Xbox: The Oral History of an American Video Game Empire

Here is the story of how an ungainly, over-budget project spawned a gaming powerhouse.

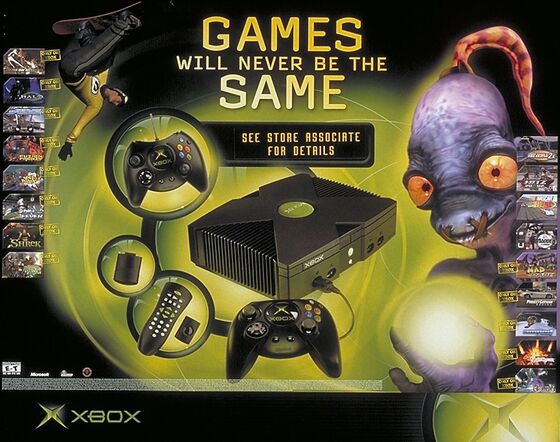

(Bloomberg) -- The box looked like an old VCR, the controller was comically large, and it was made by one of the most boring companies on earth. Somehow, the Xbox triumphed and gave Microsoft Corp. the first—and last—successful video game console brand from an American company since Atari.

Twenty years later, Bloomberg asked two dozen people instrumental in creating the Xbox to recount how they did it. Microsoft broke into an industry dominated by Japanese companies and reshaped the business around shooting games and online play. Efforts by Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc., Facebook Inc. and Google to crack the industry in the years since have come nowhere close. Video games now account for more than $11 billion a year for Microsoft and have established the Xbox as a premier brand.

Video games didn’t come naturally at Microsoft. The company had been singularly driven by the sale of Windows and Office software. It emerged in 2001 badly bruised from an antitrust battle on two continents and with a crippling anxiety about what to do next. Microsoft was increasingly paranoid about the rise of Sony Corp., which had the PlayStation, and became fixated on carving out a place for itself in the living room.

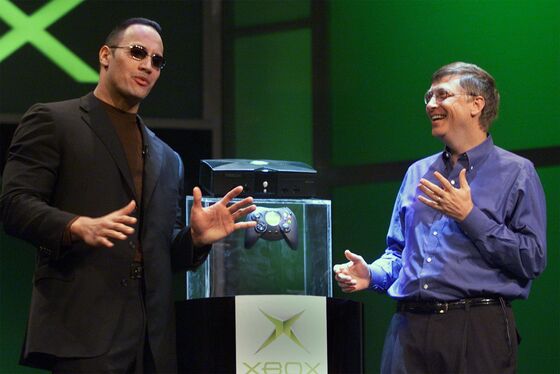

Some Microsoft employees were spending idle time around the office toying with the idea of building a console. The project got its spark, as things often do inside big companies, at an executive retreat. The next two years brought competing visions, infighting, numerous focus groups and near-cancellation of the product, until a team of 2,000 delivered something Bill Gates could unveil onstage, standing beside a famous pro wrestler, to a bemused audience in Las Vegas.

“We needed to penetrate the living room,” said Steve Ballmer, then the chief executive officer of Microsoft. His former boss, the co-founder Bill Gates, said: “Xbox might seem like an unlikely success story to other people, but it wasn’t a stretch for me to believe in this project and the people who were bringing it to life.”

“I was very cognizant of Microsoft’s market power. Look, they may have all been the world’s nicest guys,” said John Riccitiello, then the president and chief operating officer at video game publisher Electronic Arts Inc. “But they’re also the guys that shut down Netscape.”

In the original team’s own words, here is the story of how an ungainly, over-budget project spawned a gaming powerhouse.

A Game Console Is Born

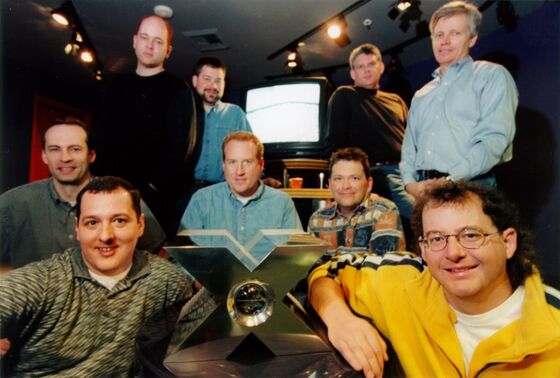

Jonathan “Seamus” Blackley was a cog at Microsoft working on programming tools for PC game developers. On the way back from a personal trip in 1999, he had an idea.

SEAMUS BLACKLEY (technology officer for Xbox) I visited my girlfriend who had moved back to Boston. On the flight back, I started thinking, Now, PlayStation had just announced PlayStation 2. They had advertised it was going to have Linux on it, and it was going to be a competitor to the PC. I think there was a little bit of mistranslation, or they didn’t understand that it might be a bad idea to taunt Microsoft this way.

