Business Hates Mexico’s Presidential Front-Runner. And He Doesn’t Care

Business Hates Mexico’s Presidential Front-Runner. And He Doesn’t Care

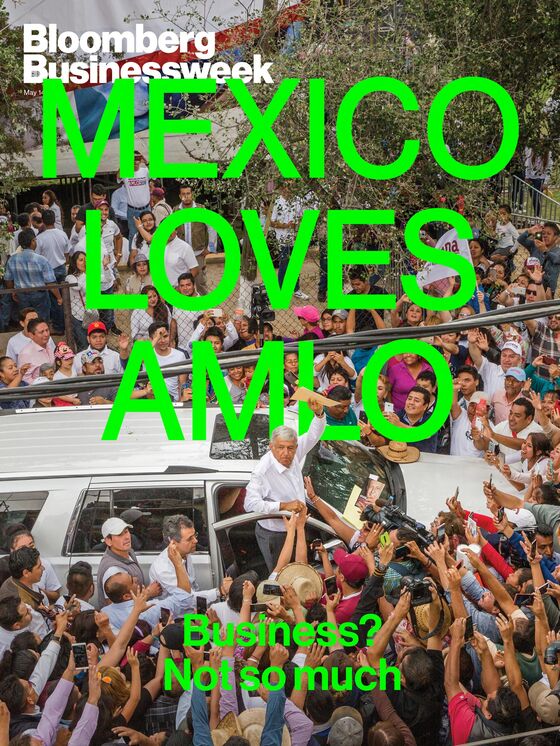

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Andrés Manuel López Obrador, sharing a stage with crates of coconuts and limes, looks out upon a crowd of thousands: a sea of sombreros bobbing in the sun. They’re farmers, mostly—or used to be, before the North American Free Trade Agreement upended the old traditions here in the Mexican heartland. Now, many take whatever jobs they can find and lament that so much corn, Mexico’s iconic national crop, is now imported from the U.S.

López Obrador—or AMLO, as he’s widely known—assures the crowd that their dreams of returning to their farms are within reach. After he wins the presidential election on July 1, he says, he’ll provide them with free fertilizer and cheap fuel, and he’ll establish minimum price guarantees for homegrown crops. The fields here in the central Mexican state of Zacatecas will spring back to life, which will provide people with jobs and, in turn, stem the outward flow of migrants to America. But for this chain of prosperity to kick in, there’s one condition: An electoral deathblow must be struck against the ruling political class, a group López Obrador references in terms this rural audience appreciates.

“Filthy pigs!” he shouts. “Hogs! Swine!”

The contempt that most of Mexico feels toward the established political order might be measured by the rising pitch of the whistles and the jeers, a resentful clamor that the 64-year-old López Obrador—fist raised, sweat beading on his brow—has done his best to provoke and amplify. For decades he built a following throughout Mexico the hard way: staging rallies in every one of the country’s 2,400-plus municipalities, no matter how small, no matter how distant from the centers of power. Now, after two failed presidential bids, he’s emerged as the undisputed front-runner, enjoying an advantage of almost 20 percentage points over his nearest rival in a crowded field.

Earlier this year, despite López Obrador’s commanding lead in the polls, 85 percent of Mexican corporate executives surveyed by Banco Santander SA predicted he would find a way to lose this election. Now their confidence seems to be giving way to apprehension. They fear his brand of populism is fueled by a false nostalgia for simpler times—a mythical era that was never that good to begin with—and they’re afraid he might roll back 25 years of economic modernization. López Obrador doesn’t bother to counter the claims that his victory would represent a large-scale societal upheaval; in fact, he encourages the notion, casting his rise as the most consequential political development here since the Mexican Revolution that began in 1910.

It’s tempting to compare his campaign to Donald Trump’s, though ideologically they’re negative images of each other. Both appeal to a base that dreams of reviving sectors—manufacturing in the U.S., agriculture in Mexico—that were economic backbones broken by globalization. So far, López Obrador’s relationship to the American president is shaping up as a symbiotic one. His campaign, which taps into a proud vein of nationalism, seems to grow stronger every time Trump uses Mexicans as rhetorical cannon fodder.

