A Dead Doctor, the Trauma of Sexual Abuse, and a Bank in Denial

The ‘Dirty Doctor’ of Newcastle Still Haunts Former Barclays Employees

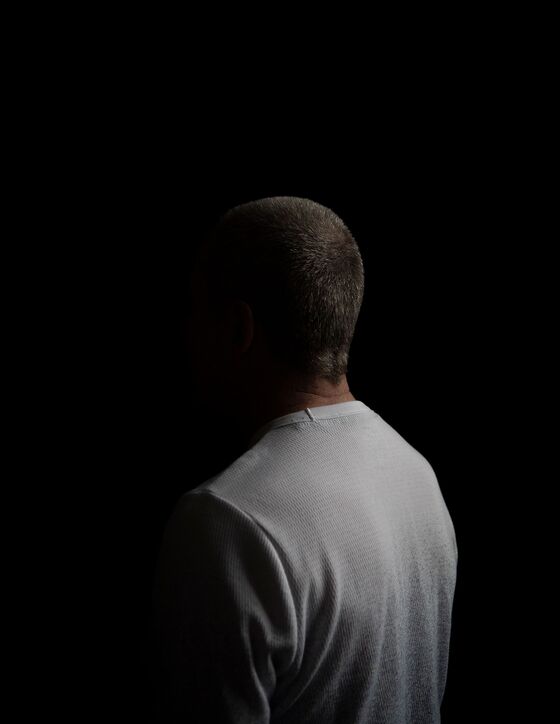

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It was a beautiful summer day in Newcastle, near England’s northeast coast, and James was practically skipping to a doctor’s appointment. He was small, tough, alone, and 16. He crossed a leafy street, spotted the address, and knocked. The woman who answered let him in and pointed to a flight of stairs. He climbed to the top and saw Gordon Bates.

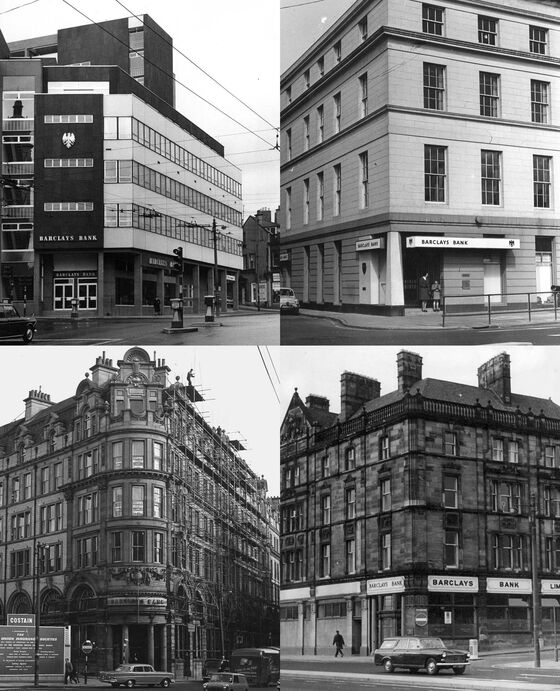

The year was 1976, and James had been sent to the house by Barclays. He needed to pass a medical exam before he could start a job on the bottom rung at one of the bank’s many branches in and around Newcastle. The city, once an Industrial Revolution center of coal mining and shipbuilding, had long been in decline, and Barclays, one of the U.K.’s biggest banks, was a rare ticket to success, stability, and a pension. It liked hiring local teenagers as tellers and office assistants. All they needed were satisfactory grades, enough charm to get through an interview, and a visit to the doctor.

James entered a small room, and Bates closed the door. “What I found very strange, having come from a very beautiful blue-sky sunny day, is it was very dark,” James recalls. (The name is a pseudonym, in keeping with a court order.) Bates checked his ears, eyes, and teeth. “He told me to get to the dentist quickly—if I didn’t it would cause me serious problems,” James says. Bates started feeling his arms and legs. “I’m just thinking, What’s this guy doing? Then, to my undying shame, he asked me to drop my pants.”

Bates placed his hand on James’s testicles and told him to cough. His hand lingered. “Then he asked me to go over to this little bed where he asked me to bend over.” Bates put his finger inside James, “not very far, but enough to make me yelp,” then asked him to lie down and grabbed his penis.

James dressed and left, stepping back into the sunshine. He remembers darting down the bus route, running from one stop to the next, making it a few miles before getting a ride home across the river. He told his mother something had gone wrong, though he didn’t say exactly what, and his parents comforted him. “It was probably those two that enabled me to put it in the back of my mind,” he says.

He got the job and spent more than three decades with Barclays Plc, moving around and reaching a senior back-office position. In about 2014 he was listening to his car radio when he heard the name Gordon Bates. Authorities were looking into claims that the doctor, who’d died half a decade before, had abused young women and men sent to his house by Barclays. James pulled over and collected himself. Then he called the police.

