The Hunt for the Next Blockbuster Manga

The Hunt for the Next Blockbuster Manga

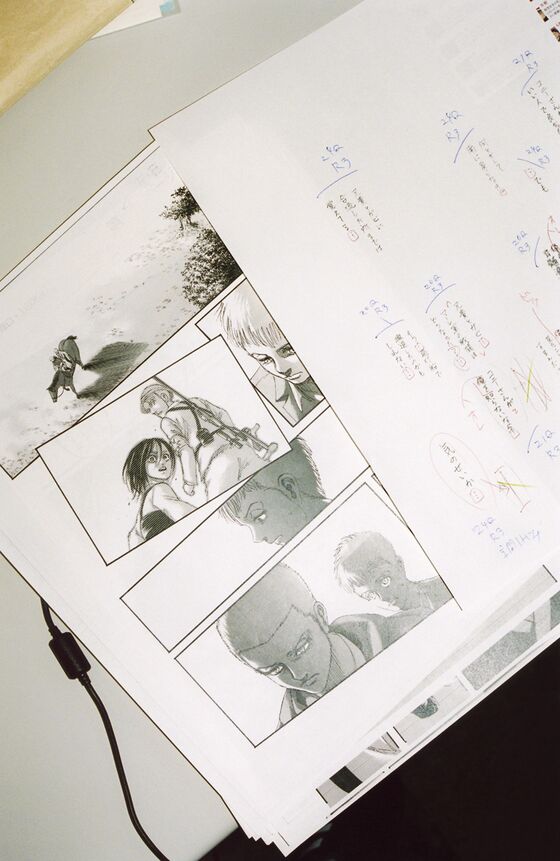

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- One day last July, Hajime Isayama spent a morning strolling through a chic modern art gallery on the 52nd floor of the Mori Tower, which looms over Tokyo’s upscale Roppongi neighborhood. The gallery walls, which have since been adorned with paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat, were lined with original artwork from the manuscript pages for a bestselling manga, or comic book, Isayama’s Shingeki no Kyojin (Attack on Titan).

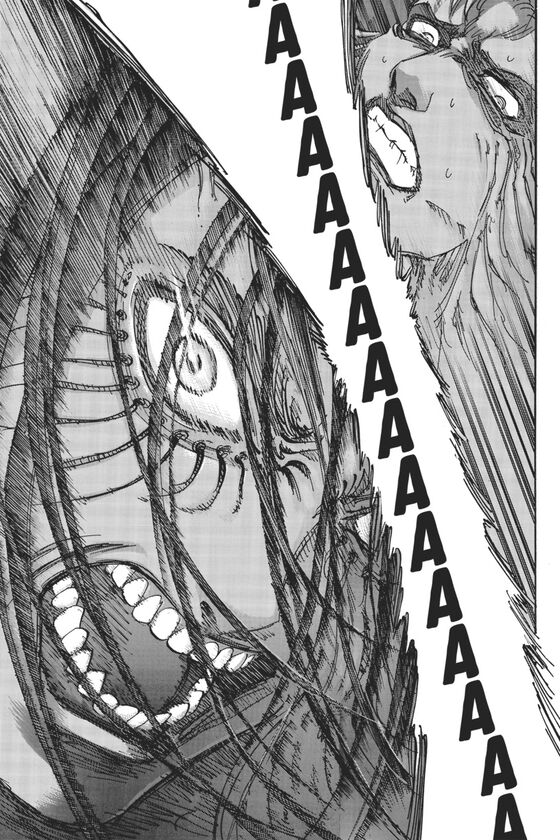

The exhibition commemorated the 10th anniversary of this gory epic, which is set in a world dominated by flayed, vascular, man-eating behemoths, tall as the Mori Tower itself, who terrorize walled-off cities where humanity has taken refuge. In the decade since Titan was first printed in Bessatsu Shonen Magazine, its antagonists have left their gigantic footprints all over Japan’s popular culture. The country’s largest publisher, Kodansha Ltd., has issued about 100 million copies of its 31 serialized volumes. The animated television adaptation is an international hit that has in turn generated a live-action film franchise, several video games, and merchandise including toys, tote bags, and limited-edition packaging for a popular Japanese laundry detergent.

