‘Whatever It Takes’ Only Works If Countries Coordinate

‘Whatever It Takes’ Only Works If Countries Coordinate

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- After a halting start, governments and central banks have finally been coming to grips with the economic consequences of the coronavirus outbreak. The Covid-19 disease is more than a health crisis. What seemed like an alarmist scenario a month ago—a global recession—now appears a certainty. And the extreme measures needed to limit infections may intensify the slump.

Maurice Obstfeld, the International Monetary Fund’s former chief economist, says you’d have to be optimistic to believe we’re experiencing something akin to the recession caused by the financial crisis, when global output in 2009 shrank 0.1%, according to IMF data. As governments restrict travel and close restaurants while manufacturers prepare for temporary shutdowns, major economies are now experiencing a “hard stop,” which could inflict a toll that may be closer to the 9% contraction Greece endured at the height of its sovereign debt crisis, he says. “We are seeing a collapse of economic activity as countries try to get a handle on this disease,” Obstfeld says, pointing to the plunge in industrial production and consumption in China as evidence of what lies ahead for Europe and the U.S.

The extent of the damage, he says, will depend in large part on the scope and duration of the outbreak. But a lot relies on governments acting in unison to roll out aggressive measures that ease the pain for big businesses ( think airlines) as well as the little guy (your neighborhood bartender). At the same time, central banks need to do everything in their power to prevent what began as a health crisis from morphing into a financial meltdown.

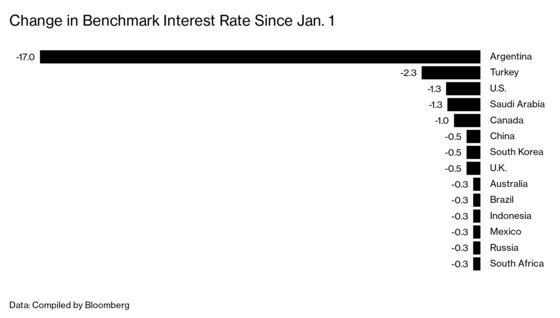

After some foot-dragging, policymakers in Europe and the U.S. are swinging into action. Central banks have cut rates and enacted measures to ensure stressed markets continue to function. Following a March 16 videoconference call, the leaders of the Group of Seven nations vowed to do “whatever is necessary” to protect lives as well as livelihoods.

The statement echoed former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s 2012 vow, in the throes of the European debt crisis, to do “whatever it takes” to preserve the euro. But the G-7 declaration, which was replete with grand promises rather than tangible actions, didn’t spark a relief rally the way Draghi’s pledge did. The Dow Jones Industrial Average closed down 13% on March 16, as U.S. markets recorded their biggest single-day fall since the 1987 crash.

That the G-7 statement came just hours after the U.S. Federal Reserve announced its second emergency rate cut in 12 days raises an ominous question: What if this time whatever it takes is not enough?

During the global financial crisis, much of the credit for preventing a slip from recession into depression went to the decisive actions of groupings such as the G-7 and G-20, which repeatedly signaled their resolve to eschew protectionism and beggar-thy-neighbor policies like currency devaluations. More than a decade later, it’s plain to see that the bonds among historical allies have been frayed by the trade wars and heightened mistrust—which risks taking the response to the present crisis down a dangerous nationalist path.

By calling SARS-CoV-2 a “Chinese virus” and abruptly imposing travel restrictions on visitors from China and Europe, President Trump has further strained those relationships. Chinese officials have complained of unfair discrimination and ordered the expulsion of American journalists. The Europeans, who were irritated that Washington hadn’t consulted with them on the travel ban, introduced their own restrictions a few days later, and a raft of other countries including Canada have followed suit.