He eventually joined more than 120 people, some as young as 15 when Barclays sent them to Bates, in a lawsuit seeking damages from the bank. Most who’ve come forward are women. The claimants, as plaintiffs in Britain are called, typically say the doctor groped or penetrated them with his fingers during pre-employment medical exams from about 1969 to 1984. Several of them reported the doctor to their managers as early as the late 1970s, according to claims made in court records obtained by Bloomberg Businessweek, though Barclays disputes their allegations.

The suit has drawn one of the world’s top banks into a reckoning over sexual abuse and who should pay for it. Barclays has defended itself in court by saying it isn’t responsible for whatever the doctor might have done because he wasn’t an employee. In 2017 a judge sided with the claimants. The bank appealed and lost again. Now it’s taking its case to the U.K. Supreme Court, where it will argue against James and the others on Nov. 28.

The fight isn’t only about what happened decades ago in that house in Newcastle, or even who knew about it. It’s also about this: When do corporations have to take responsibility for the people who work for them? The answer could reverberate through today’s gig economy.

A spokeswoman for Barclays wouldn’t comment on the case but said the bank sympathizes with the claimants. James expects more from the place where he spent so much of his life. “If you cut me in half, I had Barclays within the inside of my body,” he says. “I can be quite vindictive, and I think, Barclays, I want you to pay for this.”

Bates was the son of a Newcastle physician. He became a general practitioner himself by the mid-1950s and a few years later started doing medical exams for prospective emigrants to Australia and Canada. He also vetted job applicants for a South African mining company, reviewed pension applications, worked for a local hospital, and wrote a “Dear Doctor” column in the newspaper, according to legal filings. His wife, son, and daughter were sometimes home while he was upstairs with patients. Photos of him on a genealogy website show a pale man with big ears and a thin smile who wore spectacles and kept his trousers high.

When Bates started doing exams for Barclays, his son, Nigel, told the court, they took up just a small portion of his time. The bank has said in legal filings that the purpose of the exams was to make sure employees were fit to work and get life insurance. The system in Newcastle was smooth: After applicants made it through job interviews, the bank sent letters telling them they had to get examined by Bates. Barclays made the appointments, told the applicants where he lived and when to go, and paid Bates a per-patient fee. The bank called him “our doctor,” one judge noted. Sometimes Barclays sent him existing employees, but most were unchaperoned teenagers applying for jobs.

For each patient, Bates filled in a form called the Barclays Confidential Medical Report, which asked for details including height, weight, and medical history; it also asked about abnormalities of the heart, lungs, nerves, and “genito-urinary system,” and about menstruation and miscarriage. In one sample report sent to the court, Bates had this to say about a 16-year-old: “Delay in onset of puberty. Normal development of secondary sexual characters. Normal external genitalia.”

British medical guidebooks were hazy at the time about what constituted abuse, warning broadly against serious misconduct without specifying what that entailed. Today, Britain’s General Medical Council tells doctors to get permission for genital exams, offer chaperones, allow questions, warn about discomfort, provide privacy for undressing, and keep patients covered when possible. Bates died before the council codified those rules, and it says it has no records of complaints about him.

More than half a dozen employees and their families told the bank Bates had crossed the line, according to allegations in a court document asking claimants to list reports of abuse. Barclays allegedly ignored them. In the late 1970s a woman told two managers at the branch on Collingwood Street that Bates had done “horrible and disgusting” things. The managers told her no one had complained about him before. In 1980 the mother of another employee complained to a Barclays human resources manager about her daughter’s exam. A year later, another employee’s mother called the bank and said Bates had asked her daughter to strip, telling her, “That’s a pretty bra. Now take it off.” The employee who took the call said the bank had never heard anything like that before. Around the same time, three other people complained to a supervisor at the High Heaton branch, who relayed the reports to the regional office. Two years later, a man complained about the doctor to a manager at another branch.

Barclays has said in a court filing that it first learned of the assault claims in 2013, and a lawyer for the bank later told a judge it hadn’t ignored complaints. When asked about the earlier reports of abuse, a spokeswoman for Barclays said the bank wouldn’t answer questions before the Supreme Court’s decision comes down. She added: “We were very concerned to learn of the allegations in relation to Dr. Bates.”

