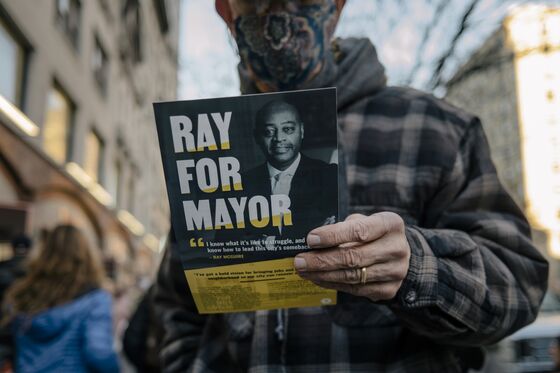

Ray McGuire Wants to Swap Citi for City Hall. It Won’t Be Easy

Ray McGuire Wants to Swap Citi for City Hall. It Won’t Be Easy

(Bloomberg) -- Ray McGuire, one of the most successful Black bankers on Wall Street, had something to tell his friends.

It was September 2019, and seated around a table at the Manhattan home of ViacomCBS Inc. board member Charles Phillips was a small group of Black executives who had made it to the top of corporate America. McGuire, then vice chairman of Citigroup Inc., said he was thinking of joining the race to become New York’s next mayor.

Phillips uncorked a 2010 Napa Valley Reserve cabernet. Bankers Bill Lewis and Fred Terrell raised a glass. Ken Chenault, who ran American Express Co. for nearly two decades, offered a word of caution. He told McGuire his lack of name recognition would be a problem, and not his biggest one. “You’re from Wall Street,” Chenault said, taking on the voice of a skeptical voter. “What has this guy done for us?”

McGuire, raised by a single mother in Dayton, Ohio, before getting three Harvard degrees, pushed back. “This is what I dealt with, and you’re going to tell me that I’ve forgotten that? I haven’t forgotten that,” he said. “I shouldn’t be penalized for my success.”

“I get it,” Chenault recalls saying. “It’s still going to be a big challenge.”

When McGuire left Citigroup last fall to launch his campaign, that challenge was greater than he and his pals could have imagined. Plagued by growing inequality, New York faces the effects of a crippling pandemic: unemployment above 12%, more than $5 billion annual budget shortfalls for the next few years and deserted business districts.

Now, three months into his campaign, and three months before the June 22 Democratic Party primary, McGuire is far behind in the polls. He has raised $7.4 million, enough to keep him going, but he’s trailing two other Black candidates, a bunch of established politicians and former presidential contender Andrew Yang, who’s leading the pack of more than a dozen people seeking to replace Bill de Blasio as mayor of the largest city in the U.S.

McGuire has staked his campaign on the belief that New York needs a leader who can bridge two unequal worlds — “from the streets to the suites,” as he puts it. He’s betting that an outsider who became a consummate insider can connect to voters. It’s a message the 64-year-old candidate has so far struggled to communicate. To win, he’ll need to do more than channel the charisma that made him a beloved mentor on Wall Street or the fire that helped him thrive in an industry where so few people look like him. He’ll have to show a city in agony that after decades of megadeals and fancy meals he can cross back over.

It takes only a few weeks in his new role as a politician to see how prescient Chenault’s warning was. McGuire’s career on Wall Street was remarkable. But turning that into votes is proving harder than appealing to executives.

That’s what brings him to Reverend Al Sharpton’s National Action Network headquarters in Harlem on a Saturday morning in February. Sharpton, hailed as a civil rights leader by some and criticized as a self-promoter by others, is being wooed by politicians who want the votes of his followers. This morning, all the socially distanced chairs are taken.

At six-foot-four, with a shaved head and a dark gray suit, McGuire cuts a striking figure. But when he steps to the podium, the energy drains out of the room. He stands unsmiling, reading from notes, his fingers interlaced. “No justice, no peace,” he says, echoing Sharpton’s motto.

The crowd offers a smattering of applause when he demands “better policing.” There’s none when he recites his plan: “Respect, Accountability, Proportionality,” which sounds a lot like “Courtesy, Professionalism, Respect,” the words on the side of police cruisers.

McGuire served on the board of the New York City Police Foundation, which raises money to buy law enforcement equipment and pay rewards for anonymous crime tips. He has rejected calls to defund the police, a rallying cry after last year’s killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and when videos showed New York officers beating demonstrators at protests. McGuire says he would take a hard look at the department’s budget and supports ending qualified immunity for officers to make them personally liable for their conduct. Still, he signed a letter in 2019 criticizing water balloon attacks against police.

