Why It’s Difficult to Find Organic Pork

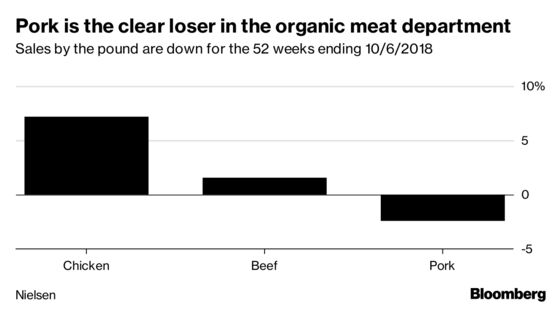

Organic chicken sales are through the roof, but when it comes to pork, sales are bust.

(Bloomberg) -- Though barbecue lovers in Nashville have no shortage of options, many find themselves flocking to a parking lot-based food truck to get their fix.

At the Gambling Stick on Gallatin Avenue, Pitmaster Matt Russo serves locally sourced pork from Porter Road, the butcher shop he parks in front of and once worked at, owned by butchers James Peisker and Chris Carter. Each can tell customers about the high standards for their meat. Antibiotic and hormone free? Of course. Pasture-raised? 100 percent. But organic? Nope.

“The way the pigs are raised is as natural as can be—they have grass, woods, and things to go forage for their natural diet,” Russo said. The result of all that freedom in the great outdoors is a redder, tastier pork. “You just get a much better quality from allowing the pigs to roam and develop their muscles.”

“We don’t have too many people asking, ‘Is it certified organic?’” he said. “We’re a food truck in front of Porter Road. They recognize that that is as good as it gets.”

Even as growth for the overall organic industry continues to outpace total food sales—totaling $49.4 billion in 2017, up 6.4 percent from the year before—and organic shoppers pay premiums for fresh chicken and beef, organic pork sales are slipping, falling 2.4 percent by weight over the 52 weeks ending Oct. 6, 2018, according to data from Nielsen.

Why organic pork hasn’t gotten traction is due to a lack in both supply and demand: Farmers don’t want to spend the additional money raising organic pigs because shoppers aren’t looking to spend it.

Supply Side Restrictions

Organic Prairie, whose products include both fresh and packaged meat, has just 36 U.S. farmer-owners raising pork. Meanwhile, Niman Ranch—the mainstream, marquee name in higher-welfare meat—has more than 600 hog farmers selling under its banner, with none of their pork organic.

The cost of organic feed is usually cited as the biggest obstacle. While chickens live a matter of weeks and need about two pounds of feed for every pound of meat they produce, and organic beef comes from cows that spend much of their lives on grass, hogs live for five to six months before slaughter and require about three pounds of feed for each pound of their meat, sometimes more.

And pricey certified organic feed doesn’t even pay off in the flavor.

“Taste-wise, it’s not going to make a difference if the grain is organic or not,” says Ariane Daguin, owner of high-end meat purveyor D’Artagnan, Inc.

More important, she says, is the animal husbandry, including factors such as the breed of pig and the amount of space it has to move around. Those Porter Road pigs live and roam outside but still get most of their calories from the non-genetically modified organism corn left for them to enjoy at their leisure. And it’s the enjoyment part, says Carter, that makes them so tasty.

There are other difficulties specific to pork. At Gunthorp Farms in LaGrange, Ind., Greg Gunthorp has 200 acres of U.S. Department of Agriculture-certified organic land and a certified organic slaughterhouse. But he doesn’t raise organic pork, citing onerous requirements, compared with those for other organic proteins. Chickens, for example, can begin their organic lives at two days old after being bought from a conventional hatchery. Pigs, however, have to be organic in the womb—their mothers must spend at least their 38 final days of pregnancy living in compliance with organic regulations in order for their offspring to qualify.

Plus, he has no reason to go organic when he can’t keep up with orders as is. “There’s more demand for pasture-raised pork than we can meet,” says Gunthorp.

Jeff Tripician, Niman Ranch’s general manager, says the same thing: “We’re sold out without doing organic.”

Lack of Consumer Interest

On the consumer side, it comes down to cost—and the socioeconomics of food.

Most consumers of pork are in lower income brackets and don’t want to spend more, says Matt Lally, associate director of Nielsen’s Fresh team. Pork has traditionally been seen as a cheap source of protein. “Organic is going to command a higher price than conventional,” he explains, “so is the shopper willing to pay that premium if it’s tending to be lower-income households?”

Niman Ranch occasionally fields inquiries from grocers about going organic, says Tripician, but he tells them it would increase their price so much, they’d have to charge consumers more than double their already high prices. “And they say a resounding ‘Hell, no,’ and that’s the end of the conversation,” he says.

The Organic Trade Association sees price as the biggest impediment to growth as well. “There’s a straight line between cost of production, cost at retail, and the amount consumers purchase,” says Angela Jagiello, associate director of conference and product development.

Growth Opportunities

There is, however, a sandwich-shaped bright spot in the organic pork sector. At Applegate Farms, the organic and natural meats brand owned by Hormel Foods, sales of organic deli ham is booming—bacon, too. While organic sales are up across the board, they are doing especially well in pork, growing at nine times the rate of the naturals line, according to president John Ghingo.

Keeping up with that demand, however, requires looking to Canada’s DuBreton, North America’s largest organic and “certified humane” pork producer, and Field Gate Organics.

“It is a challenge to supply organic pork,” says Ghingo. For Applegate, which requires third-party animal welfare certification as well, it’s even more difficult. “There just aren’t enough organic-, animal welfare-certified producers in the U.S. to supply the quantities we need.”

Even what is produced doesn’t always get sold; once you’ve apportioned parts for organic deli meat and organic bacon, there’s still a whole organic pig to contend with. Current conditions mean some producers end up putting unsold organic cuts on the conventional market, says the trade association’s Jagiello.

Ghingo guesses there might be an intimidation factor, even among the better-heeled. It’s easier to grab a slice of ham and slap it on some bread than risk ruining a very expensive tenderloin. “There’s more preparation required,” Ghingo says.

Still, at least a handful of producers are doing well enough to stay in business and remain optimistic about the future. “We just spent over $60,000 putting up a hoop barn,” says Ron Rosmann of Shelby, Iowa, an Organic Prairie supplier, referring to a naturally ventilated housing structure often seen on non-conventional farms. “We know we can make money.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Justin Ocean at jocean1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.