KEVIN BACHUS (director of third-party relations) Sony coming out and saying, “PlayStation 2 is going to redefine the computer world,” that got attention inside of Microsoft.

BLACKLEY Everybody who made PlayStation games worked on a PC to make the game. And the attack that I realized we could make would be to just make the PC into the console.

Around the same time, 47 of Microsoft’s top executives, including co-founder Bill Gates, convened at a resort near the Canadian border for an annual retreat.

RICK THOMPSON (first head of Xbox) One of the exercises that you do is each of the attendees writes a question down on a big piece of paper. Each person holds their question in front of them, and you read different people’s questions. Then the moderator invites you to drop your idea if you don’t think it’s very interesting and to go stand behind the person with the most interesting idea. By the time the process was done, I had 15 people standing behind me, including Bill Gates. I asked something like, “What if the biggest cable company, internet provider and game console all got together?”

ROBBIE BACH (second head of Xbox) Bill had proposed some topic about architecture that he wanted to work on. Nobody wanted to meet with Bill on his architecture topic. So Bill decided to come to our group. We talk for an hour and a half about whether Microsoft should do a video game console. Bill decides that it’s worth exploring.

THOMPSON Sony had decided to start showing a vision of the future, which was a home without a PC in it. What Sony was showing was three or four PlayStations in every home and no computers. You can’t say that to Steve Ballmer. The man is driven by playing defense. And the Windows guys were like, “This is not OK.”

STEVE BALLMER (president and soon-to-be CEO of Microsoft) The whole theory of a computer on every desk, in every home, Windows everywhere, I totally bought into that.

THOMPSON By May, we had competing teams looking at competing approaches. We were doing crazy demos for Bill. It was different groups basically trying to slit each other’s throats.

One team was from the game developer tools group called DirectX, led by Blackley and Bachus. The other involved some employees who worked on the failed Panasonic Corp. game console, the 3DO, who joined Microsoft through the acquisition of WebTV, an early set-top box that would also fail.

JENNIFER BOOTH (head of Xbox market research and planning) I ran an engineering group, as well as product planning, and my counterpart in marketing happened to be Don Coyner, who came from Nintendo. One day, Don and I got a call from Seamus Blackley and Kevin Bachus, and they said, “Can we have lunch with you? We’re thinking of starting a console.” We’re like, “What! There’s no way Microsoft will!” We started to moonlight and help them.

BACHUS The original idea for Xbox, which we called the Windows Entertainment Platform at the time, or the code name was Midway, was really one of a PC appliance.

ED FRIES (head of first-party games) I got approached by these guys from the DirectX team. They had this idea that was the DirectX Box, or Xbox for short. What interested me about it was that as originally imagined, it was literally going to be a PC that was pretending to be a game console.

BACHUS That was what we pitched everybody. That’s what we pitched Bill.

FRIES It turned out there was another group of people pitching a console idea. It escalated pretty quickly, and in typical Microsoft fashion, we rounded up all our vice presidents, and they rounded up all their vice presidents. We had a Bill and Steve-level meeting to decide. They went first and presented their project. I would describe it as very much like a traditional console. It was custom hardware, custom software, custom systems software, custom everything. And our thing was, at that time, it was a PC. So our argument was to paint them as being off-strategy in Microsoft terms. So obviously, we won.

THOMPSON By June, it might’ve been July, there’s a big meeting, a dozen VPs, 50 people in the room. And the DirectX guys are saying, “We want to go off and start working on this thing.” One of them was this guy, Nat Brown. Brown was not in the room. He’s on a squawk box, and the last thing he says on this several-hour phone call after they pretty much get the go-ahead is, “We want Rick Thompson to lead it.” I turned bright red and said, “I'm not big enough for this job.” The next day, Ballmer showed up in my office with a baseball bat in his hand, literally, and told me that this is what I was going to do.

BALLMER I don’t remember that, but it’s possible. I’m sure I was playing with the baseball bat. People used to think I meant it as a threat, but some Microsoft customer had given it to me, and I’m a hyperactive dude, so it was something I was always sort of nicking around with. In defense of my reputation, I have ADHD, but I am not mean.

THOMPSON J Allard showed up and sat down in my office. He was on crutches, and Cam Ferroni is with him, and he was like, “I’m your software department.” And I’m like, “Who are you?” He goes, “Have you ever heard of Internet Explorer? That was me.”

J ALLARD (general manager) Sounds like something we might have said.

It didn’t take long for the team to discover that the initial plan, to design a gaming PC and get other companies to build it, wouldn’t work.

BACHUS Michael Dell said, “The problem with the game console business is that when Sony announces they’re reducing the price of PlayStation, their stock goes up. When I say that I’m reducing the price of the PC, my stock price goes down.”

BACH Even more impactful, actually, was Electronic Arts basically told us, “If you try to do that, we will not support it,” because they knew that if somebody wasn’t fundamentally behind the economics of the hardware business, no volume would ever be driven.