At the exhibition, Isayama draped his wiry frame in a plain hooded sweatshirt, and he wore a medical mask to disguise himself from the fans who’ve made him by far the most successful manga artist of his generation. But the mask only accentuated his distinctive hair, which hangs down the sides of his face like angular black drapes. At 33, he’s achieved a level of fame at home that would be unfathomable for a comic book artist in America. Practically everyone in Japan reads comics, whether serialized in weekly or monthly manga magazines such as Shonen Jump or collected in volumes called tankobon. The artists, who typically both illustrate and write, are venerated as auteurs.

Isayama peered over the shoulders of the high school students, housewives, and salarymen attending the exhibition, drinking in their unfiltered chatter. The conversations weren’t unlike the fan discourse surrounding Game of Thrones, in their focus on plot twists, shocking deaths, and gruesome set pieces. The two works share a particular tendency to kill off their protagonists. Both have also, at their heights, been industries unto themselves.

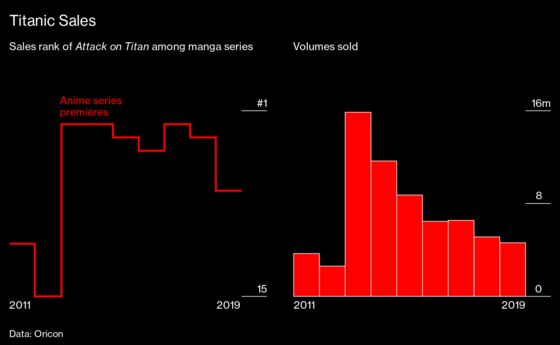

“Back when the series first got picked up, there were constant news reports that Kodansha was seriously in the red,” Isayama said. “I had no idea how long any of this was going to last.” Instead of becoming a casualty of Kodansha’s financial woes, though, Attack on Titan turned out to be the publisher’s answer. When an animated TV adaptation was introduced in 2013, sales of the comic soared, lifting Kodansha’s sales for the first time in 18 years and returning it to profitability.

A comic this successful might be expected to run for 100 volumes or more—one of Isayama’s favorites as a child was JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, which came out the year he was born and remains in print as its creator, Hirohiko Araki, periodically reinvents his protagonist. Isayama, though, has decided he’s run out of story to tell. His manga and anime TV series will complete their final story arc sometime in the coming year.

Kodansha will be left with a very large financial hole to fill. Attack on Titan has for years insulated the publisher against industry trends that it will have to confront head-on. Domestic revenue from sales of print manga volumes, which comprise almost half of Japan’s $12 billion-a-year book market, plunged to an all-time low in 2017 and fell a further 5% in 2018, according to Japan’s National Publishers Association. (Revenue jumped 5% in the first half of 2019, the most recent period for which figures are available, but only because of an industrywide price hike.) Sales of digital comics have been an exception, climbing steadily in recent years and getting a boost this spring, when many Japanese bookstores were closed to halt the spread of Covid-19. But rampant piracy and lower prices make digital manga less profitable than traditional paper comics.

The pressure on Kodansha is all the more intense because it coincides with a moment of great opportunity. Demand for adaptation-friendly storylines is higher than ever, the result of a fierce fight between Netflix Inc. and Hulu LLC to become global leaders in anime streaming. In 2017, Netflix shook up the industry by luring Taiki Sakurai away from Production I.G Inc., the studio responsible for one of the most successful animes of all-time, Ghost in the Shell. Sakurai’s first Netflix series was Devilman Crybaby, based on Kodansha’s surrealist manga Devilman, from 1972.

But Kodansha and its rivals must do more than simply mine their back catalogs if they’re to thrive. Japanese manga publishers receive only a modest share of licensing income, so for them anime serves primarily as comic book ads. Unlike Marvel and DC, which retain great control over the worlds their company artists and writers invent, Japanese comics publishers work in a system that defers to the creator.

“The author has almost absolute control in Japan,” says Jason DeMarco, who’s been licensing anime for Turner Broadcasting System Inc.-owned Cartoon Network Inc. for more than two decades. “That’s totally different from U.S. publishing, where it’s like, ‘Thanks for creating Spider-Man—now get the f--- out of here, so we can make a lot of money off of Spider-Man.’ ”

When I met Isayama at Kodansha’s Tokyo headquarters in January, the deference accorded to successful manga creators was evident: The artist, who works from an apartment near his home, was greeted with deep bows and bags filled with gifts. Erika Kato, a licensing manager in the international rights department, thanked him profusely for agreeing to be interviewed, which he rarely does these days. Isayama was dressed casually, in blue jeans and a hoodie, like a man who works from home. His sleepy countenance and frequent yawns suggested he was doing little else there.

