A Meltdown Didn’t Kill Three Mile Island, But Shale Probably Will

A Meltdown Didn’t Kill Three Mile Island, But Shale Probably Will

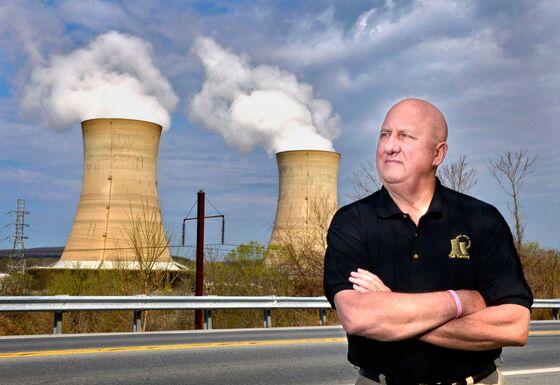

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In his four-decade career at Three Mile Island, Mark Willenbecher has watched the nuclear power plant overcome some towering odds. He was on the job on March 28, 1979, when one of its two reactors experienced the U.S.’s first and only nuclear meltdown. In the ensuing panic, his pregnant wife and young son had to flee their central Pennsylvania home. While citizens in Harrisburg, Pa., and other cities around the country held protests demanding Three Mile Island’s closure, Willenbecher suited up in radiation-protection gear and helped get the facility back online. Today, both of his sons are employed at the plant, where their father is training a new generation of nuclear reactor operators.

It’s not entirely uplifting work, either for Willenbecher or his students, who will wrap up their training next summer. That will be just a few months shy of Sept. 30, which is around when Exelon Corp. plans to take Three Mile Island offline—not because its technology is antiquated and unsafe, but because it’s no longer profitable. “They’re looking at us going, ‘Are we going to have a job?’ ” says Willenbecher, appearing pained in the living room of his split-level home a few miles from the plant, which he calls “a second home.”

For the cluster of small towns stretching along the Susquehanna River and south of Harrisburg, the closure of Three Mile Island will be a powerful blow. Last year alone, the plant sent $1.5 million in taxes and other payments to surrounding Londonderry Township, Dauphin County, and the local school district. And while the nuclear plant may not be the area’s biggest employer—that title goes to various entities with “Hershey” in their names, from a medical center to the amusement park just up the road—its 675 workers make good money. The average salary is $89,000, according to Exelon. That’s helped boost the median household income of Londonderry Township (population 5,242) to nearly $63,000, according to U.S. census data—higher than the statewide median of $55,000.

Through its 44-year existence, Three Mile Island has been a powerful draw for generations of highly skilled engineers, mechanics, and others who’ve often come up through the ranks of the U.S. Navy or top-flight universities. “These people go out to dinner, buy houses, go to Home Depot, go to Lowe’s,” says Steve Letavic, manager of Londonderry Township. “How do we replace that as a region? I don’t think you can.”

Across the U.S., more communities are grappling with such questions, as the owners of nuclear plants dating back to the 1960s and ’70s begin to put their facilities into premature retirement. That’s because the plants are having trouble staying competitive in an era of cheap natural gas, a product of the shale boom. Also, nuclear power’s attraction as a clean energy source has been eclipsed by no-emissions alternatives such as wind and solar power.

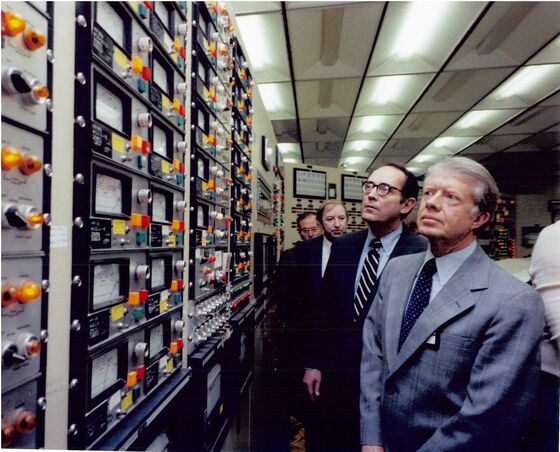

Three Mile Island began operating in 1974, a time of unbridled ambition for nuclear power. The Arab oil embargo had exposed America’s dangerous dependence on foreign energy, sparking a drive for independence. The enthusiasm for nuclear died on March 28, 1979, when equipment that pumped cooling water into Three Mile Island’s reactor No. 2 failed, triggering the meltdown. Sirens rang out across the region, residents fled en masse, and the national media poured in. Within days, President Jimmy Carter arrived, strapped on a radiation badge and protective boots, and toured the control room—a photo op designed to soothe a panicked nation. But the damage was done. Anti-nuclear activists went on the offensive: A march on Washington just weeks after the accident drew a crowd of 125,000, including the governor of California. More than 60 projects that were already under way got canceled, because of a combination of pushback from local communities and a regulatory crackdown.

Nuclear’s reversal of fortune is visible all over Three Mile Island. On the outside, four giant cooling towers climb into the Pennsylvania sky, but two of them haven’t emitted any steam since the accident. On the inside, some of the areas of the plant look like they’ve been frozen in time since the ’70s. Willenbecher is reminded of this whenever he introduces a young group of engineers to the control room, where red and green blinking lights, small computer screens, and large knobs and levers blanket the teal panels that cover the room from floor to ceiling. “They look at it like, ‘I think I saw this in the Apollo 13 movie,’ ” he says. “But it’s functional. It works well. And at the time, it was the top of the line.”