BACHUS We realized very quickly that things were going to have to change. J Allard, they brought him in to be adult supervision for me and Seamus because, well, he was right about the internet, so maybe he’ll be right about this, too.

BLACKLEY There were some guys who worked on Xbox early on who called it Coffin Box because they worried that it would fail and end their career at Microsoft.

BACHUS We started locking it down. It was going to be, not exactly what the WebTV guys had proposed but certainly more in that direction. Microsoft would build its own hardware, and the software would be developed specifically for the Xbox.

THOMPSON J and I had to go into Bill, and we told him it wasn’t going to be Windows.

ALLARD Bill can be quite animated.

THOMPSON We literally, like, needed towels to wipe the spit off our faces because Bill is screaming and yelling at us. But Bill being Bill, he’s very, very angry that he’d been misled, which he deserved to be. But within a half hour, he was like, “Yeah, I understand. Get out of my office, you two jerks.”

BALLMER We made this very conscious break, which was one of the hardest things, to not use real Windows. Did I say, “Gamers are a must-have market?” I probably can’t say that. No, I said, “We must be in the living room, and if the path to being in the living room is gaming, let’s take it.”

BACH On December 21st of ’99, we had a meeting with Bill and Steve, where Rick presented the revised proposal, which was for Microsoft to do the hardware itself. In theory, they knew our technical plan.

ALLARD I met with Bill no fewer than six times to discuss the technical plan in detail.

BACH In hindsight, it was not clear they fully processed it.

The Valentine’s Day Massacre

Nine senior employees gathered in the executive boardroom at 4 p.m. on Feb. 14. Most had dinner plans with their partners that evening. They expected a routine meeting, but it quickly became evident their bosses were not convinced of the plan to invest large sums of money in a console without Windows software. Making matters worse, the team had forgotten to carry out one crucial pre-meeting ritual.

FRIES Robbie would play basketball with Steve. Basically, what Robbie would do is something that we ended up calling “pre-disastering.” That’s where Robbie would let slip on the court that there’s some kind of bad news coming up, and then he’d work it all out ahead of time. For whatever reason, the pre-disastering didn’t happen.

BACH Bill is about 15 or 20 minutes late, and he’s pissed. And he comes in shouting and slams his fist on the table and says a bunch of things I won’t repeat. The gist of it was: You’re screwing Windows.

FRIES Bill throws the PowerPoint deck down on the table and says, “This is a fucking insult to everything I’ve accomplished at this company.”

BACH I’d been there, at that point, 12 or 13 years and been told I was a knucklehead at least five or six times. It was just kind of the way the company communicated.

FRIES We all turned to J, because J was in charge of the system’s software, and J was normally great with Bill and also was never afraid to stand up for himself.

ALLARD I was only 30 and had a lot to learn (and still do), but I had 10 years in the company, shipped dozens of products.

FRIES When we turned to look at J, he just kind of had that deer-in-the-headlights look, and nothing was coming out of his mouth. I stepped in and tried to explain, and Bill yelled at me and shut me down. And then Robbie started to talk, and Bill yelled at him. By then, J had snapped out of it and started to defend the decision. Ballmer, meanwhile, had been flipping through the slides and started to see the big red numbers on the business side, so he gave Bill a break in yelling and started taking over yelling about how much money it was going to lose.

BALLMER I’ve been CEO for a month. So I’m in a new mode. It’s like, OK, this is my decision to make, not Bill’s.

ALLARD Internally, this was, and is, the most ambitious “from zero” effort ever.

FRIES Around 7 or so, we’re all thinking, Not only are we being yelled at for hours, but we’re missing our dinner reservations with our significant others. So we’re now in trouble at home and at work.

BALLMER I came into that meeting sort of as my first big CEO decision. It also was an emotional time. My dad was sick with cancer. He died a week after that meeting. It was a stressful time. I’m in this new job. I want to do it well, and this is my first big call.

BACH We’re not getting anywhere. So at some point during the meeting, I said to Steve Ballmer, “We’re not going to convince each other. So let’s just decide not to do this. If you guys are that concerned about it, let’s just stop.” And of course, that led to like another hour of angst about, “Well, Sony has got PlayStation 2 in the living room. They’re calling it a computer. What are we going to do about that?”

FRIES One of the vice presidents who had been quiet the whole time asks this question, “What about Sony?” So that basically stopped the room, and the way I remember it is, it got quiet for a second, and then Bill got that kind of funny look he gets when he’s thinking and said, “What about Sony?” And he turns to Ballmer, and Ballmer said, “What about Sony?”

BALLMER I think I knew at the beginning of the meeting that I wanted to say yes. I also knew that, man, this thing was going to get the Roto-Rooter of all Roto-Rooters before I would say yes.