On my way to the interview, I’d picked up a copy of Isayama’s most recent tankobon, whose cover advertised a forthcoming Attack on Titan ride at Universal Studios Japan. Kodansha had helped arrange a string of licensing and advertising partnerships to help end the series with a bang. Each of these—including the Mori Tower exhibition, which generated about $2.5 million in ticket sales—depended on Isayama’s approval. “These kinds of commercial opportunities aren’t going to last forever, so I don’t turn my back on them,” he said. “It’s nice to think that the world of Attack on Titan will continue on just a little bit longer.”

He was keenly aware that he was securing his artistic legacy, too. “I was a big fan of Game of Thrones, so I can relate to the feelings of those fans who were disappointed with how the series ended,” he said. “But when I’m drawing, I’m expressing my own feelings, and I think as long as I’m doing that, my fans will be able to accept whatever ending I come up with for them.” He’s already decided how the narrative will conclude, but knowing where he’s headed hasn’t saved him from agonizing at times over how to get there. Attack on Titan is a multifaceted epic, with dozens of characters wrapped up in intersecting plotlines. Competing mythologies and histories, and even alternate dimensions, complicate a text marked by political, strategic, and social intrigue and themes of betrayal, revenge, and resurrection.

Kodansha’s finances and identity depend on having at least one tentpole blockbuster series aimed at adults. Its two biggest rivals rely on slightly different models: Shogakukan Inc. supplements its original titles by licensing popular video game characters such as Nintendo Co.-owned Pikachu, of Pokémon fame, and Sega’s Sonic the Hedgehog, for children’s comics. Shueisha Inc. focuses on original youth-oriented hits, such as Dragon Ball, One Piece, and My Hero Academia.

Kodansha’s approach traces to the 1980 introduction of Young Magazine, a biweekly packed with about 300 pages of serialized comics. The books were aimed at young adult men, who were increasingly flush with disposable income as Japan entered an economic bubble. In 1982, Young began publishing Katsuhiro Otomo’s cyberpunk classic Akira, which chronicles a violent confrontation between psychics, biker gangs, and the military in a post-apocalyptic “neo-Tokyo” of 2019. The magazine’s circulation soon surged to more than a million readers, prompting Kodansha to start issuing standalone Akira tankobon. When the series wrapped up in 1990, its six volumes collectively formed a graphic novel of more than 2,000 pages; millions of copies have sold worldwide. The film adaptation brought in $49 million in global box office receipts and an additional $30 million in VHS sales after its 1988 theatrical release and became one of the most influential science fiction films of all time.

One of the people influenced by Akira was Masamune Shiro, who would prove to be Kodansha’s next wunderkind. His seminal manga, Ghost in the Shell, was serialized in Young Magazine from early 1989 to late 1990, and it, too, got its own tankobon, anime film, and English-language edition. Groundbreaking, commercially successful comics come along only so often, though, and Kodansha hit a dry spell just as Japan’s bubble years came to an end. By 2002 the company’s sales had fallen low enough to drag it into the red for the first time since World War II.

The Isayama era began before the decade was out, but here Kodansha was lucky: Attack on Titan came to the publisher only after Shueisha passed. In 2006, Isayama called Kodansha to request a meeting, reaching an editor named Shintaro Kawakubo. He saw enough potential in Isayama that he gave the fledgling artist homework assignments to improve his illustration skills. “I asked him to practice redrawing action sequences from Hajime no Ippo,” Kawakubo says, referring to a popular boxing manga. “And since he wasn’t good at drawing clean lines, I had him redraw scenes from romance manga.”

As a storyteller, though, Isayama was a natural. The comic seemed, at a glance, to be a niche story, with a unique setting that would appeal to “comic book geeks,” Kawakubo says. But “looking deeper, it had all the makings of a mainstream hit.” More than most artists, Isayama seemed able—and willing—to view his characters from a marketing perspective as well as an artistic one. He knew how to leave readers wanting more—how to keep them coming back issue after issue with plot twists and cliffhangers, almost as though he was writing for TV.

