Amazon Has a Rare Chance to Get More Diverse Fast

Amazon Has a Rare Chance to Get More Diverse Fast

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- By the end of the year, Amazon.com Inc. will announce the location of its second headquarters. It’s hard to overstate the local impact of 50,000 new jobs, and Amazon knows it: It’s staging a months-long reality show of a selection process to see which city can offer the best package of financial incentives, real estate, and livability, alongside other requirements.

The search for a second home gives Amazon something else: an unprecedented opportunity to deal with a problem besetting all of big tech—a stunning lack of diversity. And Amazon is one of the bigger sinners. Men make up 73 percent of its professional employees and 78 percent of senior executives and managers, according to data the company reports to the government. Of the 10 people who report directly to Chief Executive Officer Jeff Bezos, all are white, and only one—Beth Galetti, the head of human resources—is a woman. The board of directors is also resisting shareholder pressure to improve gender balance.

Amazon doesn’t make public the gender breakdown of workers in technical roles, but anecdotal evidence suggests they skew just as male as the leadership. At weekly Amazon Web Services meetings, where some 200 employees come ready to present their most recent results, it’s rare to have more than five women in the room. Over the years, workers at Seattle headquarters have complained to the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries that there aren’t enough men’s bathrooms.

Restroom lines aside, the imbalance isn’t good for any company. The business case for diversity has been made ad nauseam, and most companies—Amazon included—at least pay lip service to the idea that diversity helps the bottom line. But even the most dedicated companies say that changing workforce demographics will take years, maybe decades.

Amazon, however, can radically change the makeup of its workforce in a much shorter time. As it prepares to hire thousands of new employees, the company could pledge to ensure that half of the workers at HQ2 are women, and that people of color are represented in line with the local population. Amazon has proven it can dramatically reshape whole, seemingly disconnected industries. Surely it could hire more women.

“There’s no reason not to. The talent is there, technically and nontechnically,” says Kristi Coulter, who left the company in February after 12 years in various roles. The trick is convincing Bezos it matters. “If he cared, he’d have a team of advisers that looked more like our customer base. If he cared, he would be doing something really ballsy and bold that you and I would never dream up in a million years.”

Academic literature has for years documented diversity’s business benefits. Companies with diverse leadership teams post better sales and financial returns. They’re likelier to win new markets, introduce products, and innovate. The effects are particularly strong when internal diversity includes people who represent a company’s customers.

The most popular explanation is diversity in itself improves management. The idea is that men and women, or people of different races, see the world in different ways, and diversity of perspective leads to less groupthink and better decision-making. Maybe Amazon should think of it in another way. What if those companies have achieved better results because their hiring process is better? And what if, by stripping out a bias that favors white men, they’re truly able to identify the candidates’ talent, skill, and acumen?

It wouldn’t be the first time that what we thought we knew about talent turned out to be false. For a century, baseball scouts identified prospective major leaguers through careful, personal observation—a process that turned out to be full of misconceptions and bias. When Billy Beane of Moneyball fame found a more reliable way to evaluate players, he turned a small-market team into one of the best in baseball. He also fundamentally changed the sport’s market for talent.

In the world of classical music, the proportion of women in professional orchestras jumped to 25 percent from 5 percent in the 1970s and 1980s, but only after most orchestras instituted a “gender blind” audition process that shielded musicians from the jury with a screen. “The best thing that companies can do is to throw out their intuition that they know whom to hire and what to look for,” says Catherine Tinsley, the Raffini Family Professor of Management at Georgetown University. “If you see gender differences in placement, then you should first be asking if there is something about the context or the environment that is positioning men and women differently.”

The suggestion that Amazon has a talent problem may sound ridiculous. It’s one of the world’s most valuable companies and, according to Glassdoor, some 2.5 million people researched employment at Amazon in the most recent month, making it one of the site’s most intriguing employers. (Only 1.7 million looked for information about working at Google.) By most metrics, Amazon ain’t broke, so there’s no reason to fix it.

At the same time, it’s hard to imagine what might have been—or still could be—if the decision-makers at Amazon included more women and people of color. It’s a company defined by its boundless ambition. If diversity in the workforce creates a more powerful, interesting, and innovative Amazon—well, good luck to the rest of us.

Amazon is sensitive to this. In the pageantry of choosing a city for HQ2, it has been looking at gender and racial diversity in the workforce, according to people close to the process. Its executives have also met with local public school officials to gauge interest in possible partnerships in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. They’re thinking about who’s in their hiring pipeline, now and in the future.