FRIES Bill turns and says, “I think we should do it.” And then Ballmer says, “I think we should do this.” And then they said, “We’re going to approve this plan just like you guys asked for. We’re going to give you guys everything you want. You wanted $500 million in marketing money. You want to go off into a different set of buildings so people will leave you alone.” That part went super quickly, like five minutes quickly.

BACH So Steve looks up, and he says, “OK, we’re done. Bill and I will support this to the end.”

FRIES I walked out of there with Robbie, and I said, in what at that point was 15 years at the company, “That is the weirdest meeting I’ve ever been in.” And then a month later, Bill was onstage at the Game Developers Conference announcing the Xbox.

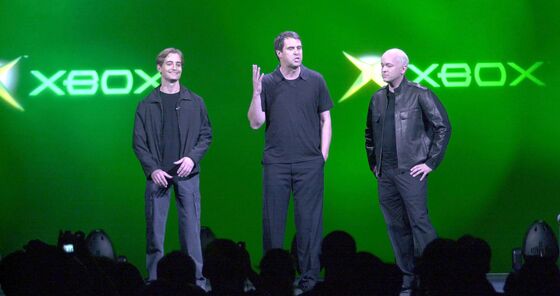

‘Who the Hell Are You?’

With Microsoft’s intentions known to the world, the team needed to secure some games to play on the new system. The rapid decline of the Japanese console maker Sega afforded an opportunity to lure game makers to the Xbox, and the biggest target was Electronic Arts, the publisher of Madden and FIFA. PlayStation launch veteran Booth, one of the few women in key roles on the team, offered critical advice on winning over developers.

BACHUS EA had just passed on supporting Sega, which was a real big nail in the coffin for Dreamcast. A number of people on the team, not myself, took to referring to the game publishers as Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. There was EA, and there was everybody else.

THOMPSON So I go in and meet with the CEO of EA (Larry Probst). First off, he’s like, “Who the hell are you? I’ve talked to Microsoft people forever, and I’ve never met you before.” And then I said, “Console,” and he said, “You guys don’t even know what it is to make a console. You have no clue.” I came back from that meeting going, Ah, that didn’t go so good.

JOHN RICCITIELLO (president and chief operating officer of Electronic Arts) What I said to Rick was, “This is cute, and it’s fun that you want to enter the market. And I wouldn’t discourage you, but you don’t have enough information here for us to really react to.”

BACHUS We met with EA a half-dozen times. They reminded us, Microsoft had a history of putting its toe in the water, and when things didn’t work out, they would abandon that market and pretend like it never happened. That’s all fine and good for Microsoft because it would be a rounding error on our balance sheet, but for a company like Electronic Arts, now there’s no platform, and their software is no good. Larry kept saying, “I want to know who gets fired if it fails.”

RICCITIELLO It was probably the impression we gave because we wanted to make sure we remained skeptical.

TODD HOWARD (producer and designer at Bethesda and project leader for Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind) I first heard about Xbox at GDC 2000. At that moment, it was hard to tell how serious they were. We said, “We’ll wait and see.”

BACHUS What we were advised by Jennifer Booth, who had worked for Sony during the launch of PlayStation, was: Bifurcate your message. Talk first about the technology, get the developers on board; then come back and talk about all the business stuff.

HOWARD Once we saw the full machine, spec-wise, we moved pretty quickly. The hard drive and the memory made such a difference in what you could do. It was a major step up from the PlayStation 2.

TOMONOBU ITAGAKI (creator of Tecmo’s Dead or Alive game franchise) Microsoft introduced an architecture that is very similar to PCs and made that style as de-facto standard in the industry. That is a huge contribution because it made game development much easier.

BACHUS We met with Tecmo, and I think they expected us to say, “We want Dead or Alive,” because that was a really important franchise. Instead, I had read that they were thinking about bringing back Ninja Gaiden. They expected these American guys throwing their weight around, and they were so taken by surprise that we ended up getting both franchises. Seamus and Itagaki built a strong rapport over the technology.

ITAGAKI I was waiting at a reception room. Then Seamus walked in, all by himself, plunked himself down on a couch. Then he was like, “We are making a game console. Are you joining or not?” He’s big and was like a marine soldier. Then we talked about a lot of things—horsepower of the machine, other technical specifications, launch date, planned installed base at the launch. All verbal, no papers at all. We talked for an hour or so, and my mind was set. My team’s mission was to create the world’s best fighting game, and we needed the Xbox for that. Xbox was four times to six times more powerful than the PS2.

THOMPSON Some of my meetings were absolutely hysterical. I flew to Japan to meet with a Konami executive. Everybody warned me this guy is a massive drinker. We had a translator because he didn’t speak a word of English, and in the span of a night, we drank an entire case of Asahi tall beers and a bottle of Courvoisier shots. At 4 o’clock in the morning, I make it back to my hotel. I show up at our 9 o’clock meeting. The executive shows up. Nobody else does. The translator was never seen again. The Konami guy just reaches his hand out across the table, shakes my hand and leaves, like, “Deal. I’m in.”