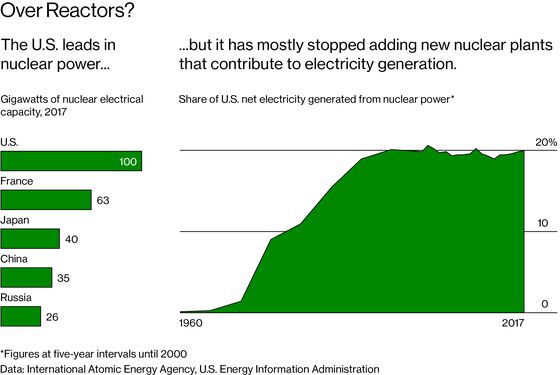

Like it or not, the U.S. remains the world’s nuclear energy leader, home to almost a quarter of the planet’s roughly 400 gigawatts of generating capacity, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency. That dominance, however, is looking increasingly shaky. While the U.S. fleet reached a peak of 112 nuclear reactors in 1990, only 99 are in operation today, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. And just one new plant has been licensed in three decades.

In France, nuclear power meets more than 70 percent of the country’s electricity needs, but in the U.S. that figure has hovered at about 20 percent for decades. Today, more than a quarter of U.S. nuclear power plants are failing to make enough money to cover their operating costs, raising the risk of more early retirements, according to a recent study by Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

Utility giants such as Exelon are looking to policymakers to help them keep aging plants up and running. At the federal level, the Trump administration has been trying for more than a year to figure out a way to bail out the country’s coal and nuclear fleets, saying their ability to generate power around the clock adds “resilience” to the national grid. Last week, Trump made his latest pitch, directing Energy Secretary Rick Perry “to prepare immediate steps” to halt the shutdown of such plants.

Even so, nuclear advocates have thus far had better success mobilizing resources at the state level. In Illinois, the state that leads the U.S. in nuclear power generation, lawmakers passed controversial legislation in 2016 to subsidize nuclear plants with so-called zero-emission credits. Exelon, which operates the largest nuclear fleet in the nation, owns the state’s six operational sites.

States including New York and New Jersey have enacted similar policies. Pennsylvania has been a tougher sell. A nuclear energy caucus in the state legislature has failed to pass anything helpful yet. Its efforts have been stymied, in part, by forces supporting the state’s booming natural gas industry.

Exelon, which spent $4.5 million in federal lobbying last year, isn’t ready to call it quits. The company is seeking policy changes at the state, regional, and national level “that properly values nuclear energy for the value it provides from an environmental standpoint, from a resilience and reliability standpoint, from a fuel diversity standpoint, and as an economic engine for the communities in and around the plants,” David Fein, Exelon’s vice president for state government affairs, said in an interview.

Part of the problem is that, after decades of stagnation in the nuclear energy sector, Americans simply aren’t engaged in the subject—whether for the technology or against it. “People on both sides of the nuclear debate are graying,” says Eric Epstein, the longtime chair of the watchdog outfit Three Mile Island Alert. “If you attend a nuclear meeting, it reminds you of being at an AARP social function.”

While the name Three Mile Island may no longer resonate with young Americans, surrounding communities won’t soon forget its presence. When the plant finally closes, crews will remove the spent nuclear fuel from its reactors and store it in long-term storage containers on-site. Then they’ll dismantle and cart off buildings and other infrastructure, some of which is radioactive. The U.S. currently has no final resting place for spent nuclear fuel, with debate and lawsuits continuing to swirl around one possible site, Yucca Mountain in Nevada. As a result, no retired U.S. nuclear power site has ever reached the point where it doesn’t need to be guarded.

“You worry, what will happen if it shuts down?” says Pat Devlin, an otherwise laid-back 36-year-old who works just a few miles north of the island, in Middletown, Pa. A Navy veteran, Devlin and a couple of friends opened Tattered Flag Brewery & Still Works in 2016 on a stretch of downtown Middletown that could use more revitalization. The locale has been a hit with Three Mile Island employees, in part thanks to a smooth-tasting, double India pale ale that Devlin and his partners christened “TMIPA” in honor of their history-making neighbor. “You’re talking about people with some financial freedom that can come to a craft beer bar,” Devlin says, looking regretful. “We’ll obviously see that go along with a couple of other local businesses, which is a shame.”

Around the corner, Barbara Scull is wondering what the closure will mean for Middletown Public Library. A few years back, the power plant donated a cluster of eight desktop computers as part of its annual gift of technology to the library. On a quiet morning, she walks past them as a couple of senior citizens tap at keyboards and stare into the screens. A sign hanging above their heads reads: “Three Mile Island. Clean. Safe. Reliable.”

Scull points to a shelf of books that explore the complexity of those claims. Reaching past titles such as Three Mile Island: Thirty Minutes to Meltdown and The Nuclear Survival Handbook, she grabs the more academic-sounding Atomic Accidents: A History of Nuclear Meltdowns and Disasters. Scull recalls she would often steer local students who were working on projects about nuclear’s place in America’s energy mix to this corner of the library. “I haven’t had to assist anyone recently,” she says with a sigh. “Even this is drying up.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.