Sharpton, who has hosted other candidates, including former MSNBC personality Maya Wiley, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams and Yang, has yet to endorse anyone. He’s known McGuire for years but says his lack of name recognition is a big liability in a race without much in-person politicking. “Not many people know who he is and what he stands for,” Sharpton says. “He came up from dire conditions and became this guy. He’s got to tell that story.”

One person who has endorsed McGuire is onstage: Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, the unarmed Black man whose 2014 death in a police chokehold helped ignite the Black Lives Matter movement. She had just given McGuire a much-needed boost by backing him. “He’s not yet tainted as a politician,” Carr says. “If he becomes the next mayor, I think he could run this city effectively.”

AniYa Antenor, a motivational speaker who had been sitting near the front, isn’t so sure. She says she likes McGuire but is also considering voting for Wiley. “Man,” she says, “it’s so hard.”

Before he leaves, McGuire peels $100 from a wad of cash in his suit pocket and passes it to Sharpton’s donation box. His wife, the lawyer and writer Crystal McCrary McGuire, sends the same amount from her seat.

The story Sharpton says McGuire needs to do a better job telling begins on a dead-end street in Dayton by a paper mill. When its sulfuric stench leaked in through closed windows, he stuck his head into the fridge for clean air. “I know what it’s like to wash tinfoil,” he tells congregants at Maranatha Baptist Church in Queens Village the next day. “I know what it’s like to get those small ends of bars of soap together and convince yourself you have a full bar.”

When McGuire distinguished himself in the classroom, one teacher encouraged him to attend a mostly White school in the suburbs. Eventually, another teacher sent him East with a list of prep schools to visit.

He got into the Hotchkiss School in Connecticut. The kids in their neatly pressed Lacoste shirts dazzled McGuire, and they were drawn to the teenager who crooned the periodic table of elements as he studied chemistry while keeping a Life Savers lollipop in his mouth.

At Harvard, McGuire majored in English, then earned an MBA and a law degree. To this day, he’s probably the only dealmaker who quotes “the great philosopher Epictetus” (“only the educated are free”) as well as “one of the great philosophers of the 20th century, James Brown” (“I feel good”).

His first Wall Street job was at First Boston, the epicenter of the 1980s mergers frenzy. The deals he worked on included several in the paper industry. The smell now was of money. When star bankers Joe Perella and Bruce Wasserstein left in 1988 to start their own firm, McGuire followed.

After stints at Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley, McGuire joined Citigroup in 2005 as co-head of its investment bank. He was in charge for more than a decade, working on some of the biggest mergers in corporate America, including multibillion-dollar deals for the Koch brothers, Saudi Arabia’s state-owned chemical company and the tobacco industry.

But his most important task at Citigroup was rebuilding the investment bank after the financial crisis, which crippled the company and led to a $45 billion government bailout. McGuire’s unit wasn’t responsible for the tsunami of losses that swamped Citigroup. “I didn’t have anything to do with that,” he told mayoral candidate Shaun Donovan, who jabbed him at an online debate in January.

Still, the investment bank took a hit. McGuire lured top talent and focused the unit on a few industries, including financial institutions and energy, where the bank still dominates. In 2018, his last year at the helm, it had $5 billion in revenue, a 31% jump from 2010.

McGuire glosses over his four decades on Wall Street at the Queens church, saying he left a “good job” to run for mayor. Congregants shower him with amens, and the sound of tambourines fills the one-room chapel. “I’m not looking for a promotion,” McGuire says. “This is a walk of faith.”

On Wall Street, McGuire was an executive in a company whose percentage of Black employees in the U.S. fell each year for a decade, despite his efforts to mentor and promote colleagues. But his race wasn’t the only reason he stood out. He was widely liked, pulling in bankers and clients by repeating their names in the middle of sentences, remembering relatives, sprinkling in French and showing off his jump shot.

One colleague found his low and steady voice so comforting she listened to his speeches online when she felt down. In a conference room, he had a magic for coming across as a quiet man making a choice to summon his energy and direct it toward whomever was speaking. His attention felt expensive, yet he seemed to enjoy giving it to all kinds of people, a quality politicians need. When he left the bank in October, his last memo bid farewell to four baristas in the lobby cafe and three maintenance workers.

“You need a business leader in this job — all the rest of the stuff is interesting, but people need to have an economy that works,” McGuire says on a Zoom call from his Central Park West duplex on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. There are rows of leather-bound books in a bookcase and paintings by prominent Black artists on the walls. “We’re going down together. You know what? There ain’t no Plan B, there’s no cavalry coming. If we don’t get it done, it ain’t going to get done.”

One pitch from his Wall Street friends goes like this: After two terms of a progressive mayor, New York needs to pivot back to corporate leadership, something closer to what it had during the 12 years when Michael Bloomberg, majority owner of the parent company of Bloomberg News, was in City Hall. McGuire calls it a merger of Wall Street and Main Street.