“We won’t care about threats of a wall,” López Obrador announces, assuring another rally crowd in Zacatecas, one of the states that sends the most migrants to the U.S., that with him in power, they’ll finally achieve equal footing with their neighbors to the north. “Nothing will matter. They’ll be the ones with the problem because our people won’t have to go to the United States, and they won’t have anyone to pick their crops or build their houses. And so we’ll be the ones deciding the conditions.”

Before dueling tuba bands flood the rally with noise, one enthusiastic onlooker raises his voice above the others. He calls out a phrase that has become something of a campaign slogan for López Obrador, a saying with roots in Mexico’s rural past, when people tried to pick their winners in the cockfighting ring. “Ese es mi gallo!” the man shouts. He’s my rooster!

López Obrador’s story begins in Tepetitán, a village of fewer than 1,500 on a river bend in the southern state of Tabasco. His grandparents were campesinos and his parents ran a fabric shop. Boyhood friends recall a kid who loved baseball and whose destiny didn’t look a lot different from theirs. But when he was 15, a murky drama unfolded inside his parents’ store that would become a foundational parable of his career.

Late one afternoon his younger brother, José Ramón, grabbed a pistol and tried to persuade López Obrador to use it to scare an employee of a nearby shoe shop. According to a report by Enrique Krauze, a prominent Mexican historian, López Obrador argued with his brother, trying to persuade him to put away the gun. He had just turned his back on the boy when he heard the bang. His brother had accidentally shot himself, suffering a fatal wound.

He doesn’t say much about the incident today, other than acknowledging that it affected him deeply. Krauze has suggested the tragedy burdened López Obrador with guilt, which he tries to atone for with an almost messianic zeal to change the course of history.

As a young man he became an advocate for Mexico’s indigenous population, and he helped oversee the construction of rudimentary houses and latrines in rural villages. His first foray into electoral politics came in 1976, when he joined the senatorial campaign of a candidate representing the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI. Choosing a PRI affiliation was almost a given; the party maintained a stranglehold on national politics, occupying the presidency from 1929 to 2000. He was quickly appointed a local party head but lasted less than a year—he tried to oversee spending among PRI mayors in Tabasco, and they pushed back. According to a local historian, López Obrador was also advised to tone down his revolutionary rhetoric and was warned, “This isn’t Cuba.”

“There are people in history who have no ideology and adapt to circumstances,” says Geney Torruco, who serves as the official historian of Tabasco’s capital city, Villahermosa. Such people, he says, have almost nothing in common with López Obrador. Rodolfo Lara, his middle school teacher, describes someone whose leftist beliefs have never really changed, even if his method of expressing them has evolved. “He’s matured in the sense that his expressions aren’t as harsh. He invokes ‘love and peace’ whenever they try to corner him. But has he changed his ideology? I don’t think so,” Lara says.

In 1988, López Obrador joined a coalition of leftist parties, ran for governor, and lost by a wide margin, which didn’t stop him from leading protests claiming voter fraud. He lost a bid for governor again in 1994, and this time his complaints of vote-rigging carried more weight. Regulators found evidence of numerous discrepancies at polling stations. He led a caravan of protesters from Tabasco to Mexico City, where he and his followers took over the capital’s main square. The sit-in was eventually broken up, but not before it helped force the resignation of Mexico’s interior minister, who serves as the president’s second-in-command.