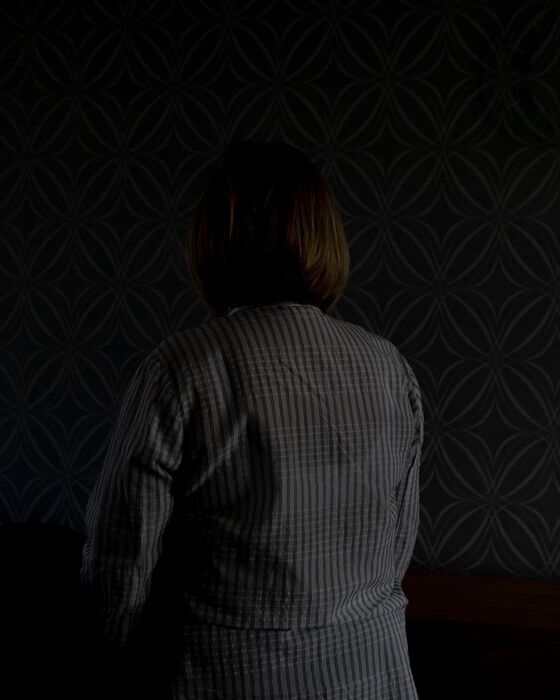

Employees at Newcastle-area branches who’d seen Bates would sometimes raise their experiences with one another. “You’d be working late and somebody would bring up the conversation,” says Anne, who saw Bates in 1977, when she was 16. (Anne is also a pseudonym.) “It was like, ‘You had the medical? With the dirty doctor?’ ” The question would make her shiver. “You could tell people wanted to talk, wanted to open up, but ‘ashamed’ is probably the word.”

At Anne’s appointment, Bates asked her to remove her T-shirt and bra, then began examining her eyes and ears as she stood uncovered. She indicated that she wanted to put her shirt back on. “No, it’s fine,” she recalls Bates telling her.

“I can remember it, thinking: This is not right,” she says. “Why do I need this? I want to work in a bank.” She looked at the road outside the window and held her arms to her bare chest. “Don’t worry,” she says Bates told her. “You can see out, but nobody can see in.” He told her to lie down and face the wall. Then he put his hand inside her underwear and groped her. “It’s OK,” he said. Her mind went blank.

Anne didn’t tell anyone what had happened for years—not a friend who’d also just seen Bates or the man she married, even though he also worked for Barclays and had seen the doctor. Her husband still doesn’t like to talk about his exam, she says.

Barclays sent patients to Bates until he began preparing for retirement in the mid-1980s. Around 1989, the bank stopped requiring the exams altogether. It took another few decades, after abuse allegations against BBC television personality Jimmy Savile became national news, for a woman who’d worked for the bank to tell the police about the doctor. The investigation began in 2013, four years after Bates’s death at age 83. Anne was still working at Barclays when a colleague got a letter from the bank requesting information about Bates and showed it to her. She called human resources, and police came to her house. “I had forgotten how much I could remember,” she says.

She also finally talked about the doctor with the friend who’d started at Barclays around the same time. It turned out Bates had used the line about the window on both of them. “He said exactly the same thing to her. It was daft,” Anne says.

After a nine-month investigation, police concluded that Bates had committed 48 criminal acts and conducted 77 additional inappropriate exams. Had Bates been alive, they told reporters, they would have pursued a criminal case against him.

Some of the people Barclays had sent to Bates were by then talking to lawyers. Richard Scorer, the Manchester-based head of the abuse team at law firm Slater & Gordon, now represents 26 of them. When he was younger, Scorer was part of a generation of attorneys who pushed courts to hold big institutions accountable for sexual abuse by people who worked for them. Some of his first clients accused a Catholic priest named Michael Hill of sexually assaulting them when they were boys. In cases like that one, the church argued that priests weren’t employees, or that they’d been acting outside the scope of their roles. “The courts were presented with a Catholic Church trying to evade liability by saying it doesn’t employ these people,” Scorer says. Hill was sentenced to two different prison terms, and the church settled the civil suit.

The court records obtained by Businessweek show Barclays made a similar argument when it faced off against Bates’s former patients in a London courtroom in 2017. Representing the bank was Edward Peter Lawless Faulks, a House of Lords member also known as Baron Faulks of Donnington in the Royal County of Berkshire. He was up against Elizabeth-Anne Gumbel, whose clients include women who’ve accused film producer Harvey Weinstein of abuse.

In presenting its case, the bank neither admitted nor denied that Bates had abused any incoming employees. Instead, it argued that it can’t be responsible—or, in the language of the law, vicariously liable—for harm done to people who weren’t yet employees by someone who was never one himself. Faulks told the court Bates was an independent contractor for Barclays who also did exams for other clients, including the mining company. “All they were doing,” he said of the bank, “and there is no suggestion for our purposes that they were wrong to do so, was asking these claimants to be examined by a doctor.”