Kawakubo traces this sensibility to Isayama’s move to Tokyo from rural Oita prefecture. “He thought deeply about what readers wanted from him, because failing to deliver would mean returning to work a day job until his next series came along,” Kawakubo says. “Because of that mindset, he’s become an author who is capable of thinking like a manga editor or an anime producer.”

In 1996, DeMarco and Sean Akins, two creative directors at the Cartoon Network, were charged with filling a new block of after-school programming. They came up with Toonami, a four-hour show that reflected their off-kilter tastes. It mixed Hanna-Barbera cartoons such as Birdman with older anime like Voltron and Robotech, which could be licensed for virtually nothing—more or less the budget DeMarco and Akins set out with. After Toonami did well in its first months, their boss tossed them some pocket money for more anime.

“Dragon Ball Z was one we knew about, because we had watched bootleg VHS tapes that we rented from a Japanese home video store here in Atlanta,” DeMarco said when we met at the Georgia offices of Adult Swim, Cartoon Network’s late-night programming block. When they added it to their lineup in 1998, major distributors such as Bandai Co. and Funimation Productions LLC started coming to him with pitches for other shows. Eventually Toonami moved to Adult Swim, where it introduced American viewers to iconic manga characters such as Sailor Moon before dwindling ratings led to its cancellation in 2008.

DeMarco is now vice president and creative director of Adult Swim. Sitting in a conference room named for Astro Boy, wearing jeans and a black T-shirt with a faded image from a horror manga by Junji Ito, he looked like a linebacker who’d gone on vacation in Japan and never come home. He told me about the Cartoon Network’s decision to bring back Toonami in 2012. The revival began as a one-time April Fool’s Day nostalgia trip for die-hard fans, but when it got tremendous ratings and social media attention, DeMarco decided to make it permanent.

To fill the block he turned to his contacts at Funimation, who showed him a teaser trailer for the Attack on Titan anime it was seeking to distribute. “It was literally just an image of the titan coming over the wall,” DeMarco told me. “When we saw that we were, like, ‘Hell yeah!’ We didn’t even read the comic, we just said, ‘Yeah, we’re interested in this.’ I’m a big horror fan, and the idea of a skinless, giant humanoid eating people—you don’t have to work hard to sell me on that.”

Toonami began including Attack on Titan in May 2014, seven months after the first season concluded in Japan. It was an immediate hit, bringing in about 1.3 million viewers in its midnight time slot. “You’re talking about a crazy Japanese show that’s drawing as big an audience as Family Guy, which is one of the biggest hit cartoons in the U.S. in the last 20 years,” DeMarco said. “That’s about as mainstream as anime can get in the U.S.”

The show’s success helped tilt the U.S.’s entire comic book market to the East. From 2015 to 2018, Barnes & Noble Inc. doubled the shelf space it devoted to manga and began holding “Manga Mondays” sales events. That helped Attack on Titan, which had fewer than a million English-language copies in print at the end of 2014, approximately triple its print run within a year. Some 4 million copies have now been issued, plus almost 1 million downloads of the digital edition. The windfall caught everyone involved with the show off guard. They hadn’t planned for another season, leaving fans to wait until 2017 for another.

Around the time the anime returned, Netflix Japan dropped what DeMarco calls a “money bomb” on the market. Netflix hasn’t said exactly how much cash it invested, but its chief content officer, Ted Sarandos, told analysts late that year that it planned to spend a significant chunk of its $8 billion original-content budget on anime. Greg Peters, Netflix’s chief product officer, attributes the company’s interest in part to how well anime works with streaming technology: “If you take something like anime, which is superefficient from an encoding perspective, we can now provide an amazing quality video experience for anime titles on mobile.” This mobile-friendliness dovetails neatly with the genre’s target market.

Netflix’s hunt has taken a two-pronged approach. One is the old-fashioned route of forging partnerships with production companies and acquiring licenses, including one for a reboot of Kodansha’s Ghost in the Shell. The other is producing its own anime in-house; Netflix’s first original anime series, Eden, is scheduled to premiere before the end of the year.

The second path is tremendously risky for producers, however. Original anime films of the kind done by Hayao Miyazaki (Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away) can take years and tens of millions of dollars to produce, and they come without the built-in audience of a successful manga. Nao Azuma, a spokeswoman for Netflix Japan, says finding talent also has been a challenge. “It’s a very new type of platform and so it takes convincing,” she says. “We’re hoping that the content we’re producing is inspirational for creators and gives them some sense of what’s possible here.”