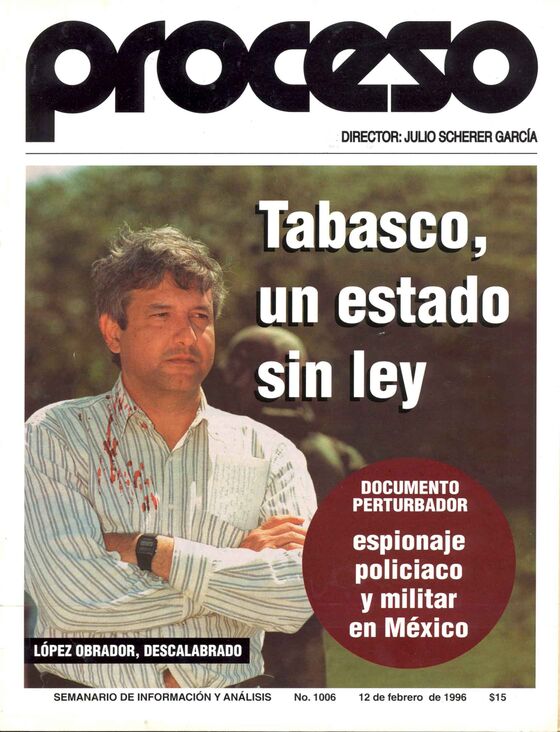

López Obrador now was a presence on the national stage, and his leadership of a string of protests against Pemex, the national oil company, helped him stay there. In 1996, Mexican police tried to remove him from one such blockade. Pictures of him in a blood-soaked shirt graced the cover of a national magazine, reinforcing his standing as one of the country’s most persistent social agitators.

All of this set the stage for his first—and, to date, only—electoral victory. In 2000 he was elected mayor of Mexico City. He instituted a slate of social programs, including monthly pensions for the elderly, and ushered in widespread infrastructure improvements. As his popularity grew, his political opponents closed in on him. Amid accusations that he improperly built a road to a hospital on private land, he was impeached. The case buckled under scrutiny and under pressure from protests that attracted more than 1 million supporters. Mexico’s attorney general, who was widely accused of trying to sabotage López Obrador’s presidential aspirations, was forced out of office. López Obrador ended his term in 2005 with approval ratings hovering around 80 percent.

During his first presidential campaign, as the candidate of the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) in 2006, he was often cast in the media as a member of Latin America’s New Left, a group that included populists such as Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez and Argentina’s Néstor Kirchner. But Mexico’s politics have always been more intricately connected to the country’s northern neighbors than its southern ones, and it narrowly resisted the leftward swing. López Obrador lost to Felipe Calderón by about a half-percentage point. He disputed the results, again alleging fraud and casting himself as a political threat that Mexico’s elite would do anything to destroy. His followers took over tollbooths on federal highways and surrounded the offices of foreign banks, accusing the businesses of conspiring with Calderón to deny him his rightful triumph. López Obrador declared himself the legitimate winner and appointed members to a shadow cabinet. He led another sit-in in downtown Mexico City, and this one lasted more than a month.

By the time he lost his second presidential bid, in 2012, his reputation among rivals was firmly set, and it centers on two dominant traits: a seeming willingness to tear down any institution he believes is biased against his political movement and a bitter reluctance, regardless of the circumstances, to give up.

If the anxiety that López Obrador provokes among Mexico’s political and business leadership has a geographical center, it probably sits somewhere near Monterrey. Many of the country’s most successful international corporations are headquartered in the city, which has been thoroughly transformed during the past 25 years by Nafta. Factories and business parks ring the outskirts, and its roadsides are crowded with chains: Carl’s Jr., 7-Eleven, Walmart. Monterrey isn’t immune to Mexico’s epidemic of cartel violence, but some of the suburbs on the west end of town could be mistaken for upscale neighborhoods in Southern California. The region has the country’s lowest poverty rate and highest formal employment rate, and a per capita income roughly double the national average.

When Trump hectored Carrier Corp. to keep manufacturing jobs at a plant in Indianapolis during the 2016 campaign, those jobs came here anyway, to a sprawling complex of factories and warehouses north of town. And when Trump swore off Oreos because Nabisco started talking about moving out of Chicago, those jobs, too, ended up in the same industrial park.

