The $94 Billion Mystery: What Will Be Left of HNA’s Empire?

The $94 Billion Mystery: What Will Be Left of HNA’s Empire?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As HNA Group Co. rose from provincial obscurity to becoming perhaps China’s most acquisitive global company, its executives made no secret of their desire to play in the big leagues. It appears they got their wish—just not in the way they wanted.

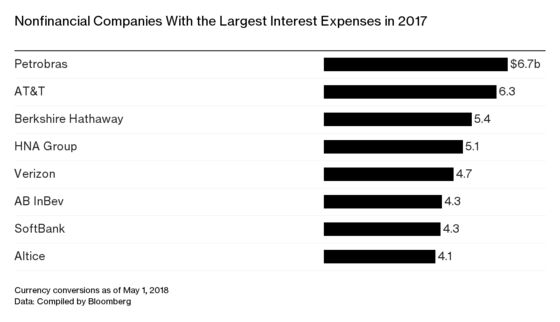

An annual report released in late April revealed that HNA spent more on interest than any nonfinancial company in Asia last year, a $5 billion bill that represented a more than 50 percent increase from the year before. A sprawling conglomerate with roots in a middling regional airline that was founded on China’s sleepy, tropical Hainan Island, HNA carried a total of $94 billion in debt at the end of 2017, a hangover from a dizzying global acquisition spree that made it the proud owner of a huge trove of trophy real estate and blue-chip corporate stakes.

The figures are a stark illustration of the potential peril faced by HNA, which as recently as a year ago was feeling confident enough to fete its co-founder Chen Feng with a birthday bash at Paris’s Petit Palais—just after becoming the largest shareholder in Deutsche Bank AG, with a stake then worth €3.4 billion ($4.1 billion). While a series of successful asset sales this year has given it breathing room, HNA still needs to unwind some of its splashiest purchases to reach a sustainable financial footing—a humiliating retreat for a company once eager to be seen on the grandest of stages.

“At the end of the day, it’s a cash-flow issue,” says Victor Shih, a professor of political economy at the University of California at San Diego, who studies the Chinese financial sector. “HNA actually had higher interest payments than net profit, which is very dangerous.”

An HNA representative says the company continues to manage its operations in line with its strategic and financial needs, as it stays focused on the core areas of tourism, logistics, and financial services.

Still, the company’s difficulties have led to some rapid reversals in strategy. Bloomberg reported in late April that HNA was in talks with SL Green Realty Corp. to sell at least part of 245 Park Ave., the prestigious Manhattan skyscraper it bought for $2.21 billion in 2017—believed to be among the richest prices ever paid for a New York tower. Since the beginning of this year, the Chinese company has reversed a commitment to maintain its Deutsche Bank stake, exited a $6.5 billion investment in the Hilton Hotels & Resorts chain (cashing out for $8.5 billion), and sold off what was to be a showpiece development on the site of Hong Kong’s decommissioned Kai Tak Airport. The distress is playing out in much smaller ways, too: Employees have been told to limit stationery expenses to 20 yuan ($3.16) a month, and its airlines earlier this year fell behind on fuel bills.

Throughout its breakneck growth, HNA explicitly presented itself as the new face of Chinese capitalism, a symbol of the country’s rising economic might that would harmoniously combine Asian capital with Western businesses. HNA’s sudden retrenchment risks making the company a symbol of something else instead: the fact that Chinese companies remain much less predictable than their counterparts in Europe and North America.

“China’s apparently strong economic growth seems unable to shake these uncertainties,” says Ja Ian Chong, an associate professor of political science at the National University of Singapore. “The thing about China, and Chinese firms like HNA, is that no one is entirely sure what will come next.”

The woes began last summer, when Chinese regulators asked banks to disclose exposures to HNA and four other highly acquisitive companies including Anbang Insurance Group Co., which has since been seized by the government. The requests to lenders signaled decreasing tolerance in Beijing for unfettered dealmaking. Some state-owned Chinese banks stopped extending loans to HNA, while global giants including HSBC Holdings Plc and Bank of America Corp. began steering clear of the group.