For now, the incentives favor licensing. Walt Disney Co.-owned Hulu is also in the game, armed with an exclusive first-look partnership with Funimation that gives it access to all the most important players in anime. The result has been to push up the price for everyone hoping to acquire manga properties.

DeMarco says all this activity is a good thing for creators—and by extension publishers—even if it’s made his job harder. He’s been trying to innovate; for one recent deal, he skipped the middleman and went directly to Shogakukan to acquire the rights to Uzumaki, a manga by Junji Ito about a town cursed by spiral shapes (found on boys who’ve transformed into snails and women whose hair has come alive). Adult Swim agreed to fund the project from scratch. DeMarco describes it as more of a labor of love than a paradigm shift. Producing original anime takes so much time, he says, “that we’d have to shut down for three years in order to have enough shows ready to fill a whole Toonami block.” It was worth it to DeMarco this time, though, if only for the chance to work with a manga artist he reveres.

Manga publishers, for their part, are mindful that there are limits to how much they can rely on anime. Two editors I spoke with at a Kodansha rival, who requested anonymity discussing confidential business arrangements, pointed out that these deals aren’t necessarily a dependable source of revenue. “In the end, the pie gets sliced up so many ways that a publisher might get nothing out of it aside from a boost in comic book sales,” one said.

If anime is driving Kodansha as it hunts for the next Attack on Titan, Kawakubo, who’s charged with leading the search, isn’t letting on. The process he describes for recruiting new talent remains basically unchanged after decades: Editors seek out published artists whose work they like, as well as newcomers scouted at Japan’s manga trade schools or in contests the company holds, and try to foster great work.

A hit comic, Kawakubo says, can’t be engineered—“the magic is either there or it isn’t.” It starts the way Titan did, with telling a good story. “If you make a manga that’s not worth reading, no one will want to make it into an anime series,” he says. “And if you’re focused from the start on what might make a good anime, or what the next trend might be, you’ll never make anything worthwhile.”

in the spring of 2018, I met with Shinzo Keigo at a coffeehouse in the west Tokyo suburbs, not far from Studio Ghibli, the shop where Miyazaki has been producing masterpieces since 1985. Like Isayama, Keigo is 33, but his path to becoming a professional manga artist was more typical. Starting in 2008 he published seven comics with Shogakukan, including a few indie hits that were made into films or TV programs. It was creatively fulfilling, but yeoman’s work for a modest wage.

I’d first spoken with Keigo a few weeks before, as he was promoting a live-action TV show based on his most recent work for Shogakukan, Tokyo Alien Brothers, which chronicles the adventures of two slacker extraterrestrials sent to investigate life on Earth. It was envisioned, he told me over coffee, as a kind of “reverse version of the Christopher Nolan film Interstellar,” and it sold well enough across three standalone volumes to catch the attention of producers at Nippon Television Network Corp., which aired a live-action adaptation of the manga in the summer of 2018.

Keigo was doing well enough at Shogakukan that he might have carved out a long career there, producing respected, adaptable hits that complemented to the company’s robust Pikachu business. But shortly after we met, he announced that Kodansha would publish his next series, Nora and the Weeds, about a police detective and a mysterious girl who reminds him of his dead daughter. “Working with Shogakukan was nice,” Keigo told me the next time I saw him. “But Kodansha is the kind of place you dream of being as a manga artist.”

After landing at one of the company’s second-tier magazines, he’s gone on to do well, publishing a few Nora and the Weeds tankobon and selling the translation rights to a publisher in France, where he has a following. Still, he didn’t have any illusions of becoming the next Isayama.

Then again, Isayama never imagined such a thing when he began drawing Attack on Titan while working a part-time job at an internet cafe. And although he’s giving up his series now, he isn’t necessarily giving up his stature. The next Hajime Isayama could well be Hajime Isayama. “I’ve actually floated about five different ideas for new serialized manga, but so far they’ve come to nothing,” he said. “I think I’d like to try doing a more realistic manga, but I haven’t yet been able to produce a manuscript that’s up to my own standards.”

Read more: The Next Streaming Showdown Is a Race for Eyeballs in Southeast Asia

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.