of video games—not sleek, meticulously crafted $299.99 devices with curious motion-sensitive, detachable controllers.

But from the start, gamers loved the Switch’s originality, versatility, and design. This April, Nintendo announced that during the previous fiscal year it had sold more than 15 million units and more than 63 million games. A strong lineup of reimagined classics had helped drive the frenzy. The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild had sold more than 8 million copies and been named Game of the Year by the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. New iterations of the Mario Kart, Super Mario, and Splatoon franchises had performed similarly well. Nintendo’s revenue had more than doubled from the previous year, to $9.5 billion, and its share price had shot up 81 percent.

With the company once again bear-hugging youthful brainstems around the world, marketers of kid products are rushing to license its characters and start joint ventures. Nintendo is working with Illumination Entertainment, the studio behind Minions and Despicable Me, to develop a feature-length Mario movie. And it’s teaming up with Universal Studios to create theme-park attractions based on Nintendo characters, the first of which will open in Osaka in time for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

In September, the company will start an online service for Switch users, and some feverishly anticipated games are in the works. Investor skepticism that they’ll truly be hits has lately caused shares to dip, but Nintendo projects it will sell upwards of 20 million more Switches and 100 million more games by next April. “We think of the second year and beyond as being especially important,” Kimishima said. “We have to start thinking about how to plan our game releases in order to attract the interest of our audiences worldwide.” In a few months, he would be strategizing at a remove, mentoring a younger apprentice who would take over as president.

As Kimishima spoke, sunlight flooded the conference room. It was a warm spring day in Kyoto. The cherry trees were in full bloom. The subways were clotted with tourists. Elsewhere in Japan, the firefly squid were returning to Toyama Bay. Police in Miyagi prefecture were investigating what had happened to a black-headed gull found wandering around, alive, with a small arrow mysteriously lodged in its skull, as though escaped from a Nintendo game.

Kimishima took a sip of tea. Next year, Nintendo will turn 130 years old. Once again, the outside world is wondering how a company periodically left for dead keeps revitalizing itself. But seesawing is nothing new for Nintendo. It has long alternated between fallow periods, in which the media churns out reports of pending doom, and boom times, during which Nintendo Mania is cast as an unstoppable force. What remains constant is the company’s understated and zealously guarded culture—the system at the root of its unusual ability to recalibrate, with some regularity, to humanity’s ever-evolving sense of play.

Most of Nintendo’s hardware and game builders work alongside one another at its research and development headquarters in Kyoto, a few blocks from its main office. The R&D building is white and minimalist, too. The company is protective of the game makers who labor there, keeping them well out of visitors’ sight. A request to see the cafeteria was politely declined on the grounds that developers might be there, eating. But hints of Nintendo’s creative class were in evidence here and there around the campus. A neon poster beckoned passers-by to attend a concert by the Wind Wakers, a symphony orchestra made up of Nintendo employees. Several times a year they give live performances drawn from the Wagnerian amounts of game melodies written by the company’s composers. The selections vary depending on the season.

Near 1 p.m., the underwater theme from Super Mario Bros. played over the loudspeakers, signaling the end of lunch hour. Shortly after, Shinya Takahashi and Yoshiaki Koizumi emerged from the protected zone and sat down for a joint interview. Takahashi, 54, a top executive and member of the board, is an art school graduate who grew up in Kyoto and emerged in the 1990s as a particularly skillful game producer. He wears horn-rimmed glasses and has the infectiously delighted demeanor of a puppeteer, in contrast to the more painstaking playwright’s bearing of Koizumi, 50, the deputy general manager for the entertainment planning and development division. Among other roles, they oversee the game designers charged with dazzling players on the Switch.

Nintendo’s game creators come from a variety of academic backgrounds. Historically, most were Japanese men, though in recent years the company has hired more women and brought in talent from overseas. The increased diversity helps to replenish Nintendo’s wellspring of creativity, executives say, and ultimately to produce a heterodox array of games that appeal to consumers who aren’t necessarily fervid gamers (read: not just young men).