The development is called Interpuerto Monterrey, a 3,459-acre complex that opened in 2013 and is now home to a dozen companies from the U.S., South Korea, Japan, and Mexico. Its enticements are clear: easy access to Mexico’s two main rail lines, a dedicated customs office, full utility services, a two-hour drive to the border, and a seemingly inexhaustible supply of cheap labor. That said, these can be challenging times. In 2017 the park attracted a little more than half of the $120 million in investment it had forecast that February. Chief Executive Officer Mauricio Garza Kalifa blames it on a “perfect storm” of uncertainty that’s settled over Monterrey. The ongoing Nafta renegotiation is part of it. So is the new U.S. corporate tax plan, which has bitten into Mexico’s competitive advantages. Finally, there’s López Obrador.

“Yes, there is a little bit of worry around what, in reality, he’s actually going to do,” Garza Kalifa says. “Is he going to radically change the course of the country, or will he follow the same general path we’ve been on? Foreign investors seem cautious, waiting to see what’s going to happen.”

Mexico’s domestic investors are also skittish. In Monterrey’s executive suites, there’s a natural antagonism toward López Obrador. Some suspect it’s them he’s talking about when he rails against the “mafia of power.” In February the candidate visited the city and convened a meeting at a Holiday Inn Express, ostensibly to assure the business community that he was willing to work with them. Hundreds crammed into the conference hall, but some who attended say the gathering was notable for who wasn’t there. Jesus Garza, who runs a Monterrey financial company and who previously worked as an economist for Mexico’s central bank and the Ministry of Finance, says many of the city’s biggest business leaders were nowhere to be seen.

Garza managed to snag an invitation from a friend involved with López Obrador’s political party, Morena. Like many others here, he was keen to hear what López Obrador had to say about the energy sector. For most of a century, Pemex dominated the industry. But in 2013 the government opened the oil and gas business to foreign companies. The idea that López Obrador might nullify many of those contracts, undermining the sector’s privatization plan, tops the list of concerns among many business leaders.

López Obrador has said he has no plans to nullify any of the contracts, which are valued at as much as $153 billion—unless reviews prove individual contracts were tainted by corruption. A week before that February meeting, one of López Obrador’s economic advisers publicly assured investors that they shouldn’t be scared and that the contracts would be respected and protected. Even if López Obrador wanted to roll back the reform, he’d need the support of two-thirds of Congress. But when López Obrador got to Monterrey, Garza says, the candidate seemed to leave the door open to a massive overhaul of the sector. “I think deep down inside he doesn’t believe in the energy reform agenda that was established by the current administration,” Garza says. “And with power, I think he would reverse it if he got the chance.”

That sort of distrust casts a shadow over almost everything López Obrador promises. Some warn that his history of disputing election results is a sign of authoritarian impulses, and they warn he might bring a Hugo Chávez-style socialism to the country. That typically means government spending. López Obrador and his pick for finance minister, Carlos Urzua, however, have pledged to reduce the budget deficit, to respect the autonomy of the central bank, and to keep the peso floating freely. The savings they’ll reap from eliminating corruption and graft, they say, will keep the government flush. “We are more centrist than Lula,” says Urzua, referring to Brazil’s former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, another leftist who campaigned on social reform and who ultimately surprised investors with business-friendly policies.

Not everyone buys the sales pitch, of course. Citigroup Inc.’s Mexico economist Sergio Luna recently warned clients that López Obrador would “eventually generate macroeconomic inconsistencies in terms of monetary, fiscal, and commercial policy.” He sees inflation rising and the deficit widening.

It doesn’t help that the candidate himself often contradicts the same advisers who defend him as a fiscal pragmatist who won’t do anything drastic. At a February rally in Puebla state, López Obrador vowed to his supporters that he would never allow Mexican crude to return to the hands of foreigners—after his advisers had said he would never try to nationalize the oil industry. At another rally he vowed to end gasolinazos, or surges in gasoline prices, by freezing prices in real terms—though his team later insisted that what he really meant was that he’d cut fuel taxes. More recently he said he may seek to reform the oil industry in the second half of his administration.