Gumbel tried to best Barclays by structuring her argument around a 2016 British Supreme Court decision, Cox v. Ministry of Justice. The case had been brought by a penitentiary kitchen manager injured by a sack of rice that a prison worker had accidentally dropped on her. Finding in the woman’s favor, a judge explained that a company or institution can be liable for harm done by workers who were doing something important to its business and acting on its behalf, as long as the institution created the risk by bringing them on and had control over them.

Bates’s work for Barclays fit smoothly into that standard, Gumbel argued. The doctor, she said, had done important work for the company by helping it staff branches with young workers, and Barclays had created the risk by giving Bates those medical forms and sending prospective employees his way. The harm had taken place, she pointed out, while Bates was seeing them for the bank. And, she said, “They believed that there was not much they could do about it. ... Although they are about to be employed by the bank, they are in fact still children.”

The judge sided with the claimants, ruling that they could hold Barclays liable for any proven assaults. The bank appealed, and in 2018 the claimants won a unanimous decision. Barclays’ last chance to win a dismissal on the issue of responsibility will be the late-November Supreme Court hearing.

The court’s decision could have implications for Britain’s mushrooming gig economy, which includes more than 4 million workers. In cases in the U.K. and around the world, Uber Technologies Inc. and other multibillion-dollar companies have avoided the costs of a traditional workforce by claiming that they’re platforms for freelancers rather than employers. What links the fights is the question of how much responsibility companies have for the people who work for them. If Barclays loses in the Supreme Court, it could put other companies operating in the U.K. on the hook for harm caused by contractors—exactly what corporations such as Uber are fighting to avoid.

Bates is buried in a graveyard not far from Hadrian’s Wall, which once marked the Roman Empire’s northern border. It’s a beautiful rural spot near a babbling stream on the edge of a hamlet. “A devoted husband and father who brightened up our lives,” his tombstone says.

Bates’s son, Nigel, worked at Barclays for 32 years, according to court testimony. Contacted by email, Nigel wrote: “I have always declined to speak to the English press about the astonishing allegations. I will give it some thought over the next few days, talk it over with the family.” He later followed up to say he wouldn’t comment.

Many former Barclays employees in Newcastle remain fond of the bank. The city has its own chapter of the Spread Eagle Club (named for the company’s logo), a group of gray-haired retirees and their husbands and wives who take blurry bowling pictures, brag about home-knitted sweaters, and poke fun at each other’s naps. Some of the old Barclays branches have now closed; the Collingwood branch, a soaring, ornate space, houses a bar called Revolution. The rest of the city is changing, too. Hundreds of millions of pounds have been spent redeveloping areas long littered with derelict warehouses and crumbling quays. Rough Guides named Newcastle one of the best places in the world to visit in 2018.

Sitting at a cafe in the Quayside neighborhood, James is reminiscing about all the good that came of his time at Barclays. Now a grandfather in his late 50s, he looks slim and athletic, with close-cropped gray hair and shining eyes. “A job with Barclays was seen as a job for life, and a better life at that,” he says. “My friends who worked in the shipyards and in manufacturing have been in and out of work their whole lives.”

He still feels ashamed about what Bates did to him. “It’s made me challenge more,” he says, “resulted in me not being as trustful.” The bank’s fight against the claimants infuriates him, and he brings up an incident at the very top of the bank to suggest Barclays has a pattern of brushing off complaints. In 2018, Chief Executive Officer Jes Staley was fined for his efforts to uncover the identity of someone who’d written a complaint letter about him to the bank’s board. Staley “tried to find out who the whistleblower was,” James says, “and I’m just thinking, Come on, guys. Listen!” He was also angry to learn that Staley’s ties with Jeffrey Epstein, which dated to a business relationship at a previous job, persisted even after the disgraced millionaire pleaded guilty to procuring a minor for prostitution. (Barclays has said Staley never paid Epstein any advisory fees.)

Even if the Supreme Court rules against the bank in the Bates case, there’s no guarantee it will have to pay. If Barclays is found responsible, there could be a second fight over the alleged assaults before any damages are awarded. British courts usually allow a window of three years for suits like this one, and the bank has already told a judge it will resist any efforts by the claimants to win an exception. Scorer, the lawyer, says he hopes the bank will negotiate a settlement if it loses this round rather than start a new battle about the passage of time.

Both James and Anne are close to people who still won’t talk about what happened in the doctor’s house. Shame alone can’t explain it. “People are still very, very loyal,” James says. “You’ll find that a lot. That’s how this guy got away.”

“A lot of people still think: But that was just the way things were,” Anne says. “I hate that. That was just accepted. And because it was the culture at the time doesn’t make it right.”

An apology would mean as much to her as a check. “I would just like Barclays to put their hands up and just say sorry,” she says. “I would just like a conclusion. I would just like it to end.” —With Kaye Wiggins

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Friedman at rfriedman5@bloomberg.net, Jeremy Keehn

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.