Elliott Broidy and the GOP’s Bad Hacking Karma

Elliott Broidy and the GOP’s Bad Hacking Karma

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Los Angeles attorney Robin Rosenzweig got an email on Dec. 27 that appeared to be a Gmail security alert, she offered her password as requested. But instead of sending it to Google, she handed it to a group of hackers. Their target wasn’t Rosenzweig, but her husband, Elliott Broidy, a top Republican donor, defense contractor, and friend of President Donald Trump. Rosenzweig’s mistake made it easy. With her password, the hackers accessed her Google Docs account, where she kept a list of more passwords, including one associated with a corporate account from her husband’s money-management firm, Broidy Capital Management.

If that sounds familiar, it’s because John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager, fell for a similar ruse during the 2016 presidential race, resulting in a devastating, weeks-long leak of private emails that arguably helped put Trump in the White House. But it’s not just the fake Google security alert that is making Republicans feel as if they’re suffering a bout of hacking karma. Whoever took Broidy’s emails has doled out curated selections to media outlets, including the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and Bloomberg News.

The leaks, from a group called LA Confidential, have led since March to a succession of embarrassing stories on Broidy’s attempts to trade his proximity to the president for his benefit and that of wealthy clients in Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates, and elsewhere. (Broidy also admitted paying $1.6 million to a former Playboy Playmate who had an affair with him and became pregnant, a deal negotiated by Trump attorney Michael Cohen.) American national security officials concluded that in 2016 the Democrats were hacked by Russian intelligence operatives trying to tip the scales of the U.S. election. Broidy believes he was targeted for political motives as well—in his case, by UAE rival Qatar. He claims Qatar was retaliating against him because he has spoken out about what he sees as that country’s support for terrorism and its friendliness with Iran. If Qatar were behind the hack, it would be the latest example of a foreign power trying to influence domestic American politics by exposing the secrets of the political elite.

Broidy allowed Bloomberg to talk with security experts as part of an effort to focus more attention on the hack (and less, presumably, on the leaks). In March, he filed a lawsuit in California accusing Qatar of orchestrating the attack. The experts confirmed that the hackers probably got away with tens of thousands of emails and other documents, a cache they could continue to dribble out for months. “It is a horrible experience to have business and personal information stolen and disseminated,” Broidy told Bloomberg in an email. “This attack on our privacy has taken a great emotional toll on me, my family, and my employees.”

A spokesman for the Qatari embassy in Washington said Broidy’s lawsuit was “without merit or fact.”

In trying to change the subject, Broidy faces many of the same problems Clinton’s team did. Reporters, political operatives, and members of Congress tend to see politics as a game in which all’s fair. The media has treated the emails as the foundation of a series of dispatches about how Washington works in the Trump era, eclipsing questions about how the documents were made public.

And then there’s the karma. Republicans, if they talked about hackers at all in 2016, emphasized that it’s difficult to tell who’s behind an attack and that it was really the Democrats’ fault for being so lax when it came to cybersecurity. The Democrats didn’t make it that hard for the Russians, but they were masters compared with Broidy and his team. Rosenzweig, like Podesta, could have avoided the mess if she had taken five minutes and switched on Google’s easy-to-use, two-factor authentication tool, which supplements an account password with a six-digit code sent to a user’s phone.

The hackers got access to emails from Broidy and five of his employees because they all used the same password, his security team confirmed. That password was different from the corporate password used by Broidy’s wife that hackers took from her Google Docs account. Investigators are still looking at how the hackers obtained that master password, according to a person familiar with the probe. The company’s defenses were so weak that the intruders didn’t even need to deploy specialized hacking software, which might have helped investigators identify the group behind the breach. They just signed in as Broidy or one of his employees and started reading. “If there had been two-factor authentication in place, many of these attacks would not have been possible,” says Sam Rubin, vice president of Crypsis Group, a security advisory firm, who was asked by Broidy’s lawyer to speak on his behalf. “Securing the human, as they say, is always going to be the weakest link.”