The team also looked to tap Microsoft’s deep financial resources to secure exclusive games. It approached various companies to propose an acquisition.

BOB MCBREEN (head of business development) The first company we reached out to buy was EA. They said, “No, thanks,” and then Nintendo.

BACHUS Steve made us go meet with Nintendo to see if they would consider being acquired. They just laughed their asses off. Like, imagine an hour of somebody just laughing at you. That was kind of how that meeting went.

MCBREEN We actually had Nintendo in our building in January 2000 to work through the details of a joint venture where we gave them all the technical specs of the Xbox. The pitch was their hardware stunk, and compared to Sony PlayStation, it did. So the idea was, “Listen, you’re much better at the game portions of it with Mario and all that stuff. Why don’t you let us take care of the hardware?” But it didn’t work out.

BALLMER I remember loving their content.

HOWARD LINCOLN (chairman of Nintendo of America) Nintendo does not talk about confidential discussions with other companies. In any event, nothing came of these discussions.

They also tried Square, the publisher of the Final Fantasy series and now known as Square Enix, and Midway Games, maker of Mortal Kombat.

MCBREEN We had a letter of intent to buy Square. In early November 1999, we went to Japan. We had one of those big dinners with their CEO and Steve Ballmer. The next day, we’re sitting in their boardroom, and they said, “Our banker would like to make a statement.” And basically, the banker said, “Square cannot go through with this deal because the price is too low.” We packed up, we went home, and that was the end of Square.

BACHUS We were talking to Midway about acquiring them. They were very serious about wanting to be acquired, but we couldn’t figure out how to make it work because we’d immediately get them out of the PlayStation business, and we didn’t need their sales and marketing group, and so that left us with not a lot of value.

The Best Acquisition Microsoft Ever Made

An unexpected opportunity arose with a little-known computer game developer, Bungie, which was working on a shooter called Halo.

FRIES Peter Tamte (executive vice president of Bungie) gave me a call out of the blue, just a few months after the Valentine’s Day Massacre, at a time when I was really just starting to look harder around the industry for content. And he told me that Bungie was in kind of financial difficulties. They already had one suitor, Take-Two.

MARTY O’DONNELL (music composer at Bungie) Steve Jobs had just come back to Apple, and he made the first showing of Halo publicly at Macworld in 1999. Next, we started hearing rumors about the Xbox, and we also knew that the PlayStation 2 had come out. I remember sitting around talking to Jason Jones and Alex Seropian, the founders and owners of Bungie, about, “How do we put this on a console?” But we were just like, “Maybe after we released it on the PC.”

ALEX SEROPIAN (co-founder and CEO of Bungie) The studio grew up very independent, and we embraced that kind of underdog mentality. The culture was kind of anti-establishment, not deliberately anti-Microsoft, but the culture was very different.

O’DONNELL I flew the night before the first showing at E3 carrying the only DVD version of Halo. We got into the theater that morning, and Alex Seropian was really happy. And then right after the VIP showing, Alex took me to one side, and he says, “Marty, I know this is crazy, but Microsoft just offered to buy us.”

SEROPIAN I’m not going to lie, there were economic motivations. But you know, our stage had always been the smaller stage in the gaming industry, and here was the idea that we could be a flagship title—and yes, a lot of things had to go right for that to happen.

BACHUS I got a voicemail from Neil Nicastro, the CEO of Midway, saying that we were the dumbest people in the industry, that he could understand maybe not wanting to buy them, but why would we buy a PC game developer? Everybody kind of thought that was dumb. And the guys at Microsoft Japan were like, “We’re not going to even ship Halo because as we all know, as an immutable law of physics, first-person games don’t do well on console.”

O’DONNELL In 2000, we all moved out here. We were in temporary quarters in Redmond, right next to the Expedia people. I can’t even begin to describe the difference in personality between someone who would be a crazy game programmer or artist from Bungie and the super, straight-laced, programming, historian-type, Expedia people. We built our own space, and we said, “We’re going to have electronic locks that only Bungie people can open.” We didn’t even let Ed have a key.

SEROPIAN I remember Ed Fries coming in to the studio, and he asked me, “How are things going for E3?” To which my response was, “I don’t think we should go.” It was one of those conversations where he was like, “Wait a second, did you just hand me a live grenade or something? We cannot not go.” And then we went, and it wasn’t so great.

FRIES The graphics in the machines that we had to show were running at half speed. And Bungie had chosen to demonstrate the multiplayer feature, which they thought was really unique and cool. It’s true that in a show setting, competitive multiplayer is a super fun thing for people to do, where they all walk up and pick up a controller. It’s also one of the hardest things to do from a performance point of view.

BACH When we came back, the Bungie team said, “Go away. Nobody gets to bother us. Nobody gets to come and see the game. We don’t want anybody’s input. Just let us finish.” Effectively, Ed locked down the group and said, “Nobody gets to go talk to them.”