Convincing New Yorkers they need a banker to save the city won’t be easy. This year’s primary is a battleground of political machines, influential unions, five distinct boroughs, ascendant progressives and a deadly pandemic that makes it unthinkable to pump a stranger’s hand.

Then there’s the wild card of ranked-choice voting, being used for the first time to choose a New York City mayoral nominee. That means voters can pick as many as five candidates in order of preference, and someone who gets enough second-place votes, even if they don’t finish first, could come out on top. No one knows how that will play out.

McGuire has no political record to run on, and didn’t even vote in the last mayoral primary or election. His launch video was appealing thanks to the compelling arc of his life story, shots of him running in black-and-red Air Jordans through the emptied streets of Times Square, a voiceover by family friend Spike Lee and jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis on the soundtrack.

But it didn’t show what’s driving him to run. He has no trademark policy like Yang’s call for cash relief for low-income residents or Comptroller Scott Stringer’s environmental plan.

McGuire says the skills he honed on Wall Street will help him deal with what the pandemic has wrought. Even with the federal rescue, spending will be constrained at a time when more than a half million residents have lost jobs and there’s rising need to help with food and housing. State finances are tight, too, which could mean a pullback in the funding that accounts for about one-sixth of city revenue. “The city is broke and broken on the watch of others,” he says.

McGuire’s plan for a comeback is full of ideas you might hear wafting down the halls of a bank. He proposes relief for property owners in exchange for lowering rent and “calling in every favor” from businesses and philanthropists to provide loans and grants. He wants more borrowing, private investment to fuel infrastructure projects and deregulation to allow for faster permits. He promises to bring back 50,000 jobs by covering half of a worker’s salary for a year and suggests a $50 million loan fund for businesses owned by minorities and women.

But first he has to introduce himself to voters like Alfonso Wright, owner of Brooklyn Tea in Bedford-Stuyvesant. “I know he’s a Wall Street guy,” says Wright, 39, whose business is hurting. “If a person can’t afford his house, he can’t afford to buy my tea.” Wright, who cares about ending police violence and climate change, says he didn’t realize McGuire is Black until January. “It may mean that he understands the struggles,” Wright says. “But it doesn’t change my view of him until I hear his policies, his stances and how he talks about his success.”

McGuire will also have to win over skeptics, like United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew, who doesn’t like the candidate’s past support for charter schools. He didn’t convince Henry Garrido, who runs District Council 37, the city’s largest public employee union. “Business people often fail at understanding much about political leadership and how government works,” says Garrido, who has endorsed Adams. “If you approach disenfranchised people as if you were a business, you would immediately cut them off from any safety net.”

If McGuire is having trouble getting his footing on the streets, it’s been the opposite in the suites. About 100 former Citigroup colleagues, dozens of employees at rival banks and billionaires including Bill Ackman and Leonard Lauder have helped him raise more money than most of his rivals. Adams and Stringer also have sizable war chests, but that includes public financing, which McGuire has declined. A super PAC called New York for Ray has pulled in an additional $3.2 million, including contributions from financial crisis figures Dick Fuld and John Mack.

Other donors include colleagues from the boards of the Studio Museum in Harlem, Lincoln Center, the New York Public Library and the Whitney Museum. Some of those friends have been living in a different city than many New Yorkers. Most got a windfall thanks to the government’s trillion-dollar support for markets. This year’s election offers them another opportunity. It’s not just that they fear a push to tax rich people and their corporations. In this crisis, what many wealthy New Yorkers demand isn’t free health care, paychecks for all or defunding police. They crave efficiency and performance.

McGuire’s success in the suites is reflected in a recent online poll of readers of Crain’s New York Business, which pegged him as the front-runner. But an Emerson College poll of likely Democratic voters in early March showed him in eighth place, at 3%. It’s still early in the race, and a lot can happen between now and June. McGuire’s campaign is expecting a boost from about $750,000 in ads on cable news networks, local stations and radio, and there’s more spending on the way, says spokeswoman Lupe Todd-Medina.

Chenault, who raised a word of caution back in September 2019, says his friend will have to show the city the depths of his empathy if he wants to win. The former American Express boss, who contributed $250,000 to McGuire’s super PAC with his wife Kathryn, has been watching his peers try to go into politics for decades. The two fields, he warns them, are not the same. When those friends tell him New York should be run like a business, he says it depends.

“At the end of the day, when a policeman is shot, when someone’s apartment is broken into, what’s the business example?” Chenault asks. The way he sees it, running City Hall is more like becoming a minister to millions. “You’re taking care of the flock.”

— With assistance from Henry Goldman and Sonali Basak

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.