Why China’s Been Changing Its Mind About Billionaires

Xi’s government has stepped up scrutiny of how wealthy earned their money, and even apparently well-connected tycoons have fallen.

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&w=200)

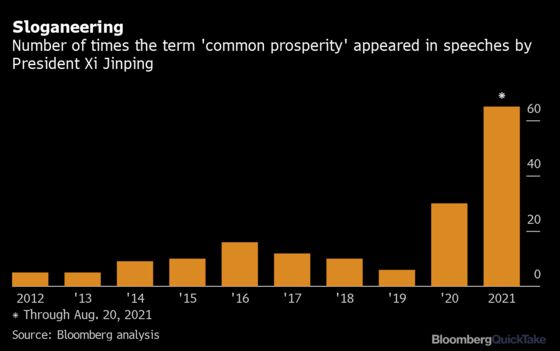

(Bloomberg) -- Chinese President Xi Jinping’s newfound emphasis on promoting “common prosperity” to deal with the large wealth gap in the ostensibly communist nation has led to tough times for some of China’s billionaires. Jack Ma, formerly the richest person in the country, is among those whose net worth has fallen as a wave of new state controls and regulations drove down share prices for some of China’s hottest companies. The government’s campaign is about more than reducing inequality, however. There’s also increasing concern in Beijing about great wealth translating into political power separate from the Communist Party.

1. How many billionaires does China have?

Of the 500 richest individuals globally on the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, 81 are Chinese with a combined fortune of $1.1 trillion. That’s second only to the U.S., where 162 billionaires hold a combined $3.4 trillion. UBS Group AG estimates the world’s second-largest economy had more than 380 billionaires last year, and that this wealth pool had grown tenfold since 2009. Another ranking, the Hurun Global Rich List 2021, counts more than 1,000 billionaires in China, the most in the world.

2. Why has the Communist Party let people get rich?

It’s a necessary evil. The party identifies among its core tasks the advancement of the fundamental interest of the greatest majority of Chinese people. Four decades ago, then party patriarch Deng Xiaoping (who famously said poverty is not socialism) interpreted that to mean that it was OK if some people needed to get rich to improve the livelihoods of the masses. Since the introduction of his drastic economic reforms, more than 800 million people have been lifted out of poverty in China. Deng’s successor, Jiang Zemin, allowed entrepreneurs to join the party in 2002. That helped legitimize their position in society and gave them some say in the country’s governance -- many are members of the parliament or its advisory body -- while also tying them closer to the party.

3. So the party supports personal wealth?

It’s complicated. The party supports private business and the entrepreneurial spirit as a driver of economic growth and job creation. It’s far more ambivalent about personal wealth because of the growing income gap between rich and poor, which is not very communist. Xi’s government said it wanted to reverse that growing gap in 2017, but despite some progress the distribution remains very unequal. There is also increasing concern within the party about threats to its monopoly on power, as fast-growing private companies -- and their super-rich owners -- gain more sway over segments of the economy such as social media and the financial system.

4. What’s it doing now?

Xi’s government has stepped up scrutiny of the wealthy and how they run their companies. It has unveiled a barrage of regulatory and antitrust actions, many targeting Big Tech. Ma’s fintech darling Ant Group was forced to abruptly scrap a $35 billion mega-listing last year after he publicly blasted China’s financial system and its regulators. His e-commerce platform, Alibaba Group, was fined a record $2.8 billion in April for abusing its market dominance. Wang Xing, founder of food-delivery giant Meituan, was summoned to a meeting in Beijing and told to keep a low profile after sparking a social media furor by posting a millennium-old poem some interpreted as anti-establishment.

5. How are the billionaires reacting?

Some, like Ma and Wang, are avoiding the spotlight. They also are showcasing their charitable side, donating billions of dollars to promote “common prosperity.” Zhang Yiming, founder of TikTok-parent ByteDance Ltd, said he would step down as CEO at the end of this year to focus on other areas including “social responsibility.” Pinduoduo’s Colin Huang stepped down as chairman of the e-commerce company in March, while also pledging $100 million to his alma mater to support scientific research. Online gaming giant Tencent Holdings Ltd, chaired by Ma Huateng, pledged $15 billion in social aid for a “sustainable social values” program in August.

6. Are they the only target?

No. The government has gone after after-school tutoring companies, forcing some to go non-profit to help reduce the financial burden on ambitious parents. Taxation might play a role in narrowing the wealth gap. Although it’s been talked about for years, a tax on residential property is meant to be introduced during the current five-year plan that ends in 2025. With many in China putting their savings into property, a tax on real estate could not only help redistribute some of that money but also could discourage speculation in the property market, making housing more affordable.

7. So is China really communist?

Officially, China views communism as a modern-day utopia: Everyone would collectively own the means of production, all citizens would work for the common good, everybody would be equal and wealth would be distributed based on need. The party’s constitution states that its “highest ideal and ultimate goal is the realization of communism.” That can be seen in the speech Xi gave on the party’s 100th anniversary: “Marxism is the fundamental guiding ideology upon which our party and country are founded,” he said, adding it would achieve “lasting greatness” for China. Getting there, though, is a progression through “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” a phrase Chinese leaders use to describe how they have adapted capitalist market principles into the economy.

8. What does that look like?

China achieved one big goal this year -- “building a moderately prosperous society” -- by doubling both the size of the economy and people’s income and officially eliminating extreme rural poverty. The next step is to realize “socialist modernization,” which Xi has set out to do by 2035. In a speech in 2017, he said that would mean China is a global leader in innovation, the rule of law would be in place and Chinese culture would have greater appeal around the world. People would live comfortable lives, everyone would have access to basic public services and income disparities -- particularly between urban and rural areas -- would be significantly reduced. The environment would be fundamentally improved as well. In his July speech, he elaborated a little:

“We will develop whole-process people’s democracy, safeguard social fairness and justice, and resolve the imbalances and inadequacies in development and the most pressing difficulties and problems that are of great concern to the people. In doing so, we will make more notable and substantive progress toward achieving well-rounded human development and common prosperity for all.”

What that “common prosperity” is and how it will be achieved are unclear. But from there, the party aims to build a “a prosperous, democratic, civilized, harmonious and beautiful modern socialist country” by 2050. After that, communism would be next.

The Reference Shelf

- English-language version of the Constitution of the Chinese Communist Party.

- Bloomberg Billionaires Index tracking the world’s 500 wealthiest individuals.

- A QuickTake explainer on the empire Jack Ma built.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Andrea Felsted and Anjani Trivedi examine what ‘common prosperity’ means for the luxury industry in China.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg