Zimbabwe’s Currency Plans Upended as It Fights on Two Fronts

Zimbabwe’s Currency Plans Upended as It Fights on Two Fronts

(Bloomberg) -- The fallout from the coronavirus pandemic has upended Zimbabwe’s plans to enforce the use of its own currency and left it scrambling to find money to tackle twin crises of economic collapse and famine.

A global slump spurred by the outbreak of the virus has come with the southern African nation’s economy in its worst state since at least 2008. Already trying to raise $400 million to buy grain after the most-severe drought in 40 years threatened to leave half of its people without enough food, it now needs another $220 million to deal with the impact of Covid-19, according to Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube.

“We are working with the two crises, we are fighting on both fronts,” he said in an April 16 interview. “Our issue is just financial resources.”

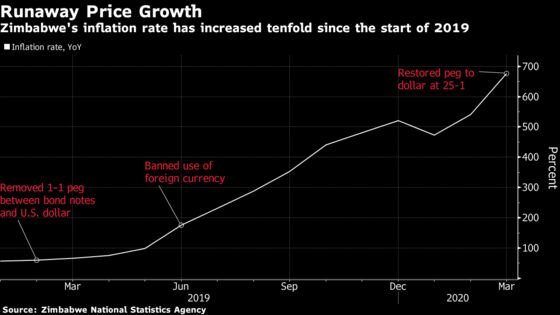

Zimbabwe’s economy has been in free-fall as a shortage of foreign currency led to scarcity of fuel and wheat. Conditions worsened after the government removed a 1-1 peg between a quasi-currency known as bond notes and the dollar more than a year ago and in June banned the use of foreign exchange as it sought to reintroduce the Zimbabwe dollar that had been scrapped in 2009.

The situation has been compounded by the imposition of a national lockdown, which has now been extended to May 3, to curb the spread of the disease. The International Monetary Fund estimates the economy contracted 8.3% last year.

Now, to contain the fallout the local currency has been pegged at 25 to the dollar, still well below the black-market rate, and the ban on the use of foreign currency has been lifted.

Derailed plans

“You are allowed to keep your U.S. dollars under your pillow” and they can be used in shops, Ncube said. “Our plans are derailed. We are determined to get back on track once the Covid-19 outbreak” is over, he said.

The decision may improve trading as retailers were reluctant to accept local currency that couldn’t be used to import goods.

“It means we can easily buy from our suppliers,” said Mikey Goredema, 28, who sells building materials in an outdoor market in Harare, the capital. “The U.S. dollar was what people wanted, even when it was illegal.”

It’s a setback for Ncube, an economist who has lectured at the University of Oxford and who tried to instill financial discipline since accepting the post in September 2018. He has slashed government spending, set up a monetary policy committee and introduced a benchmark interest rate.

Despite those measures, the country failed to attract significant foreign investment, has external debt of $8 billion that it can’t repay and annual inflation surged to 676% in March. Ncube admits a target of double-digit price growth by the end of the year may be difficult to attain.

“It has all been complicated by Covid-19,” he said. “It’s very hard to get our targets.”

The country isn’t eligible for funding from the IMF, due to arrears to other multilateral lenders, but has received some assistance from the European Union and the U.K. as well as from a number of organizations, Ncube said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.