Shocking the Spine Offers an Alternative to Opioids

Shocking the Spine Offers an Alternative to Opioids

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Like millions of people caught up in America’s opioid crisis, Rick Surkin used to take a pill just to get out of bed in the morning. Until last year, the former firefighter relied on thrice-daily doses of the powerful painkiller OxyContin to numb the agony from a ruptured disc in his back. “You can take enough pills to mask the pain, but they take over your life,” he says. He’s been able to get back on his surfboard, and into the California surf shop he manages, because a medical implant sends 10,000 pulses of low-voltage electricity through his spine per second.

The series of tiny shocks, known as neuromodulation, has kept Surkin comfortable enough to ditch Oxy. “There is a lot more time I’m pain-free now,” he says. That allowed the 64-year-old to resume his outdoorsy lifestyle, but the benefits are more than just physical: His relief has also afforded him more energy and better moods, helping to revive his relationship with his wife. “I’m back to the person she married,” he says.

After half a century on the fringes of medical science, neuromodulation is becoming a mainstream alternative to painkillers for those who can afford it. Sales of spinal stimulators, used mainly to soothe hurting legs and backs, rose 20 percent to $1.8 billion in the U.S. last year. These pricey devices wouldn’t be mistaken for Iron Man’s one-of-a-kind glowing chest implant—don’t expect repulsor rays or flight—but doctors see potential for similar therapies to treat migraines, neck pain, and other ailments that afflict millions. “Particularly as opioids are being limited, you want physicians to have an option that gives this sort of an impact,” says Rami Elghandour, chief executive officer of Nevro Corp., the maker of Surkin’s implant. His company is running two dozen studies on how electricity can help ease pain.

The idea dates to Roman times, when people applied controlled shocks from electric fish such as the black torpedo to treat everything from migraines to gout. The first modern spinal implants arrived in 1967, the technology modified from that of the pacemaker. Those early devices were touchy: An errant shrug could deliver an unexpectedly large shock, rendering everyday tasks such as driving off-limits.

While training with other firefighters in his hometown of Huntington Beach, Calif., Surkin grabbed a 35-foot extension ladder the wrong way and ruptured a disc. His distress persisted through four major surgeries and seven procedures over 15 years, keeping him away from such outdoor passions as golfing, waterskiing, and driving off-road vehicles. “I went from being 100 percent to being down on my knees,” he says. “I suffered from chronic pain from that point on. It never went away.”

As physical therapy failed and his prescriptions got stronger, Surkin turned to more innovative options. His first attempt at upgrading his operating system, a spinal cord stimulator implanted in 2010, turned out to be a bust. The first-generation device caused paresthesia, a tingling similar to what one feels after hitting a funny bone, and pulsing vibrations. He found those sensations as annoying as the chronic pain and turned it off. In 2016 he heard about the Nevro HF10 from his doctor and waited eagerly for more than six months for insurance approval. “When you live in chronic pain, you get desperate for relief,” he says. “Anything that could improve my life, I was willing to try.”

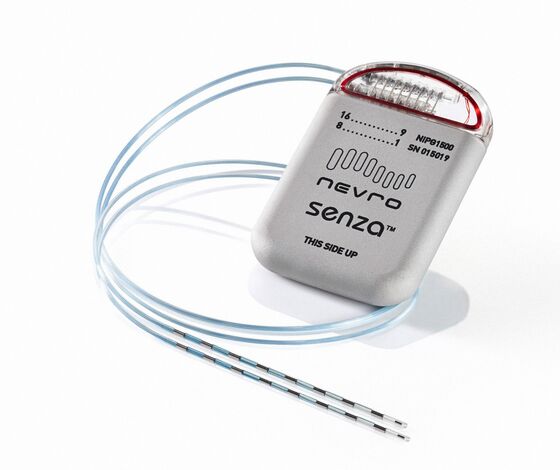

The $30,000 implant sends waves of electricity through the spinal cord to dampen errant signals from damaged nerves. A thin wire called a lead, with an array of electrodes attached, is threaded along the spine. That’s connected to a device that includes a battery and a neurostimulator, typically implanted in the lower back. The device uses high-frequency pulses, unlike the slow, steady waves of older models.

At that price, about 60,000 people a year are getting spinal cord stimulators. But 820,000 a year are candidates for the implants, creating a $20 billion market opportunity, estimates Jason Mills, a medical technology analyst at investment bank Canaccord Genuity. “Everyone is looking at spinal cord stimulation for other areas,” Mills says. “That could further expand the opportunity.”

Even widespread adoption of the devices wouldn’t do away with the need for opioids. A patient seeking temporary relief after surgery, for example, would still look to a pill instead of an implant. And many of the most at-risk patients likely won’t be able to afford the tens of thousands of dollars for surgery and upkeep, says Molly Rossignol, an addiction medicine specialist. “I worry about the number of people who are going to be able to access it based on what insurance they have,” she says. Still, she notes, going straight to neuromodulation could help save the right chronic-pain patients from spending years on drugs.

Device maker Abbott Laboratories is among the biggest companies exploring the technology’s potential. Its implant stimulates a spot in the spine known as the dorsal root ganglion (DRG). There, a clump of sensory nerves coalesce and, when damaged, can form an unrelenting pain conduit to the brain. Allen Burton, Abbott’s medical director of neuromodulation, compares it to a fuse box with a short circuit, triggering signals that cause pain far away. “This is a critical piece of neuroscience, having the signals understood in great detail,” he says. “For the first time, we are learning to adapt to the language of the nervous system.”

Chef Tony Lawless uses Abbott’s DRG device to help treat his chronic pain, caused by years of rheumatoid arthritis that eventually led him to have his left foot amputated. During that time, he took anything he could to function, at one point relying on a dozen Vicodin pills a day, plus alcohol. When that didn’t work, his doctors transitioned him to morphine. A New Englander with a fondness for skiing, he took to using a bucket—essentially a chair and a footrest perched atop a single ski—because he couldn’t bear standing on his prosthesis for the few minutes it took to get down a run.

Lawless obsessively searched for ways to treat his pain, and if one thing didn’t work, he moved on to the next. He learned about an expert doing cutting-edge work on the femoral nerve, and although he wasn’t healthy enough to join that trial, his doctor suggested the DRG stimulator instead. He did a test run with a temporary implant, a feature of many of the newer devices, and took a five-mile hike around Central Park in New York. He hadn’t walked that far in a decade.

“This was like a miracle for me,” says Lawless, 58. “The next day, both my legs hurt, but it was muscle pain. I felt so free.” The following winter, he was back on his conventional skis. While the pain isn’t gone completely, the DRG implant allowed him to massively reduce his self-medicating. Now a single prescription of Norco, a combination of the narcotic hydrocodone and acetaminophen, can last months depending on how hard he pushes himself on the slopes.

Until now, that degree of freedom hasn’t really been available to other sufferers of chronic pain. Many aren’t even aware of the treatment options. With opioid prescriptions falling (the legitimate ones, at least), it’s critical to have something that offers relief, says Alexander Taghva, a surgeon who specializes in neuromodulation.

And there’s a growing pile of data suggesting that spinal cord stimulators ought to be high on the list. Nevro said in its 2016 clinical trial that after two years about three-quarters of patients using the HF10 reported a 50 percent reduction in pain. Surkin’s results resembled those of Nevro’s best cases: He has no tingling or awareness of the device at all. He’s among the 40 percent of patients using the device who’ve been able to stop taking opioids entirely. The former firefighter says surfing is his drug now. “I’m back to what I used to be able to do,” he says.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Julie Alnwick at jalnwick@bloomberg.net, Jeff Muskus

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.