The expectation is that new hires will learn the craft from senior producers and spend the rest of their careers at Nintendo, continuously honing their command. The setup is reminiscent of the apprenticeship system underpinning the rich, artisanal culture for which Kyoto has long been renowned. In studios throughout the city, apprentices work alongside master craftspeople, producing ceramics, paper fans, tie-dyed prints, cutlery, tea canisters, embroidery, bamboo work, and lacquerware. Kyoto’s artisans pride themselves on never letting their handiwork grow stale; each generation of apprentices is expected to absorb the methods of their predecessors while pushing classical practices forward.

Nintendo’s master artisan, its most revered producer, is Shigeru Miyamoto, 65, who joined the company in 1977 and designed its first globally beloved game, Donkey Kong, a few years later. Miyamoto is still at the company, and all its senior game makers, including Koizumi and Takahashi, have worked extensively at his side. “I’m not young myself,” Koizumi said. “But as a developer working on some of these 30-year franchises, one thing that I do recognize is that just because it’s been around for 30 years doesn’t mean that’s necessarily a strength on its own. What you need are fresh ideas. You need young people with interesting takes.”

The company’s creative methods—and, more precisely, why its best games verge on the sublime—have always been something of a mystery. Over the years, Miyamoto has offered some clues. He’s often told a story about how, when he was young, he discovered a cave in a bamboo forest outside his village of Sonobe, northwest of Kyoto. Initially afraid, he pushed deeper into the subterranean world, marveling at the feelings of mystery and soulfulness that washed over him. That sense of astonishment and animism persisted, helping to inspire hit games such as Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros., and The Legend of Zelda. Miyamoto’s cave tale is to Nintendo acolytes as Plato’s cave allegory is to students of Greek philosophy: a way of framing the inherent challenge of perceiving reality. How to create a naturalistic gaming environment that opens a player’s mind to the transcendent elements within? In The Legend of Zelda, Miyamoto’s 1986 masterpiece, one moment you’re exploring a serene waterfall; the next, you’re summoning a powerful whirlwind with a shamanistic flute.

Koizumi invoked a recent example of primordial revelry from Splatoon 2, a squid-and-humanoid-based shooter game for the Switch, in which gun-wielding players spray opponents with blasts of colorful ink rather than bullets. “If you look on the screen, you’ll see all of these messy splatters,” he said. “This goes back to something basic and universal: kids making mud pies, that feeling of splashing mud and water around.” It’s a quintessential Nintendo riff on the perfunctory crutches of video game design, replacing the visceral spectacle of violence with the elemental joy of mud-shed.

The interplay of the particular and the universal also extends to Nintendo’s home city—you can find hints of Kyoto amid the designers’ flights of imagination. Fans have previously drawn the aesthetic connection between the abundant arches in Star Fox, for example, and the iconic vermilion torii gates at the Fushimi Inari Taisha Shrine. Last year, shortly after the debut of Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, players realized that the fantasy realm of Hyrule essentially maps to Kyoto. But, Takahashi said, “We’ve definitely always had the attitude that we can’t make products only for Japan.” Games created in Kyoto and voiced in Japanese must be translated and sold in countries around the world.

Over time, the company has built up localization teams in Europe and the U.S. that include scores of translators and Japanophiles. Their job is to scour the game scripts and rework anything potentially confusing. Few people who play Nintendo games are likely to notice their fingerprints, though there are pious aficionados who vigilantly assess their work, bridling at signs of impurity like Tolstoy devotees picking over a new translation of War and Peace.

Even when Nintendo’s fastidious development system gets everything right, successfully introducing and selling games into multiple cultures demands an additional, elaborate choreography. Before the Switch’s arrival, there were plenty of doubts about whether the traditional sales model would work, whether the company could get its consoles to market without exasperating users—and, above all, whether, in an age of endless digital distractions, Nintendo Mania was still contagious.

