The Chinese Powerhouse That Scares Banks—and Wants to Make Them Customers

Ant Financial dwarfs Goldman and Morgan Stanley in valuation but sees its future in catering to lenders.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Eric Jing, chief executive officer of Ant Financial, gathered his management team in between meetings at the Chinese financial conglomerate’s Hangzhou headquarters on June 6. The company had just closed a $14 billion funding round, one of the largest in history, and Jing was ready to celebrate.

Sort of. “Let’s raise our tea cups and have a simple toast,” he said, before quickly bringing an end to the festivities. “This will be the entirety of our celebration.” Jing, who took the helm of Jack Ma’s Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. spinoff in 2016, was telling his troops to be humble. But the episode also underscored the tough road ahead for Ant as it embarks on a major strategic shift.

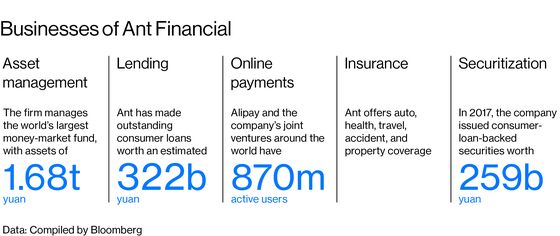

The company’s extraordinary rise over the past 15 years has come largely at the expense of traditional financial companies in China and, to a lesser extent, overseas. Ant’s wildly popular money-market funds have siphoned deposits from banks. Its online payment systems have disrupted card issuers. And its credit units have challenged lenders of all stripes.

But the company is increasingly turning the old model on its head. Instead of competing with banks and other financial firms, Ant sees its future in selling them computing power, risk-management systems, and other technology. Fees from such services may swell to 65 percent of revenue by 2021, from about 35 percent in 2017, according to a company presentation to investors seen by Bloomberg News. Some of Ant’s latest initiatives include upgrading Shanghai Pudong Development Bank Co.’s fraud-detection systems and a plan to provide technology to help at least four other banks extend loans to small businesses.

“We have been working with all the big banks, and we intend to even further deepen those collaborations,” says Jing, speaking with an international media outlet for the first time since closing Ant’s funding round. “We don’t want to be a big tree, we want to grow a forest with others.” BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest asset manager, has pursued a similar strategy with its Aladdin portfolio analytics software, and China’s Ping An Insurance Group Co. has said it wants to eventually get half its earnings from technology sales. Still, the scale and speed of Ant’s planned transition stands out.

The company has an extra incentive to move fast. Ant’s existing businesses—particularly its lending units and its 1.68 trillion yuan ($261 billion) Yu’E Bao money-market fund—are, like others in the industry, under pressure as Chinese President Xi Jinping tries to reduce financial risks in the world’s second-largest economy. Ant may soon face minimum capital requirements for the first time, say people familiar with the matter, as regulators step up supervision of companies that straddle multiple financial businesses. Ant says it has always worked closely with regulators.

Whether Ant can pull off the transformation is an open question. The company has to maintain a competitive edge in financial services while at the same time selling its tech to industry players. Other Chinese fintech giants, including Ping An and Tencent Holdings Ltd., are also hot on its heels. “Making more money from technology services might be a good story to tell for a better valuation,” says Julia Pan, a Shanghai-based analyst at UOB Kay Hian. “However, the growth from this sector might not be as fast.”

Jing says he enjoys the competition. He also has the backing of some of the world’s biggest investors. Participants in the company’s latest funding round included international heavyweights such as Temasek Holdings Pte., Singapore’s state-owned investment firm, and Warburg Pincus, a private equity firm that manages more than $44 billion. “Ant Financial’s tech capabilities and scale are hard to replicate,” says Ben Zhou, a managing director at Warburg Pincus.

Born out of an online payment system for Alibaba, the business has grown into a financial behemoth with few equals. Ant’s $150 billion valuation dwarfs those of Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley. The company’s Alipay and its global affiliates have 870 million users and handled as many as 256,000 transactions a second last year. The payment system—along with a competitor run by Tencent—has revolutionized the way people buy and sell things in China, prompting former Central Bank Governor Zhou Xiaochuan to predict in March that the country’s physical banknotes may one day cease to exist.

Ant, formally known as Zhejiang Ant Small & Micro Financial Services Group Co., has leveraged Alipay’s popularity to expand into everything from asset management to insurance, credit scoring, and lending. Its lending unit had originated an estimated 322 billion yuan of outstanding consumer loans as of the end of last year, according to a Goldman Sachs research report. Ant is also making a big overseas push, focusing on Southeast Asia, India, and other emerging markets after U.S. authorities blocked its bid to acquire MoneyGram International Inc. in January. The company will use most of the $10 billion raised from foreign investors in its latest financing round—widely seen as the precursor to an initial public offering—to build the overseas business. “This will expedite our global expansion,” says Jing, who joined Ant’s predecessor in 2009 after a two-year stint at Alibaba.

Some of China’s financial incumbents and their supporters have long pushed back against Ant’s rise. A commentator for one of China’s state-run television stations called it a “blood-sucking vampire” in 2014. But Jing expresses confidence about Ant’s ability to collaborate with other financial companies. While Ant didn’t disclose terms of its recent arrangements with banks, Jing explains the rationale for the cooperative approach this way: “My father told me if you close your hand when trying to hold on to something in your palm, the less you keep. If you open your hand, you will hold more.” —With assistance by Jun Luo

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Fenner at rfenner@bloomberg.net, Michael PattersonPat Regnier

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Editorial Board