Another factor working against a concerted effort is that the U.S.—and Trump, a self-proclaimed anti-globalist—presently holds the rotating presidency of the G-7. It doesn’t help either that Saudi Arabia, which is at the helm of the G-20, has decided to wage a destabilizing price war against U.S. shale oil producers. “Right now I don’t think—given the Trump presidency—anyone imagines the G-7 or the G-20 as an effective coordinating device for a response to this crisis,” says Adam Tooze, a Columbia University economic historian and the author of Crashed, an account of the 2008 crisis. “The only way to put this is it’s quite disillusioning.”

It’s not just the Americans and the Saudis who could undermine attempts at collective action. In what Obstfeld calls a “Europe First” moment, the European Union recently banned exports of face masks and other protective gear to countries outside the bloc. Although the move was meant to ease the flow of precious supplies within the EU, it was also evidence of something potentially more corrosive. “It’s not surprising that after three years of President Trump tearing down international cooperation the Europeans would not have a lot of trust in any sort of U.S. leadership role or be willing to put their interests at the mercy of international cooperation,” says Obstfeld, who’s now at the University of California at Berkeley. “But it’s really sad, and it doesn’t bode well for the future and trust between countries once we as individual nations get through this panic.”

There are signs that such tussling may be only just beginning. Die Welt am Sonntag and other German media reported on May 15 that the Trump administration had sought to acquire a German company developing a coronavirus treatment to secure its sole use for the U.S., prompting an intervention by Berlin. Tooze and others see in that a portent of a bigger fight to come, one that will likely take the trade restrictions from the realm of safety equipment into the far more challenging arena of intellectual property and medicines that pharmaceutical companies are racing to develop.

“The major players are acting as if their interests are not aligned,” says Daniel Drezner, a Tufts University political scientist. That is one of the major ways in which this crisis is different from 2008, says Drezner, author of The System Worked: How the World Stopped Another Great Depression.

Then, national interests were both interlinked by globalization and aligned in stopping a meltdown of the financial system. The economic model being tested—free-market liberalism—was also not facing the same assault from populist alternatives such as Trump’s “America First” brand of capitalism.

Although many expect the current economic shock to be short and sharp, there are also concerns that it may have other, longer-lasting consequences. At the Institute of International Finance, chief economist Robin Brooks and his team have been tracking huge outflows of money from emerging markets that could trigger old-fashioned balance-of-payments crises similar to the ones that engulfed Mexico and most of Asia in the 1990s.

Brooks also frets that governments in developed economies are moving too tentatively and on parallel tracks, which will dilute the potency of measures to offset the downturn. “We need with greater urgency globally a fiscal response, and it needs to be coordinated,” he says. “There’s no reasons for delay now. We know this thing is coming, and it is coming hard.”

In December 2008 the IMF’s managing director, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, pushed for a coordinated global effort by governments to spend an additional 2% of global gross domestic product, or $1.2 trillion, and economists increasingly say something of the same order is needed now.

As of March 17 governments had announced stimulus measures adding up to just under $3 trillion, or 3% of global GDP. Included in that total is a $1.3 trillion package proposed by the Trump administration that will still have to get through a divided Congress in an election year.

While financial markets have been underwhelmed by the response so far, it’s worth remembering that the U.S. had been in recession for almost a year by the time the G-20 nations convened in Washington in November 2008 to coordinate policies in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. “If we had that amount of time with the coronavirus, we’d feel pretty lucky,” says Tooze. Today, “the sheer pace is staggering.”

Obstfeld says the sudden stop in economic activity hitting Europe and the U.S. now looks a lot like an accelerated version of what happens in a classic emerging-market crisis when countries abruptly lose access to capital markets. Which is why he worries the world’s biggest economies may be about to experience a Greece-like shock, with all its consequences, from sharply rising inequality to a realignment of the political order. An inadequate policy response—with less fiscal stimulus than needed and the erection of more barriers to trade—would mean a contraction that could be deeper and longer than the one the U.S. suffered in the Great Recession. An adequate one may mean a rapid recovery and avoiding the economic doldrums that followed the last crisis. “That,” Obstfeld says, “would require a lot more coordination between countries.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.