(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A JPMorgan Chase & Co. study of more than 25,000 transcripts of conference calls held by companies in the S&P 500 index, released a few weeks ago, showed concern among business executives about geopolitical risks climbing to the highest level in five years. From rising global trade tensions to President Donald Trump tweeting to OPEC about oil prices, financial markets are increasingly swayed by developments in politics rather than economies.

Dominic Armstrong aims to profit from those risks. After a career in banking, he co-founded Aegis Defence Services in 2002 with former British army officer Tim Spicer, and ran its intelligence arm. The private security firm, which had military contracts including a three-year deal with the U.S. Department of Defense to oversee its reconstruction program in Iraq, was bought in 2015 by Montreal security services company Gardaworld.

In 2017 Armstrong launched The Horatius Fund to invest in dollar-denominated bonds sold by emerging market borrowers. The fund “utilizes a global network of intelligence experts and professional specialist sources to identify and analyse investment opportunities where political risk has been mispriced,” according to its marketing material.

Named after a Roman army officer who defended a bridge against the Etruscan army in the 6th century BC, the Horatius Fund oversees about $50 million, of which about 75 percent is in corporate debt with the remaining 25 percent in sovereign bonds. I caught up with Armstrong by telephone last week. Here’s a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

MARK GILBERT: Give me an example of an investment you’ve made where you think the market was mispricing the bonds of a particular country or issuer.

DOMINIC ARMSTRONG: One that really stood out to us last summer was Bahrain’s sovereign debt. Those analyzing emerging markets tend to be developed-market specialists; therefore they bring developed-market skills to bear, i.e. spreadsheets, models and huge amounts of financial analysis. In Bahrain, that analysis said “The country doesn’t produce enough oil to cover the cost of running the economy.” So bonds with 7 percent coupons were offering yields of 9 percent, which gradually rose to about 9.9 percent. We started picking those up on the basis there was a sort of implicit guarantee that Saudi Arabia would back Bahrain not least because they didn’t want some kind of Shia, Iranian outlet on their borders. On that basis it seemed clear that Bahrain was pretty well underwritten even if it didn’t show up on a spreadsheet. In early September, Saudi Arabia explicitly came out and guaranteed those bonds, so the bonds settled down to much more sensible 7 percent yields. That was a very attractive trade that came good.

MG: Why the focus on hard-currency debt rather than bonds denominated in local currencies?

DA: That comes from hard experience. I was the head of research for Jardine Fleming in Southeast Asia in the 1990s, when the currency crash that began in Thailand became a great contagion. I watched the Indonesian rupiah go from 2,500 to the dollar to 16,000 to the dollar in about 10 days. There are occasions when the right local currency gearing can give you extra performance, but you’re living with another dimension of risk. There’s so much opportunity in dollar-denominated debt around the world; we don’t feel we need to play that local currency game. I watched how value can be absolutely destroyed, and I don’t believe we need to expose our investors to that additional risk over and above the inherent emerging-market risk where you’re not dealing with pure financial fundamentals; there is a political and a cultural dimension that isn’t always picked up.

MG: Are there countries you avoid in the portfolio?

DA: Being a geopolitical fund, we like to take account of political risk as a primary factor. There are certain countries where a culture that perhaps might treat debt as a political weapon are to be avoided. Russia, in light of its current relationship with the West, is somewhere I would be inclined to avoid unless there was an exceptional yield available and exceptional transparency about the borrowing entity involved. I wouldn’t want to find that our funds were being used as a political football, as part of withholding coupon payments as a political tool.

MG: Can you give me an example of an investment that went wrong because of an unforeseen shift in the political landscape?

DA: When Imran Khan was elected president of Pakistan, there was a huge surge of hope. That surge overlooked the scale of the problems that Pakistan had to face. We believed a degree of reality would creep back into the pricing of the bonds, so we shorted the bonds. We were caught out when Saudi Arabia announced a cash injection into the Pakistan economy. Sentiment was not going to come our way in the wake of such a significant cash inflow, so we closed out that position.

MG: At a loss, obviously?

DA: A couple of points. We walked away before we took too much pain on it.

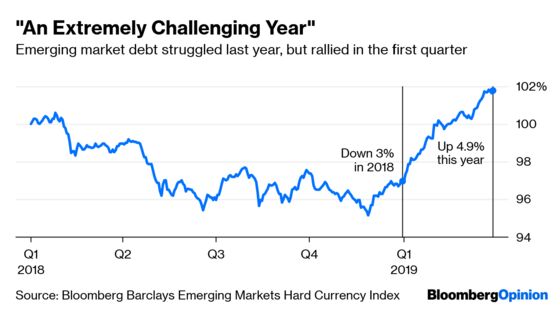

MG: Last year was pretty tough for emerging-market debt. How did the fund perform?

DA: It was an extremely challenging year. Overall, we were down 4.9 percent last year, which was galling given we only launched in 2017. It could have been worse: There was a vortex at the minus 12 percent to minus 15 percent level that some of the benchmarks were hitting. The psychological damage of the market sitting watching blood on the screens every single day led to such a pervasive negative mood. The message from last year is while there was shaken confidence with rising rates and a strengthening dollar, emerging markets held their nerve.

MG: So what’s the start of this year been like?

DA: We bounced back strongly. We were up 3.2 percent in January, another 2 percent in February, March looks like it’s up another 0.5 percent or so. What happened last year, babies and bathwater were all thrown out together because people simply sold down their emerging-market positions. There were some astonishing healthy gurgling babies lying there on the bathroom floor; our job was to go and pick them up at some very interesting prices.

MG: Looking ahead, what are your hopes for growing the fund?

DA: We have one anchor investor that’s pledged $50 million which they will put in at a rate of 33 percent of AUM. We have five discussions going actively with major institutional investors which I hope will see us comfortably over $100 million by the end of the year. The strategy runs to $800 million to $1 billion, so it’s not a huge fund but it’s one that can remain relatively agile, and with that nimble nature should be able to outperform at that level. That’s the three- to five-year aim.

Because we have this large network of ex-government officers in certain walks of life who can give astonishing cultural insights into places, a number of funds are looking at us as offering an interesting edge, because it takes an entire career to build that sort of network.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at jryan13@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.