In the fall of 2012, the company was in one of its periodic slumps. It had just released the Wii U, the sequel to the phenomenally popular six-year-old Wii. The console featured HD graphics and a touchscreen controller, but from the start it felt off-kilter. The branding, for one thing. Wii U sounded so much like Wii, critics said, that it came across as a minor upgrade rather than an enthralling advance. Compelling games were slow to arrive, and sales were sluggish.

When things click for Nintendo, a new console triggers a slew of good fortune. The metronomic release of exclusive, tantalizing titles draws gamers to buy the console, which in turn increases sales. Then the console achieves critical mass among hardcore fans, and other companies scramble to adapt their most popular titles for Nintendo’s system. Third-party games from major and independent publishers attract new console buyers. Marketers seeking licenses—for apparel, cereal, children’s toothpaste—rush in, desperate to capitalize on the delirium. The resulting surge of revenue pumps up Nintendo’s profits and replenishes its R&D coffers to start the process anew.

Or not. With the Wii U, the cycle stalled immediately, and Nintendo sank into a multiyear slump. By the spring of 2014, it was posting its third consecutive year of losses, and people were comparing it to relics such as Sega, Nokia, and BlackBerry. Some suggested that Nintendo stop designing consoles altogether and focus instead on licensing its games for rival systems.

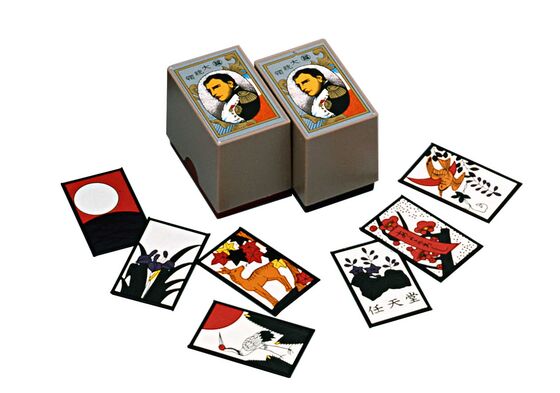

The notion of abandoning a core craft was anathema to Nintendo’s culture, though—the company was, after all, still selling packs of hanafuda, the flower-adorned playing cards that it set out with in 1889. The only place to play Nintendo games was on Nintendo devices. “If we think 20 years down the line, we may look back at the decision not to supply Nintendo games to smartphones and think that is the reason why the company is still here,” Satoru Iwata, then the company’s president, told the Wall Street Journal in 2013.

But investors’ faith continued to dim, and Nintendo shifted course. In the spring of 2015, it took a 10 percent stake in DeNA Co., a Japanese company that specialized in smartphone games and services. Several months later, it invested an undisclosed sum in Niantic Inc., a San Francisco-based app developer that had been spun off from Google. Nintendo was preparing to let Mario roam free.

Around that time, Iwata passed away from complications stemming from bile duct cancer, and Kimishima took over. Where Iwata was an accomplished game developer, Kimishima had spent more than two decades working for Sanwa Bank Ltd. He was known internally at Nintendo as a strong logistical planner and a generous mentor to younger executives.

The following year, Niantic released Pokémon Go, a mobile game that thrust Nintendo back into the news. In the 1990s, the company had paired Miyamoto with Pokémon’s creator, Satoshi Tajiri, to help him design the original Pokémon games. It now co-owns Pokémon Co., which handles licensing and marketing for the multiheaded entertainment hydra of TV shows, trading cards, comic books, and toys based on seemingly endless permutations of the fictional creatures.

Within hours of its arrival, Pokémon Go was a sensation. The game sent countless players wandering giddily around neighborhoods, shopping malls, and parks to capture Pokémon who’d been digitally embedded around the Earth, appearing on users’ screens when they drew near. Technically, Nintendo had played a peripheral role in the advent of Pokémon Go, but the phenomenon had some investors diagnosing early stage Nintendo Mania.

