This Financier Became a Fed Power Player—From the Inside and Outside

This Financier Became a Fed Power Player—From the Inside and Outside

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- John Williams has fans at the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, part of the Brookings Institution think tank in Washington. When news leaked in March that he was the front-runner to lead the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the group’s director, David Wessel, immediately lauded the potential move in an emailed reply to a reporter. When the formal announcement was made a week later, former Fed Chair Janet Yellen, an affiliate of the center, issued a glowing press release. Brookings posted an article detailing his contributions to the think tank.

Williams’s promotion from San Francisco district president was important for the Fed, because the New York chief is among the most powerful central bankers in the world. It was a big moment for the Hutchins Center, because Williams is Yellen’s protege and was a Fed colleague of another affiliate, former Chair Ben Bernanke. And it was consequential for Glenn Hutchins, the private-equity financier who launched the center with a $10 million donation five years ago. He co-led the New York Fed search committee that chose Williams.

In backing a haven for top Fed expats and guiding a personnel move that will shape monetary policy for years, Hutchins has exerted remarkable outside influence at the central bank—arguably more than any living financier. As the debate heats up over the Fed’s role in the economy, the center that bears his name is emerging as a thought leader in the field. It’s also sometimes criticized for hewing closely to central bank orthodoxy. Brookings is providing “Fed analysis of the Fed,” says Mickey Levy, a member of the watchdog Shadow Open Market Committee and chief economist at Berenberg Capital Markets in New York. “Most of their analysis, which is good quality, is based on the assumption that what the Fed has done is just about right.”

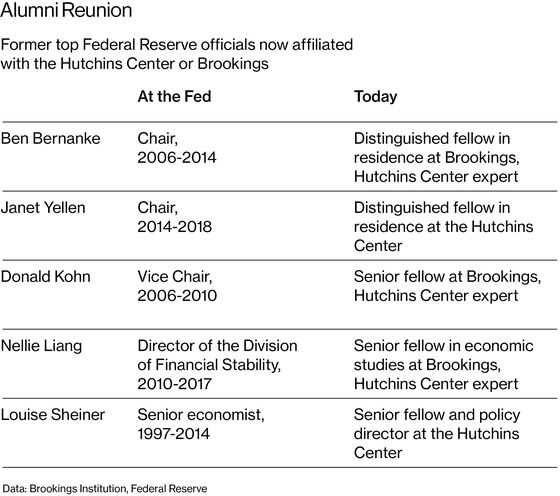

Bernanke and Yellen now share a hallway with former Fed Board Vice Chairman Donald Kohn. It’s a running joke at Brookings that their corridor is the “FOMC-Former Open Market Committee,” a play on the name of the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee. Nellie Liang, the former director of the Fed Board’s financial stability division, is listed as a Hutchins Center expert. Louise Sheiner, a longtime Fed Board economist, is the center’s policy director.

Hutchins doesn’t see the center as a Fed booster. He views it as a forum for robust discussion and, in a conversation in his office in New York, he says his influence at both the Brookings center and the regional Fed is limited: A committee picked Williams—he just led it; he had the idea for the Hutchins Center and bankrolls it, but he doesn’t make hiring decisions or set research agendas. “If it’s been influential, it’s because it’s filled a gap that was needed,” says Hutchins.

Titans of business and finance often seek higher validation. For some, that means a run for the White House or another high office. Others crave the splashy spotlight of yachts and parties. But there’s a breed that aims to influence public policy, to leave a mark on something bigger than a balance sheet. Hutchins, 62, falls squarely in that camp. Philanthropy and personal interest, not profit motives, drive his engagements with the Fed, according to interviews with seven of his Wall Street contemporaries and economists who know him. They spoke on condition of anonymity so they could be candid. Skeptics say he thinks he’s always right and wants his voice heard; friends say he wants to put his insights to good use.

Robert Wolf, founder of 32 Advisors LLC in New York and former chairman of UBS Americas, falls into the latter camp. “Glenn likes to talk economics, and he likes to talk policy,” he says. Hutchins himself said in 2014 that he’d “taken a real strong policy interest in economic policies that relate to business success,” speaking at a Fortune magazine event. “Some small number of us need to be able to be deeply engaged in the process in order to guide the policy-making process in the way that’s likely to generate the most economic growth and create the least amount of friction in the system.”

