Tropical Storm Races Toward Louisiana, Curbing Oil Output

Tropical Storm is barreling toward Louisiana and could hit coastline as a hurricane by Saturday, is causing oil prices to soar.

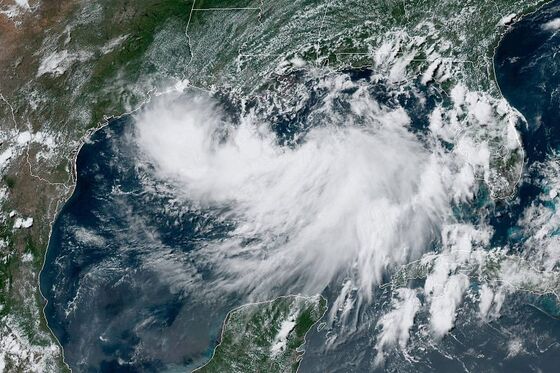

(Bloomberg) -- Tropical Storm Barry is barreling toward Louisiana and could hit the coastline as a hurricane by Saturday, causing close to $1 billion in damage and worsening flooding in New Orleans.

The system, which was about 90 miles (145 kilometers) south of the Mississippi River’s mouth as of 8 p.m. New York time, has already curbed about half the energy output in the Gulf of Mexico and helped lift oil prices to a seven-week high. It’s also prompted Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards to declare a state of emergency, while hurricane and tropical storm warnings and watches are in place along the state’s coastline.

“It is a heck of a water event once again,” Bob Henson, a meteorologist with Weather Underground, an IBM company, said by phone. “We keep hammering that water is a big threat and here we are again. Barry may or may not become a hurricane, but it will be a rain event and there could be surge problems.”

The storm -- with current top winds of 45 miles an hour -- may drop as much as 25 inches of rain in some places, according to an advisory from the U.S. National Hurricane Center. Ship traffic was disrupted in the Mississippi River, where water levels are rising. Companies have cut 53% of oil and 45% of natural gas output in the Gulf.

While New Orleans -- where an emergency was declared Wednesday -- won’t have a mandatory evacuation, residents should be prepared to shelter in place because the slow moving storm could bring heavy rain for 48 hours, Mayor LaToya Cantrell said at a press conference. The Mississippi is now forecast to crest at 19 feet, according to the National Weather Service. That should keep the river below the tops of levees in the city, according to Cantrell.

Louisiana is already under pressure from floods after the months of rain that have set records across the U.S. and prevented U.S. farm fields from being planted. The Mississippi River in the state has been at flood stage since January and, for the first time since Bonnet Carre spillway was completed in 1937, the Army Corps of Engineers has had to open it twice in the same year to help prevent flooding in New Orleans and take pressure off levees.

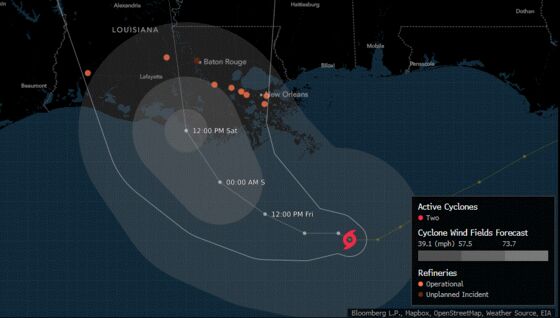

For a map showing assets in the storm’s path, click here

U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude traded above $60 a barrel on Friday, while natural gas futures reached the highest level in almost six weeks on Wednesday.

Gulf of Mexico operators have shut-in 1.01 million barrels a day of oil production because of the storm, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement said in a notice. Almost 1.24 billion cubic feet a day of natural gas production is also closed.

Organization | Impact |

| Chevron | Evacuated Petronius, Blind Faith, Genesis, Tahiti, and Big Foot platforms |

| BP | Evacuated Mad Dog, Atlantis, Thunder Horse and Na Kika platforms |

| Shell | Evacuated Mars, Ursa, Olympus and Appomattox, Auger, Salsa and Enchilada platforms; shut offshore facilities feeding Zydeco crude pipeline |

| Anadarko | Evacuated Constitution, Holstein, Marco Polo, Heidelberg platforms |

| BHP | Evacuated Neptune, Shenzi platforms |

| ConocoPhillips | Evacuated Magnolia platform |

| Exxon | Personnel evacuated from three platforms |

| Enbridge | Evacuating workers from Venice, Louisiana, gas facility after shutting offshore pipeline |

Phillips 66 | Shutting Alliance refinery in Louisiana. Full shut-down to be completed by early Friday morning |

U.S. Coast Guard | Expects to set “condition Zulu” at New Orleans, meaning gale force winds within 12 hours and the port is closed |

Louisiana Crescent River Port Pilots | Suspended operations |

| Cargill | Temporarily closing facilities in Reserve and Westwego, Louisiana |

Port Fourchon | Recommends evacuation |

The Gulf offshore region accounts for 16% of U.S. crude oil output and less than 3% of dry natural gas, according to the Energy Information Administration. More than 45% of U.S. refining capacity and 51% of gas processing is along the Gulf coast.

While the offshore platforms could return to normal operations in a few days, there is a chance widespread flooding could close some refineries and make it difficult for ships to make deliveries across the region, Jim Rouiller, chief meteorologist at the Energy Weather Group near Philadelphia, said by telephone.

“The first impact is to the rigs and platforms, then the second risk shows up on Friday and Saturday to the refinery areas,” Rouiller said. “The thing that is going to be really worrisome is the amount of flooding rains across Louisiana. I think the worst is yet to come.”

Based on its current track, the storm will likely cause about $800 million to $900 million in damage, said Chuck Watson, a disaster modeler with Enki Research in Savannah, Georgia. That could balloon to $3.2 billion if floods overwhelm New Orleans, he said.

A spokesman for the Army Corps of Engineers doesn’t believe levees will be topped by flood waters. The barriers on the lower Mississippi have been inspected daily since November when flooding became an issue.

Shipping is grinding to a halt along the southern reaches of the Mississippi River as deteriorating weather conditions made it unsafe for river pilots to board and steer cargo ships. The heavy rains could hurt cotton crops in southern portions of the Mississippi Delta, said Don Keeney, a meteorologist with Maxar in Gaithersburg, Maryland. Kyle McCann, assistant to the president of the Louisiana Farm Bureau, said there hasn’t been any damage to crops in the state yet, but expects a substantial impact in coming days.

Thunderstorms have already flooded New Orleans streets and the National Weather Service has issued a flash flood watch from southern Louisiana to the Florida panhandle. City pumps had trouble keeping up with the water, which is a “bad sign,” said Enki Research’s Watson.

--With assistance from Shruti Date Singh, Mike Jeffers, David Marino, Jeffrey Bair, Denitsa Tsekova and Sharon Cho.

To contact the reporter on this story: Brian K. Sullivan in Boston at bsullivan10@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Tina Davis at tinadavis@bloomberg.net, Pratish Narayanan

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.