Wall Street Needs a New Tom Wolfe: John Micklethwait

Wall Street Needs a New Tom Wolfe: John Micklethwait

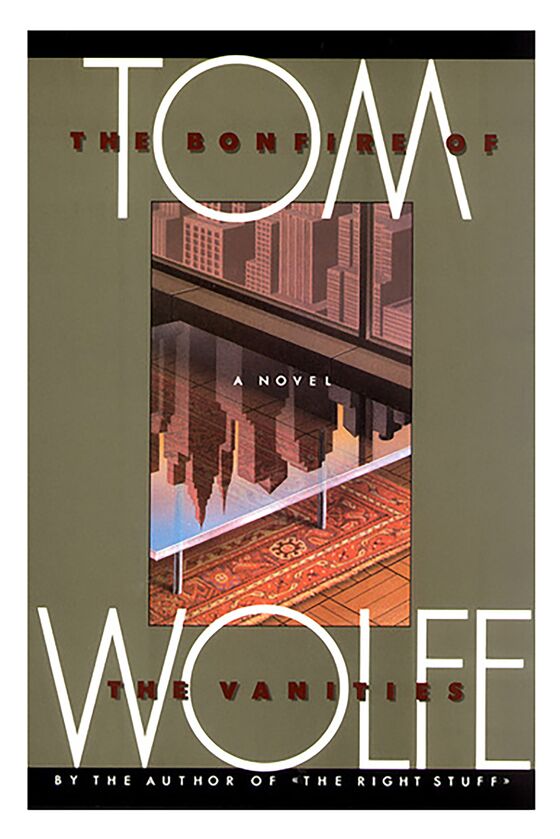

(Bloomberg) -- There are many reasons to praise Tom Wolfe, both as a novelist and as a journalist. If Charles Dickens defined Victorian London, then the capital of the world, Wolfe, who died on May 14 at 88, held up a similar mirror to modern America—and New York in particular. One of Wolfe’s less celebrated achievements was that he was a great novelist of finance—the only one that this frenzied era of moneymaking has produced.

The Bonfire of the Vanities was arguably the first great financial novel since Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now. Many eminent American writers have looked at the victims of Wall Street and broader capitalism, including Sinclair Lewis and John Steinbeck. But Wolfe was the first American one to look at the victors—the “Masters of the Universe”—like Sherman McCoy, who sold bonds for a living. Bonfire drills into their lives, their hangups and petty ambitions, enumerating their virtues and vices often literally (saying how much their clothes, apartments, and lunches cost).

Looking back, especially through the harsh lens of the 2008 financial crisis, it’s strange how sympathetic Wolfe was to Sherman McCoy. This is a relative judgment: We first meet Sherman kneeling on the floor pathetically trying to put a leash on a dachshund, and Wolfe skewers the bond trader’s insecurities about “going broke on $1 million a year”—just as he savages the “social X-rays” and freeloading English journalists. But as that implies, it’s equal-opportunity skewering. McCoy is a much more nuanced character than, say, Augustus Melmotte, the villainous French antihero of The Way We Live Now (which Trollope partly based on the Crédit Mobilier scandal), let alone the cartoonish Gordon Gekko in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street.

Wolfe spent time on trading floors, tried to explain the excitement of the deal—and the all-American sorts who greedily and weakly end up being swept away by it. He gave Charlie Croker, the Atlanta real estate developer in A Man in Full, a similarly rounded treatment.

In some ways the remarkable thing is not that Wolfe wrote about finance in this fashion but that so few people have followed him. Out of all the amazing things that have happened to America in the past half-century, the rise of Wall Street—and the creation of wealth through what Trollope called “the manufacturing of shares”—is one of the most incredible. And yet what great fiction is there to catalog this era?

Some would point to the TV show Billions, which looks at hedge funds. And some would say that John Lanchester’s Capital was a British Bonfire. Modern American writers from Bret Easton Ellis to Jonathan Franzen have looked at the consequences of this new Gilded Age—in the same way that F. Scott Fitzgerald captured the vanities of the previous epoch. But American fiction has not followed Wolfe onto the trading floor, not dived into the mechanics of money and its effect on society, the way Dickens and Victor Hugo did in a different age.

The best books about modern finance have been nonfiction—like Michael Lewis’s Liar’s Poker and The Big Short. All our lives have been shaped by finance and economics, and yet hardly anyone has found a way to use fiction as a vehicle to explore these things. Whatever you think, Wolfe leaves a big space behind him.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.