Intelsat Pitch to Sell U.S. Airwaves Sparks Fight Over Spoils

With $60 Billion of Airwaves for Sale, a Fight Over Who Gets the Money

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Television shows reach viewers in the U.S. via a network of satellites that relay everything from NBC’s Today show to Fox’s Thursday Night Football. Local stations and cable outlets in turn send those shows to more than 120 million American households. Now the two giants of the TV-beaming business—Intelsat SA and SES SA, both based in Luxembourg—along with Ottawa-based Telesat want to sell access rights to some of the frequencies they use. These frequencies are part of a swath known as the C-band, and they’re good for more than just transmitting sitcoms and soaps. Whoever gets access to them will be in the pole position in the race to capture the 5G market.

Different frequency ranges (otherwise known as bandwidths or spectrum) have different characteristics: Higher frequencies can carry more information but don’t travel very far, whereas low frequencies travel farther but don’t carry much data. The C-band airwaves are in a Goldilocks range: just right to carry the amounts of data required for 5G over a long enough distance that building out a network wouldn’t be prohibitively expensive.

While the U.S. owns the airwaves, it licenses them to private companies in a process overseen by the Federal Communications Commission. President Trump has promised that the U.S. will continue to dominate the global tech industry in the 5G era, yet few of these Goldilocks airwaves have changed hands since he took office. Intelsat says it and SES control more than 90% of the C-band in the U.S., and the prospect of all that 5G bandwidth becoming available has drawn interest from mobile carriers Verizon and AT&T, cable provider Charter, and even tech giants Microsoft and Google.

But there’s a catch. The airwaves could fetch as much as $60 billion at auction, and some on Capitol Hill want to keep that money. This would require the FCC to take control of the sale: By law, proceeds of an airwaves auction by the commission go to the U.S. Department of the Treasury. “The American taxpayer deserves to be compensated for this,” says Representative Mike Doyle, a Pennsylvania Democrat, who’s introduced a bill to ensure public control of the sale. “It just seems crazy to me that there’s a chance to put $40 to $60 billion in the Treasury—and we’re not going to do that?”

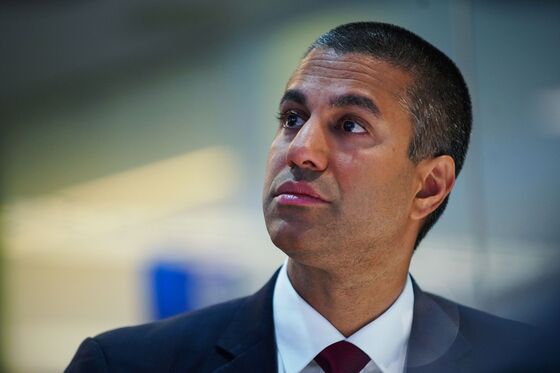

The decision to approve the sale and how to run it rests with the FCC, and Chairman Ajit Pai has pledged to announce a decision soon. The three satellite companies—known as the C-Band Alliance—have argued that a private sale will be faster than one run by the FCC. “We have acted in the best interest of the U.S. by developing and proposing a technically sound proposal,” said Dianne VanBeber, an Intelsat vice president and C-Band Alliance spokeswoman, in an emailed statement. “Clearing spectrum quickly, enabling 5G in the U.S., generates tremendous public policy and economic value.”

Pai has been evasive on how long a public auction would take, but at an Oct. 17 Senate hearing, he didn’t contest an estimate of three years. The alliance says it could handle the task in as little as 18 months. “The faster the spectrum gets deployed, the better the chance the U.S. wins the 5G race,” says Paul Gallant, a Washington-based analyst with investment bank Cowen & Co. “Speed to market is critical. This is beachfront property.” Broadcasters warn that the bandwidth remaining after the airwaves sale may not be sufficient to handle today’s video traffic, but the alliance says it will ensure service continues.

For Intelsat especially, the stakes are high. With roots in the satellite business dating to the 1960s, it’s now struggling under $14 billion of debt. Without the sale, the company’s value could plunge by more than 90%, according to an estimate from New Street Research. “The satellite companies almost certainly would keep less” through an FCC auction, says Gallant. If allowed to run the sale itself, the alliance has pledged to make a “voluntary contribution” to the Treasury, though it hasn’t said what the payment would be.

Whether Congress can force the FCC to reduce the companies’ payout isn’t clear. Lawmakers don’t directly control the agency, and it takes time to pass a law. “The FCC likely has broad leeway in deciding how to slice the pie,” said Matthew Schettenhelm, a Bloomberg Intelligence analyst, in an Oct. 25 note.

Groups that track federal spending have sought to influence the process anyway. At the Senate hearing, David Williams, president of the Taxpayers Protection Alliance, warned against letting the satellite companies pocket the sale’s proceeds. “I’ve been doing this for 26 years, and people say, ‘What’s the biggest taxpayer rip-off you’ve seen?’ ” he said. “This is top 10.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.