Will Smart Machines Kill Jobs or Create Better Ones?

There’s general agreement that human workers will require more education and skill to keep up with technological change.

(Bloomberg) -- In one vision of the not-too-distant future, robots handle half of all work tasks, leaving legions of humans unemployed and insecure. In another scenario, those same technologies revolutionize rather than reduce opportunities for people, creating jobs that have yet to be imagined. Such are the stakes as a new wave of automation reshapes the workplace, accelerated by the pandemic.

1. Why is this an issue?

Advances in artificial intelligence, or the capability of machines to learn by ingesting large amounts of data, are driving a rethink of what jobs only humans can do. The changeover has already started. Sales of professional service robots -- those used for nonindustrial functions such as logistics, inspections and maintenance -- reached 271,000 units in 2018, up 61% from 2017, according to the International Federation of Robotics. There are now 2.7 million industrial robots operating in factories worldwide, and the federation expects that to increase to 4 million by 2022.

2. Is this something to be feared?

Opinions vary. A 2018 working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research in the U.S. found “a wide range of viewpoints in the public discourse, ranging from alarmist predictions of massive unemployment caused by robots to sanguine predictions about net new job creation.”

3. Which jobs are ripe to be automated?

Store cashier, clerk, telemarketer, paralegal, cook, waiter, receptionist, bank teller, security guard, data analyst, tax preparer and truck driver are among the jobs often mentioned as most susceptible to automation. Less obvious ones include surgeon, accountant and financial analyst. (Even some news reporting is being done by machines these days, including at Bloomberg News.) Jobs requiring repetitive tasks in a structured setting, primarily in manufacturing, were the first to be directly affected by automation, with the auto industry leading the charge. Since 1980, the number of U.S. manufacturing workers has shrunk by a third, to about 13 million, while output doubled. Newer machines come equipped with vision, mobility and the ability to learn. Sophisticated software is able to carry on phone conversations with customers, for instance.

4. How many jobs are we talking about?

As many as 120 million workers in the world’s 12 largest economies may need to be retrained in the next three years as a result of automation and AI, according to a study by International Business Machines Corp.’s Institute for Business Value. The Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program reported that roughly 36 million Americans hold jobs with “high exposure” to automation. In a 2017 report, McKinsey & Co. predicted that as much as 14% of the global workforce -- 375 million people, give or take -- would need to change occupations because of automation by 2030. A lot depends on new technologies that exist but aren’t quite ready for prime time, such as self-driving vehicles. There are about 3.5 million truck drivers in a U.S. workforce of about 160 million.

5. What sorts of jobs could automation create?

It has always been much easier to identify jobs at risk from technology than to predict the new jobs that will be created. Before the advent of the internet and smartphone, it would have been difficult to foresee a need for mobile app designers or social media specialists, much less the emergence of “YouTube influencer” as a well-paid occupation. The World Economic Forum, in a 2018 report, identified machine-learning specialist, human-machine-interaction designer and digital-transformation specialist as among the new roles workers may fill. Forrester Research Inc. mentions roles like botmaster and user-interface designer.

6. What did the pandemic do?

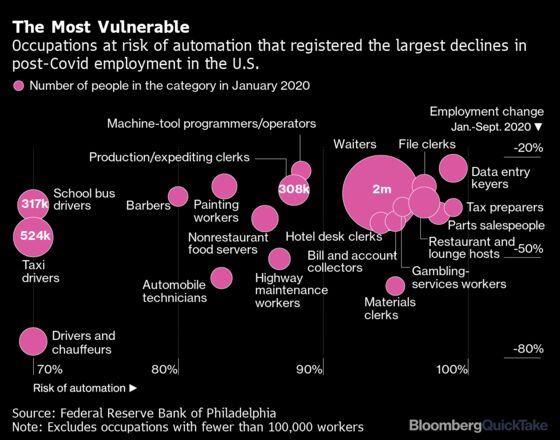

It forced many millions of humans out of work and highlighted an undeniable strength of robots -- they can work side by side without spreading germs. Shutdowns at meat plants because of infected workers pushed companies, including Tyson Foods Inc., to search for robotic-processing solutions. A September paper by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia said pandemic-driven layoffs were higher for occupations that are more susceptible to automation, increasing the risk those jobs will become obsolete. The authors also said Covid-19 may accelerate automation of jobs that can’t be done remotely, such as toll collector, hotel desk clerk and parking attendant. The pandemic also spurred new problems for automation to solve. Honeywell International Inc. began selling a beverage cart-size robot that rolls down an airplane aisle while disinfecting the cabin with ultraviolet light.

7. Is there a way to ease the impact?

There’s general agreement that people will require more education and may have to change occupations more often to keep up with technological change. A 2018 report by the Economist Intelligence Unit gave top marks to South Korea, Germany, Singapore, Japan and Canada for their preparations “for the coming wave of intelligent automation.” The U.S. was ranked ninth out of 25 countries.

8. What’s the case for this being a good thing?

History suggests that the worst fears of machines making humans obsolete don’t come true. In some quarters, AI and robotics are considered the Fourth Industrial Revolution, following other big transformations in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. And while displacement of jobs occurred in each wave of new technology, new jobs emerged to balance out some of the pain. Concern about technology-driven mass unemployment “has proven to be exaggerated” throughout history, University of Oxford academics Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne wrote in an influential 2013 paper. Rather, technological progress “has vastly shifted the composition of employment, from agriculture and the artisan shop, to manufacturing and clerking, to service and management occupations,” they wrote. A World Economic Forum survey concluded that while 75 million jobs may be displaced, “133 million new roles may emerge that are more adapted to” the division of labor among humans, machines and algorithms.

9. What’s the case for this being a bad thing?

This round of automation is different, critics say, because AI threatens not just physical labor but knowledge-based white-collar jobs. Darrell West, founding director of the Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings (and author of “The Future of Work: Robots, AI and Automation”) says the possibility of significant workforce disruption “should be taken seriously.” The median of recent studies, including from McKinsey and Oxford University, show 38% of jobs are susceptible, which could match the upheaval of the Great Depression.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTake explainers on artificial intelligence, machine learning and driverless cars.

- A Stephanomics podcast on how Covid-19 is helping robots take jobs.

- AI makes high-skill U.S. jobs, including finance, susceptible to automation.

- How the ability to grip makes machines capable of a host of new tasks.

- The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Automation Readiness Index.

- A McKinsey report on four fundamentals of workplace automation.

- The 2013 University of Oxford report on the future of employment.

- Paul Krugman says automation of jobs is just a “pseudo-issue.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.