SEROPIAN There was definitely a point where I felt like the game was going to be very good. It was going to be a game we could definitely be proud of.

BACH When we got to the end, they started coming out of their cocoon and started showing it to a few influentials. And suddenly, you realize, “Oh my God, we have a hit.”

FRIES We loved the game internally. But nobody really knew what was going to happen at launch.

AARON GREENBERG (head of business planning) I did the forecasts for all of our games for launch, and Halo was not the top-forecasted title.

BACH People in the industry looked at us like, “Let me get this straight. This thing that you showed at E3 2001, which looked bad and played sluggishly and is in a category that’s never been successful in video game console history, that’s your launch title?”

Putting the Box in Xbox

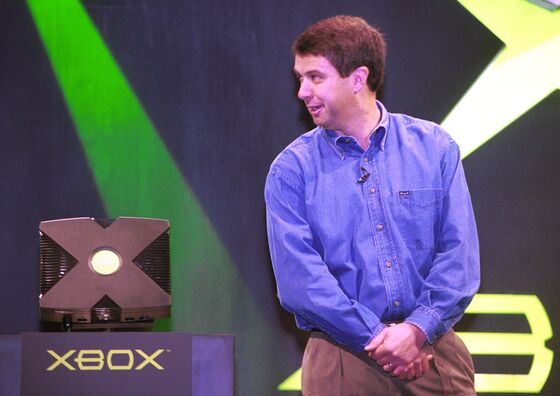

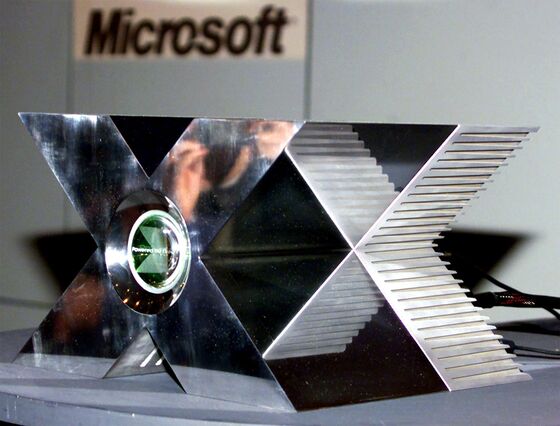

Meanwhile, the hardware team needed to figure out how to turn the prototype Bill Gates teased at GDC, a big silver X, into a product they could mass produce. A month later, Thompson resigned, citing concerns about the project’s costs. His manager, Bach, took over.

THOMPSON I don’t know how you go to work every day, where you build more boxes to lose more money.

TODD HOLMDAHL (head of hardware) The team was less than 20 people altogether that moved over with Rick Thompson. Most of us were so naive about the complexity of it.

BACH We’d made plush dolls, mice and keyboards and reference-design stuff, but never a project like this.

GREENBERG In the old days, there weren’t companies that did tear-downs, so we actually had to take a PS2, we took the entire thing apart, put it on a giant wood board. We did a whole competitive review, and we went through every component, every piece and priced it out and tried to figure out how many screws and how much did it cost.

HOLMDAHL We had to design the product. Then we also had to figure out the manufacturing strategy. And then we had to figure out component-sourcing strategy, all at the same time.

MICHAEL MARKS (CEO of the manufacturer Flextronics) They were very transparent about the fact that they didn’t know what they were doing.

BACH Flextronics says, “We’re going to build a factory for you in Guadalajara.” We didn’t have that before.

MARKS They took advice. They did a better job than many other companies that thought they knew all the answers. I used to come up and have a monthly meeting with Robbie Bach, and we’d play basketball with Steve Ballmer. It was damn early, that game.

BALLMER There was real marginal cost associated with this thing that we didn’t have on our other businesses. The opportunity to make colossal mistakes was much bigger.

MARKS The first version of the hardware had a very high failure rate, 20% or 25%. We had a lot of repair work that had to get done. They just paid for everything, and we just kept iterating until we got it right.

BACH We were having trouble with the DVD drive. The drives weren’t playing a lot of movies, and literally, at one point, we had everybody testing movies. I tested a hundred movies from my movie catalog.

HOLMDAHL We had 200,000 of them that we had to rework. We had to open them up and add felt to them so they wouldn't scratch the DVD.

Still riskier was the team’s decision to add a high-speed internet connection, the first console with that capability built-in, even though the service that used it wouldn’t launch for another year.

BOOTH Some of the rockiest points were around Xbox Live because broadband hadn’t even hit yet. So the big decision we had was, Do we do dial up, or do we go full-on with broadband?

BACH Bill said, “Well, I think that’s a mistake. I don’t think broadband is going to be ready.” I think he said it more strongly than that.

BOYD MULTERER (development manager for Xbox Live) There was one focus group we did that was really influential. It was pure console gamers, and they come in, and they’re like, “The way gaming works is, I invite my friends over, they bring a six pack of beer, we sit on the couch, and we’re going to play FIFA or football.” They distinctly express no interest in playing online against people. We asked, “What happens when you graduate from university?” And they’re like, “Oh.”