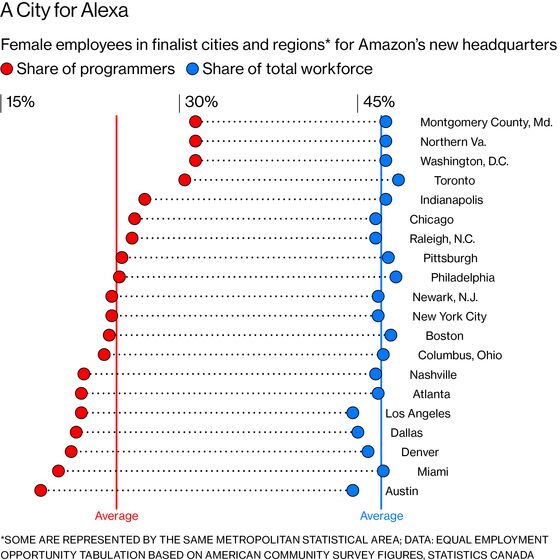

If that’s the case, Amazon should build HQ2 in Chicago. Or Toronto, or Washington, D.C. We looked at the demographics of the workforce, and among the 20 metro areas on the company’s short list, these are the only ones that are above average on three relevant measures of diversity: percentage of people of color in the workforce, female-to-male ratio among programmers, and overall female participation in the workforce. (For those trying to handicap, Toronto, being outside the U.S., would be widely considered an anti-Trump choice; Washington would put Bezos near the Capitol and the newspaper he owns; Chicago lacks the political overtones of the other two.)

Whatever city it chooses, Amazon could consider making changes to its hiring process that would level the playing field. It could set goals for diversity across the company and make its progress public. Smaller tech companies have shown they can beat the averages when they try. Slack Technologies Inc., a workplace collaboration company, made hiring women and people of color an explicit priority three years ago. Today women make up almost half of its managers and one-third of its technical employees.

Or Amazon could end its employee referral bonus, a practice that, like alumni preference in college admissions, tends to undermine diversity. Or it could tweak the bonus criteria, rewarding employees who successfully bring people of color and women into the workforce.

As of now, a high-ranking executive says, most of Amazon’s hiring managers are left alone to meet recruitment goals, which often leaves them leaning heavily on their personal networks and internal candidates—neither of which lends itself to increased diversity. “There’s no incentive or alignment with any sort of diversity initiative,” says the executive, who asked to remain anonymous. “Whatever you can do to get butts in seats, that’s almost certainly what you’re going to do without regard to any bigger mission.”

Amazon could add more support for recruiting and better train recruiters to focus on broader candidate pools, the executive suggests, or allot additional head count to managers who successfully add people of color and women to their teams.

And about that candidate pool: Amazon’s job applicants do skew male, more so than rivals Google and Facebook Inc. Although the company may be the most-searched on Glassdoor, twice as many men as women are looking for openings there. (The site doesn’t track race.) That’s not surprising—male STEM graduates outnumber women 3 to 1—but Amazon makes it worse by loading up its job ads with words that research suggests appeal to men.

We asked Textio Inc., a company that helps businesses develop gender-neutral job postings, to analyze Amazon employment ads. Amazon’s are much more likely than other tech companies’ to use aggro words and phrases such as “wickedly” or “maniacal.” According to Textio, the data revealed that about 30 percent of Amazon’s posted job descriptions skew male in their language, whereas only 1 percent skew female, an imbalance that doesn’t plague most of its tech industry peers.

There’s no single, simple fix for a hiring process that, like in the rest of tech, has favored white males for decades. If it were only about having less gendered job ads, well, Facebook and Google are doing that, Textio says, and their workforces aren’t significantly more diverse than Amazon’s.

Still, if any company can figure this out, surely it’s Amazon. There’s at least as much value in hiring women and people of color as there is in moonshots like reinventing grocery stores, delivering packages by drone, perfecting the smart speaker, and tackling the broken health-care system.

Recruiting is only the first step. Amazon’s hiring process, from the language in its job ads to an internal process that prizes efficiency above all else, reflects its broader organizational culture. More than any of the big tech companies, it’s known to be a relentlessly demanding work environment. Bezos likes to brag that employees work “long, smart, and hard.” Data is king. Emotions are unprofessional.

“It’s not for everyone,” says Muge Erdirik Dogan, director of Amazon Flex, the company’s last-mile delivery service. “It’s an ownership culture and you need to come to work every day and treat whatever business you’re working on as if it was your own business… it’s an amazing place, it’s not an easy place.” In 2015, a New York Times story revealed how bruising Amazon’s culture could be to women (and many men). Amazon disputes that portrait. But shortly after, it implemented a long-planned change to its parental leave policy. It now offers 20 weeks of paid leave for birth mothers and six weeks for all new parents regardless of gender. It encourages employees to use the time. It also created what it calls a “leave-share” program, which helps employees transfer paid time off to partners who work elsewhere but might not get leave through their own employers.

Plenty of tech companies offer paid leave, many of them more generous than Amazon. But it’s the first to create a leave program for partners who work elsewhere, a policy that in a small way illustrates Coulter’s broader point: When Amazon wants to solve a problem, it can. HQ2 offers a chance it shouldn’t pass up.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.