More symptoms emerged in November, when the company released the NES Classic Edition, a miniaturized, rebooted version of the Nintendo Entertainment System, the console that had made the company a household name in Europe and America in the ’80s. The updated version was carefully calibrated to rekindle the latent passion of lapsed fans, with 30 of the most popular NES games built in. (Unlike the original, there were no cartridges.) From the start, supplies were scarce. Stores were constantly sold out, so customers lined up for hours to await shipments of even a few units. But what seemed to some like a supply-chain disaster looked to others like a calculated strategy. At $59.99 per unit with no additional games, NES Classics were a low-margin item; much more important for the company was to whet the world’s appetite for Nintendo games in preparation for the Switch. To that end, Nintendo and DeNA also released Super Mario Run for iOS and Android, giving hundreds of millions of people an opportunity to help Mario scamper across their smartphones or tablets.

The strategy worked. By the time the Switch arrived in the spring of 2017, legions of people had been enticed to reconnect with their favorite childhood game characters on a proper Nintendo device. Over the next fiscal year, the Switch accounted for $6.8 billion of revenue. Nintendo’s existing handheld platform, the 3DS, kicked in an additional $1.7 billion, and sales of smartphone games rose 62 percent, generating $354.9 million.

Behind the white walls in Kyoto, Nintendo executives were already pondering how to stave off the next bust. At a news conference this April, Kimishima announced that he would step aside on June 28 and that Shuntaro Furukawa would succeed him. It was time, Kimishima said, for the next generation to take the lead. Furukawa, 46, had grown up in Tokyo playing Nintendo games; where Kimishima unwinds on the golf course, the new president plays Golf Story on the Switch. He joined the company in 1994, after completing a degree in political science, and spent 11 years at Nintendo of Europe before returning to Kyoto to take over corporate planning, working closely with Iwata and then Kimishima.

When it was Furukawa’s turn to speak, he noted that Nintendo makes “playthings, not necessities” and that if consumers stop finding its products compelling, the company could be swiftly forgotten. “It is a high-risk business,” he added. “So there will be times when business is good and times when business is bad. But I want to manage the company in a way that keeps us from shifting between joy and despair.”

Nintendo has a few plans in motion: a partnership with Cygames Inc., a Japanese developer specializing in mobile games, and the launch in September of an online subscription service for the Switch, which will allow gamers to compete against one another and play a slate of retro titles. The latter will help executives make the most difficult evolutionary step in the console life cycle: winning over the broader market of people who don’t typically play video games.

More radically to that end, in April, Nintendo began selling a toy line called Labo, which consists of cardboard assembly kits that gamers can use to transform the Switch’s detachable controllers into rudimentary motion-sensitive objects such as fishing rods or mini pianos. The contraptions can then be used to play accompanying games on the TV screen, by catching sharks with the rod, say.

The games’ code is somewhat customizable, so precocious kids can program new uses for each of the accessories. The concept feels like a cross between origami, Lego, and the block-assembling video game Minecraft. The goal in part is to win over parents who might otherwise balk at buying their kids a Switch—writing code being the most parentally acceptable form of screen time. “We want to create something that mothers and parents can have a sense of relief about their children playing,” Kimishima said.

In early June, Nintendo released a free online demo of the upcoming Mario Tennis Aces—a tournament game expected to be one of the first major attractions for its network service. Frustrated gamers complained on social media that connection issues were making the game unplayable, and Nintendo’s shares dipped 10 percent over a two-day stretch. “When we do a trial event ... we are learning about the technical infrastructure,” Nintendo of America President Reggie Fils-Aimé told Bloomberg Television at the time. “When we launch the game, it’s going to perform.” But the stock kept falling amid concerns about the Switch’s game lineup. By mid-June, it was at its lowest point in nine months.

If Nintendo, as a company, has long benefited from its artistic temperament, it suffers, too, from an artist’s restless insecurity. No matter how many times outsiders marvel at its work, its game designers must wake up each day, bike into the ivory cocoon of the R&D building, face the blank screen, and make something for the world. As it is for Mario, striving endlessly to reach Princess Peach, the prospect of fortune or failure is reborn each time a console powers up anew.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeremy Keehn at jkeehn3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.