ERIC NEUSTADTER (program manager of operations) When I started, there was no lab or anything. Xbox Live, as it existed then, was a computer under Boyd’s desk.

HEIDI GAERTNER (head of user interface for parts of Xbox Live) I worked until midnight every day. The pressure was amazing.

BACH Myspace doesn’t exist yet, right? And so the idea that you were going to have millions of people talking to each other online, where the conversation is as important as the game, was a new idea.

BALLMER It was really pretty early in the world of social. Social was relatively in its infancy, and Xbox was one of the pioneers in really demonstrating the value and importance of it.

PETER MOORE (president and chief operating officer of Sega of America) We felt that their ability to really nail online was going to be key.

Xbox Live pioneered the idea of selling downloadable content after a game's release. Again, EA was a holdout, expressing concern about Microsoft’s monopolistic tendencies.

RICCITIELLO Robbie would call me almost every Sunday for 50 weeks in a row because Xbox Live wasn’t going to be what he wanted without EA.

MATHIEU FERLAND (producer of Ubisoft’s Splinter Cell game) We’d entered into a new philosophy. Usually, when you are shipping a game, the box is shipped, everybody’s on vacation, and we’re thinking about the sequel. But because of Xbox Live, we had this incredible opportunity to come up with extra content.

The console’s design eventually morphed into an oversized controller known internally as the Duke and an even chunkier machine, both in black plastic. The aesthetic choices doomed the Xbox in a key video game market.

GREENBERG In focus groups, consumers in Japan would hold the original Duke controller, and they were like, “It’s so big.” They cared a lot about things being compact. Our mindset was, How do we go build a global console business, but also how do we have success in Japan? We were a little naive about just how challenging that would be.

HOLMDAHL Some might say it might not have been the most aesthetically pleasing. But it was very iconic.

MOORE We always used to call it the Incredible Hulk because it was big and green. But I think also there was the knowledge that this was a company that was going to get it right eventually. That if Gates, Ballmer, et al., were really convinced that this was a market they needed to be in, they had all of the resources, all of the talent, all of the expertise and long-term patience to make it happen.

The Big Reveal

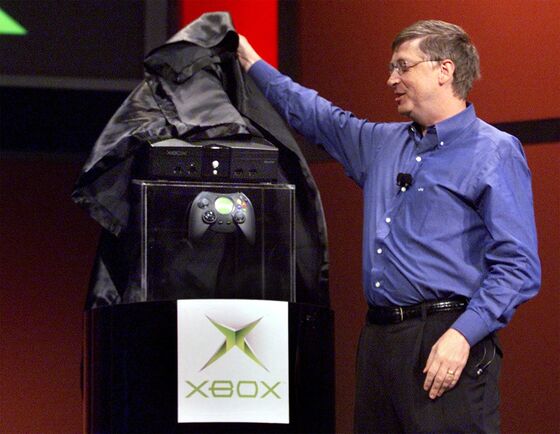

On Jan. 6, 2001, Gates formally unveiled the Xbox as we know it at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. Joining him onstage was Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, dressed a bit like an agent from the Matrix.

CINDY SPODEK DICKEY (manager of national consumer promotions) There was a lifestyle report that showed gamers overlapped with fast food and WWE, so I suggested WWE for CES. Somebody said, “Do you think we could get a couple of the wrestlers onstage?” And somebody else said, “We don’t need a couple. We just need the Rock.”

BOOTH He’s a big powerful guy, and Xbox was a big powerful machine. It was like, “He’s available. It kind of fits.”

BACH They’re rehearsing how we’re going to do the reveal of the box itself. And they had created this contraption, where the box sort of popped up out of the middle of the stage and revealed itself, and it was sort of a bad permutation of a Jack in the Box. The first time we showed it, Bill said the equivalent of, “What the F was that?” And Dwayne Johnson, he’s just laughing. We ultimately just put it on stage in a glass container with a cloth over it.

STEVEN VANROEKEL (speechwriter for Bill Gates) Bill was not a big consumer of pop culture, and I don’t think he knew a lot about wrestling. I had to write the script, and so Brian Hall (a Microsoft manager) and I on Thursday nights, we’d get Gorditos burritos, and we would watch WWE wrestling so that I could get all the catchphrases the Rock was using, you know, like, “Can you smell what the Rock is cooking?” I wanted Bill to land some of those lines.

JOHN O’ROURKE (director of marketing) Microsoft was not seen as an entertainment company. I don’t think we had the street cred for being an entertainment company, compared to a Sony.

BOOTH The good thing about Microsoft is that it may not be cool, but it did mean power.

PHIL SPENCER (head of Microsoft’s kids education software unit) That was one of the adjectives that people would apply to it: powerful.