Long an influential figure in California political circles, Broidy, 60, spent years working his way back from the stigma of pleading guilty in 2009 to paying almost $1 million in gifts to officials close to the comptroller overseeing the New York State pension fund in exchange for allowing his private equity firm to manage $250 million in public funds. He raised money for several Republican candidates in 2016, including senators Ted Cruz of Texas and Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, before settling on Trump. He quickly gained the appreciation of Trump insiders by connecting the candidate to his network of wealthy Jewish donors, who wanted to shape the inexperienced candidate’s approach to Israel. Last year, Broidy and his wife gave at least $500,000 to GOP candidates and committees, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

That performance helped solidify a close relationship with Trump, and the leaked emails provide an intimate portrait of how Broidy worked to profit from it. According to a three-page summary of a meeting in the Oval Office last October, Broidy touted the creation of a counterterrorism task force consisting of 5,000 Muslim soldiers who would fight the Taliban and Islamic State—with help from one of Broidy’s companies, Circinus LLC, a defense contractor based in Virginia. Broidy suggested to the president that the deputy commander of UAE’s armed forces come for a meeting with Trump in New York or New Jersey. And when Trump asked Broidy’s opinion of then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Broidy said he should be fired. Two months later, UAE, which had joined Saudi Arabia in an embargo of Qatar that Broidy supported, awarded a $200 million contract to Circinus to perform confidential work, according to Broidy.

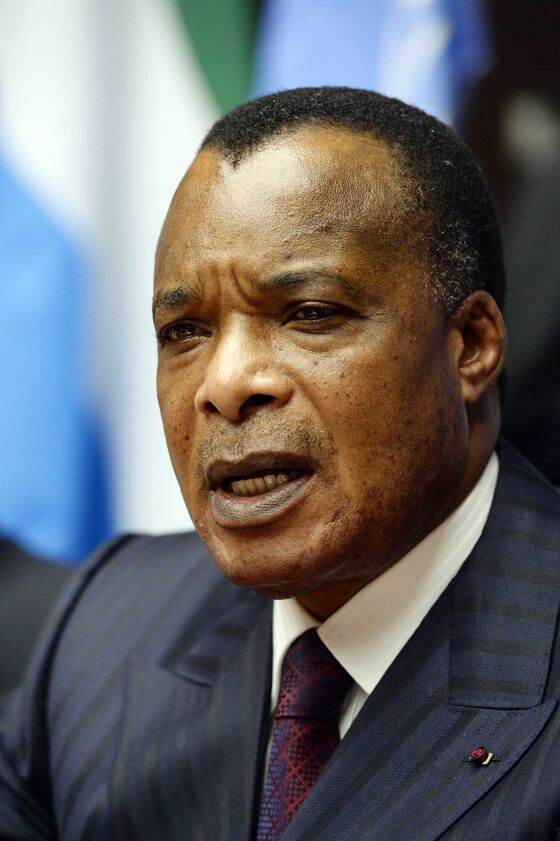

Other documents show that last year, Broidy offered to help a Moscow-based lawyer get Russian companies removed from a U.S. sanctions list, a plan that went nowhere. Broidy and his wife also engaged in contract negotiations to represent a Malaysian businessman known as Jho Low, identified by the U.S. Justice Department as a central figure in the theft of $4.5 billion from Malaysian wealth fund 1MDB. The emails included talking points on why the U.S. should drop its probe. One draft contract called for Rosenzweig’s firm to make $75 million if it succeeded. Broidy also invited Republic of the Congo President Denis Sassou Nguesso to inauguration events, including a candlelight dinner attended by Trump, according to a New York Times story based on the emails; Broidy was courting business from Congo at the time. He also invited Angolan defense officials to inauguration events and dangled a Mar-a-Lago trip while Circinus was pursuing Angolan business. (The African officials didn’t accept the invitations.) It’s unclear if additional details about his Playboy Playmate affair are contained in the hacked emails, but the disclosure appeared to be the final straw for Republicans. Broidy quit as deputy finance chairman of the Republican National Committee after the payment surfaced.

While Broidy has a circumstantial case linking the hack to Qatar, it’s far from ironclad. Security experts found that the hackers used computers based in the U.K. and the Netherlands to hide their tracks, but the ploy didn’t always work. On two occasions, the anonymizing software failed, revealing that the hackers were actually in Doha, the capital of Qatar. And metadata associated with some of the emails suggests that Broidy’s private documents were being rifled by a team of at least two dozen people with sequential user profiles, indicating a robust organizational structure behind the theft.

A California judge said Broidy failed in the early stages of his litigation to pin the hack on Qatar, but the case is continuing. What it may really show is the wisdom of the few Republicans who in 2016 warned that the party should be cautious in how it handled Clinton’s leaked emails, because next time it could be one of them. Broidy says he now has sympathy for anyone who has gone through something similar. So far, few other Republicans, including President Trump, have joined him.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Philips at mphilips3@bloomberg.net, Robert Friedman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.