Although HNA isn’t publicly traded, the annual report it just released contains selective financial information that reveals how overstretched the banks’ pullback has left the company. Overall debt rose 21 percent in 2017, according to the report, with short-term borrowing climbing by 25 percent, to about $30.3 billion. Total debt amounted to about 20 times HNA’s earnings before interest and taxes, a ratio far worse than most global nonfinancial companies of comparable size.

Nonetheless, HNA, which Chen co-founded in the 1990s, counting George Soros among its early investors, isn’t at risk of immediate catastrophe. At the start of 2018, according to people familiar with the matter, it told creditors it would sell about $16 billion in assets in the first half to lighten its balance sheet. Happily for the banks that financed its rise, HNA is already nearing that goal, thanks largely to the Hilton sale.

“It’s too early to say what will ultimately happen to HNA and whether it will survive in some much smaller form,” says Nigel Stevenson, an analyst in Hong Kong at GMT Research Ltd. While initial asset sales have yielded decent prices, he says, “the easiest to sell will be disposed of first.”

What sets HNA apart from the countless companies that have overextended themselves is its opaque ownership structure. Officially HNA is controlled by its employees and a pair of charities named for Cihang, a mythical Chinese deity—one based in China and the other in New York. Yet the company has been dogged for years by rumors of financial ties to senior Communist Party leaders, in particular Wang Qishan, who became China’s vice president in March. (HNA denies this and has sued the exiled Chinese businessman making this claim.)

Questions about ownership have caused other problems. In December, Ness Technologies SARL sued two HNA units, claiming HNA provided “false and inconsistent information about its ownership” to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, a federal body that vets acquisitions by non-U.S. companies for security concerns.

As a result, Ness claimed, a planned $325 million acquisition by HNA’s Pactera unit of a company Ness controlled fell apart. HNA, which denies providing false information, is contesting the suit. The deal was one of several HNA acquisitions that have foundered in the CFIUS process. The Chinese company’s acquisition of SkyBridge Capital, the New York investment firm founded by Anthony Scaramucci, was called off on April 30 after months awaiting CFIUS approval.

And there are indications some companies find it perplexing to be in HNA’s orbit. A member of Deutsche Bank’s managing board, who asked not to be identified discussing a private matter, says the bank has found the experience of having HNA as a big shareholder confusing. The HNA representatives delegated to deal with the bank change frequently, the executive says, leaving it unsure who it’s dealing with, who stands behind them, or what the ultimate goal is for the stake. HNA controls about 8 percent of the bank’s shares, down from just under 10 percent. Deutsche Bank declined to comment. HNA says it has a strong relationship with the bank’s board.

HNA has never claimed to be a typical company. New employees receive a list of 10 values that they’re expected to espouse, inspired by Buddhist ideals, including humility, benevolence, and perseverance. As a reminder of the first, a photo of Chen serving coffee and tea on one of the first flights of Hainan Airlines is displayed prominently at HNA headquarters. Employees are asked for total commitment; as the company grew, it encouraged staff to put their savings into HNA-backed investment products.

Nowhere is the scale of HNA’s ambition, and the risks of its collapse, more apparent than on Hainan, which might as well be called HNA Island. The company operates three of the province’s airports, and Hainan Airlines carries about half of visitors to what local officials pitch as China’s answer to Hawaii. In the center of Haikou, the provincial capital, is an HNA-owned shopping complex consisting of 12 gleaming buildings, each named for a sign of the zodiac, atop an underground mall. Across the street is HNA’s headquarters, a 31-story building that resembles a seated Buddha.

Nearby, HNA is developing a pair of hotel and condominium towers, one rising 94 stories. They’ll rival skyscrapers in Shanghai and Hong Kong, with work continuing despite the company’s high-wire act. The buildings are the centerpiece of a project to convert an old airstrip into a business district half the size of New York’s Central Park and are designed to resemble another Buddhist symbol, the lotus flower, when viewed from above—say, through the window of a Hainan Airlines 787. There’s just one problem: The project is almost certainly too big for the slimmed-down HNA, and it’s bringing in new backers. —With Christian Baumgaertel

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.