BLACKLEY I was honest about Microsoft’s reputation. I was honest about the Blue Screen of Death. I was honest about the antitrust. I was honest about the fact that Microsoft had no idea about games. I had a phrase, “the stench of edutainment.” God, they hated when I said that. Microsoft, at that point, still thought games was all about Magic School Bus titles.

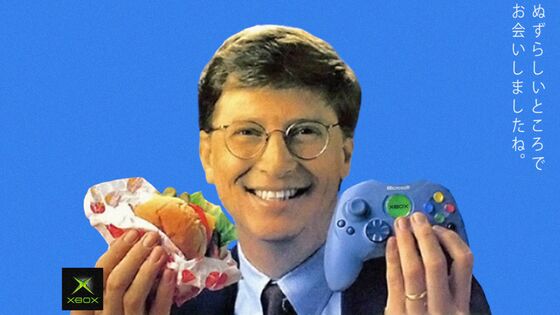

BACHUS We took Bill to the Tokyo Game Show in 2001, and he was like a freaking rock star everywhere that we went. Bill was like, “I want to walk around and look at the show,” and I’m like, “Bill, you can’t go. You’ll be mobbed.” And he’s like, “I'll put on a hat and like, some glasses.” We’re like, ‘They’ll recognize you. You’re Bill Gates, in Japan.”

GREENBERG We had this placemat that had Bill holding what we called the Akebono controller, the smaller controller. And it was the placemat in the cafeteria. It was really just bizarre. You would order your food, and there was this picture of Bill Gates.

BACH 9/11 happened, which threw everything up in the air. People couldn’t travel. So going to Guadalajara to be at the manufacturing facility was actually impossible. And we were trying to get stuff from Guadalajara across the border while the borders got really tight.

SPODEK DICKEY Todd came down the hall all upset because he needed to get something to Hong Kong, but the flights were all messed up. I yelled, “Hey Chuck—Chuck Blevens, who worked for me—do you have a passport?” So we flew him there holding the package, and that’s how we got a piece of hardware we needed shipped out.

HOLMDAHL We chartered a plane from Mexico, and we delivered all these units in the parking lot to jumpstart our testing.

BACH We also had a shipment of Xboxes that were hijacked by somebody. That was pretty exciting.

Release Day

On Nov. 15, 2001, the Xbox went on sale in stores across the U.S. Microsoft held a glitzy event in New York City with Gates to mark the occasion.

O’ROURKE Bill genuinely was like a little kid. You could see it in his eyes. I was the guy that sort of taught Bill how to play some of the games.

BOOTH Don and I were sitting there when we launched at Times Square Toys “R” Us, and we let the first group of 100 in. We were all downstairs, and Bill was coming down by himself on the escalator. He had the Xbox jacket on, and there’s all these 18-year-old skater dudes saying, “Oh my God, that’s Bill Gates!”

FRIES Immediately, the day after launch, it was clear Halo was going to be our runaway hit. What it showed was that we didn’t just create a clone of the PlayStation but that we were opening up a new market that was somewhere in between Mario and PC gaming.

BACHUS Halo was a showcase game. Halo was why you, as an Xbox owner, were smarter than your PlayStation 2-owning friends.

SEROPIAN At no point did I ever think, We’re going to sell 10 million copies. Even months after the release, at no point did we have a sense of the trajectory it was going to get to. Every sort of additional cultural touch point that it achieved was like an oh-my-gosh kind of thing. I remember Tom Cruise’s assistant calling us up looking for some for some help for Tom Cruise with beating a level.

BACH Probably six months after we shipped, you could see the price curve and do the math and know that we were going lose billions of dollars. Nobody knew exactly how much, because we didn’t know how much volume we were going to do. The more volume we did, the worse it got.

BALLMER It certainly paid off in the sense that Microsoft rode the thing in the right direction for it to be a great business.

THOMPSON I was very proud of them when it shipped and pretty quickly ate crow.

ALLARD Most Xbox “origin” stories celebrate heroics, individuals and anti-Microsoft spirit, when in truth any success Xbox had was based in professionalism, teamwork and the Microsoft spirit. The team was the magic behind the Xbox.

RICCITIELLO Microsoft, entering the market as early as they did, was a validation for the industry. Of course, now the industry been validated so many times, it’s the largest form of entertainment on the planet. But back then, it wasn’t that obvious. Bill Gates says so: That matters.

BILL GATES (co-founder of Microsoft) One of my favorite things about Microsoft—and something I still love to do today—was getting to explore big, new ideas that might seem impossible to other people. We built the whole company around that. The early Xbox days were a great example—with a group of people who knew that gaming would be huge, and they believed Microsoft had a role to play even though it would mean starting something completely new.

BLACKLEY It’s a really honest product, and the reason it still resonates is because it stayed honest. Microsoft is a company that was embarrassed by gamers, that thought it was all 14-year-old, criminal skateboarders playing games. We proved them wrong.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.