The venture capitalist isn’t new to philanthropy. Hutchins spent much of his recent career at tech investor Silver Lake Partners and is a co-founder of North Island, which focuses on financial services technology. He’s held public roles as well. He’s served as vice chairman of the Brookings board since 2005. He was an adviser in Bill Clinton’s administration, donates to Democrats, golfs with former President Barack Obama, and endows the Hutchins Center for African and African-American Research at Harvard University.

When it comes to economic policy, his donation struck a rich vein. Beyond the fact that the center is home to two of the four living former Fed chairs, current chairman Jerome Powell spoke at one of its events before getting the job. Williams headlined an event there shortly before his promotion. For a new organization, the Hutchins Center has serious cachet.

The center provides a needed outlet, in Hutchins’ view. After joining the New York Fed board in 2011, he realized that there weren’t many open forums at which central bank outsiders could learn about monetary policy up close. So when he decided to make a big donation to Brookings as part of a giving campaign, he earmarked it for an economic policy center.

He bumped into David Wessel in the lobby of the St. Regis Washington hotel in early 2013 and told him about the idea. The longtime Wall Street Journal economics editor and author of the book In Fed We Trust pitched himself to Brookings leaders as a candidate to lead the initiative. Wessel landed the job as Hutchins Center director and made short order of helping to recruit Bernanke, who was stepping down from his role as Fed chairman in 2014.

Founding the center allowed Hutchins to put some small mark on Fed thinking. The past year turned it into a tattoo. In 2017 and early 2018, Hutchins helped co-chair the search for the New York branch’s new president. That gave him a chance to prioritize certain qualities and help vet candidates through the interview process, though finalists were settled on with input from the rest of the board and Fed chief Powell. He also had a vote on the final decision.

In Williams, the committee chose a longtime Fed economist who’s been president at San Francisco for the past seven years. Fed insiders and many economists cheered, while criticism poured down from Democrats and some advocacy groups, which had called for a woman or minority appointment and fresh blood.

As Hutchins worked toward that controversial decision, the center at Brookings was raising its profile on key issues facing the Fed, hosting a much-talked-about conference on the future of inflation-targeting by the central bank in January 2018. The topic—one that Williams had been pushing the Fed to think about—was debated by a group of economics luminaries. Two active policymakers spoke on panels, as did Bernanke and former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers.

Such forums can provide valuable opportunities for debate. They can also echo, even reinforce, standard Fed thinking, critics say. “Brookings has turned itself into a holding pen for former Fed officials,” says Karl Smith, a senior fellow at the Niskanen Center, another think tank in Washington. “They are at the center of the status quo” thinking on monetary policy, he says. The libertarian Cato Institute or the Peterson Institute for International Economics also focus on monetary policy and have influential voices, but they lack such tight connections inside the Fed.

Wessel, who spent three decades working for the Journal and remains a contributing correspondent, says it’s unfair to accuse Brookings of encouraging groupthink. Frequent Fed critics—from Stanford University’s John Taylor to Potomac River Capital’s Mark Spindel—have spoken at the Center’s events, he points out. “We provide a venue for a conversation about the stuff that the Fed can’t or won’t talk about,” he says.

Hutchins says he hopes the events have helped to move Fed debate into the light of day. Brookings events are web-streamed, open to the public, and often include question-and-answer sessions in which online viewers can submit queries. They are also occasionally followed by luncheons that aren't broadcast to the public, whose guest lists can include conference participants, Brookings donors, and journalists.

The Hutchins Center’s funding is up for renewal this year, and the benefactor says he thinks he’ll probably reinvest, though those discussions have yet to happen. Asked where he sees it headed, Hutchins notes that he’s hoping for a little more focus on fiscal policy—that is, the taxes and budgets controlled by Congress—but that he won’t intervene. “You can’t tell them what to do, it’s their thing,” he says. “I’m the donor, and that’s about it.”

--With assistance from Max Abelson.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Pat Regnier

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.