The current administration of Enrique Peña Nieto instituted free-market reforms to the energy and fiscal sectors under a plan called the Pacto por México. Over time, they’ve proved deeply unpopular, as has the president, who’s been saddled with approval ratings as low as 12 percent. Corruption scandals hastened his fall from grace.

The higher López Obrador rises in the polls, the more willing he seems to drop all pretense of appeasing business leaders. Within the larger context of Mexico’s problems—spiraling violence, rampant corruption, endemic poverty—their anxieties can seem beside the point, and Monterrey begins to look like a tiny island in a very big sea.

The first of three planned presidential debates was held in late April, and the evening’s broadly stated theme—governance and politics—quickly narrowed to focus on Mexico’s two most pressing preoccupations: violence and the impunity that almost always accompanies it.

Last year was the deadliest in Mexico’s history, with almost 30,000 murders. This year things are even worse, with homicides jumping 20 percent in the first three months. Turf battles among the drug cartels rage across the country, and daily news reports are dense with assassinations and dismemberments. In contrast to the U.S., where about two-thirds of homicides result in arrests and indictments, about 95 percent of all crimes in Mexico—and more than 98 percent of homicides—remain unsolved.

One of the five presidential candidates, Jaime Rodríguez, the independent governor of Nuevo León, suggested he’d combat crime and corruption by cutting off the hands of thieves. When a debate moderator asked if he was speaking figuratively, he assured her he was not.

López Obrador’s own proposal of amnesty for certain criminals as an attempt to start a dialogue and stop the cycles of violence—an idea that previously had been pounced upon by some of his critics as irresponsibly unhinged—seemed relatively conventional. A political truism seemed to be emerging from all of this: When important governmental institutions are so comprehensively broken, the politics of continuity becomes untenable, and the extremes are pulled into the center. How could a candidate be criticized as too radical if radical change is desperately needed?

López Obrador’s closest competitor in the race is Ricardo Anaya, who represents a coalition of parties and generally casts himself as pro-business. The PRI’s Jose Antonio Meade has struggled to distance himself from Peña Nieto and is running a distant third. Rodriguez and Margarita Zavala, the wife of former President Calderón, round out the ballot. As the most vocal proponent of comprehensive change in the race, López Obrador seemed both galvanized and relaxed at this debate. In 2006 he infamously told incumbent President Vicente Fox at a campaign event to “¡Cállate, chachalaca!” (“Shut up, you noisy bird!”). Now he appeared subdued, even withdrawn. At one point he marveled at his lead in the polls and suggested there was almost no way he could lose.

“Something terrible would have to happen,” he said.

A week later he returned to Monterrey to attend a forum at the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education. Known as Tec, it’s generally considered the best business school in Latin America. Tec is the alma mater of many of López Obrador’s adversaries within the country’s business elite. Figuratively, and in some cases literally, he had come to speak to their children.

About 1,800 students packed into an auditorium, where López Obrador relaxed in an armchair, serenely answering dozens of questions about everything: the death penalty (he opposes it), euthanasia (he supports it), the idea of pensions for former presidents (he’ll abolish it), gender equality (he’ll respect it). When he dropped a casual reference to how the powers that be unfairly thwarted his first presidential run, he was rewarded with applause. A former student named Manuel Toledo took to Twitter after the event and observed, “As an alumnus of this institution, I must admit that I never in my life expected to hear the students of Tec de Monterrey applaud AMLO after he stated (with customary pride) about 2006, ‘With all due respect, they stole the presidency.’”

The millions who dwell in Mexico’s impoverished countryside remain his ever-reliable base, the ones he’ll always be able to connect to with an unaffected ease. But it’s the residents of Mexico’s north, in cities such as Monterrey, who will determine whether this year is different for him from 2006 or 2012.

When he concluded his remarks, López Obrador waved to the students and slipped a Tec jersey over his shirt and tie. He exited the stage to chants of “Presidente, presidente, presidente!”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Ferrara at dferrara5@bloomberg.net, Jim Aley

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.