(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Throughout the 2016 Brexit referendum campaign and at many points during the Brexit debates that followed, a free trade deal with the U.S. was dangled by Brexiters as the prize that beckoned if only they’d hold their nerve. That prize may soon be there for the taking, but the closer it gets, the less impressive it looks.

This week Boris Johnson’s government published a weighty document setting out the U.K.’s objectives for a deal that would bring “better jobs, higher wages, more choice and lower prices for all parts of the U.K.” Donald Trump welcomed the start of talks, enthusing about the “fantastic and big” trade deal the two countries will do. In reality, it will probably be neither.

The overall impact of a trade deal can only be described as modest. In the best of the two scenarios set out in the U.K. paper, a free-trade agreement would add 15.3 billion pounds ($19.8 billion) to the U.K. economy over 15 years, or a 0.16% boost to GDP. For the U.S., the elephant in this negotiation, the rewards require a magnifying glass — the best-case scenario delivers a boost of five-hundredths of a percent of GDP.

That’s not to say a trade-opening agreement isn’t worth having. The two economies are closely linked, with 19.8% of U.K. exports going to the U.S. and 221 billion pounds of trade between them. Each employs more than 1 million of the other’s workers. And in this age of protectionism, even small measures to reduce trade barriers are to be applauded.

For both countries, however, the chief motivation is political. Johnson sees the U.S. deal as the first major purchase using Britain’s much-vaunted Brexit dividend, sovereignty. Should trade talks with the European Union break down, as is very possible, the U.S. ones offer a handy distraction. While Johnson has been clear that no deal with the EU is better than a bad deal, almost any deal with the U.S. will do, so long as Britain’s carefully protected National Health Service isn’t on the table. For Trump, an early supporter of Brexit, an agreement with Britain is a way of widening Washington’s sphere of influence and countering the EU’s trade juggernaut.

While Johnson has gushed about potential trade benefits for a range of goods from Welsh lamb to Scottish salmon, ceramics from Stoke and cars, it is in the services sector — which is more than 80% of the U.K. economy and 46% of the country’s exports — that Britain clearly hopes a deal will provide real market-opening benefits. It’s a good goal, but Britain’s negotiators will need a crowbar and a measure of luck to get what they want there.

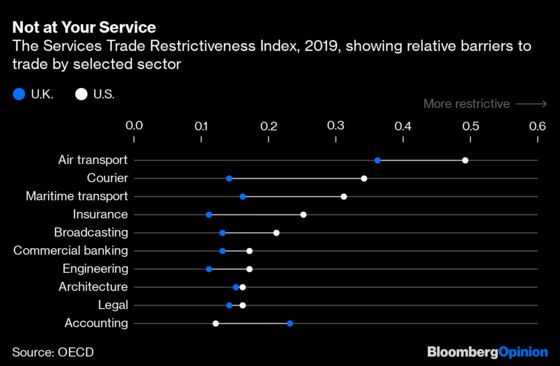

The U.S. is very good at throwing regulatory obstacles in the way of foreign service providers. Measured by the OECD’s Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), the U.S. puts up more non-tariff barriers than the U.K. across a number of services areas, from air and maritime transport to legal services, commercial banking and logistics. The U.S. has more barriers to trade than the average advanced country in 18 out of the 22 services sectors that the OECD measures.

The costs of these barriers — ranging from a tax equivalent of about 3% on road freight transport to 40% in broadcasting — exceed the average tariff on goods most of the time. These are amplified for small- and medium-sized firms, as compliance with regulatory hurdles imposes an additional 12% cost on them compared to what large firms face. Here’s a sense of the gap in barriers for services between the two countries in 10 sectors:

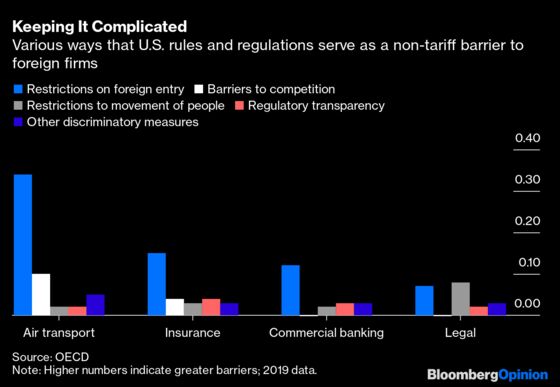

These barriers come in different guises, from restrictions on foreign entry into the market to licensing requirements. As former Tory MP Chris Leslie correctly noted, many appear at state level. For example, lawyers coming to the U.S. must pass local bar exams (though since 2016 foreign attorneys can get temporary authorization to practice law in New York). In the U.S. maritime sector, the chief executive, board chairman and a majority of directors must be U.S. citizens. For U.S. air transport firms, 51% of the non-voting shares and 75% of voting equity must be held by U.S. citizens. Those restrictions are jealously guarded by industry lobbies.

Even with two highly motivated trade partners, there are plenty of areas of disagreement where Britain will come under pressure. Johnson has said repeatedly that the NHS “is not for sale,” but finding a way to liberalize pharmaceutical pricing and lengthen patent protection have been key American demands. So is opening the British market to American agricultural products and lifting a ban on chlorine-washed chicken. Trump will likely also put pressure on Johnson to water down the digital services tax that comes into force in April.

The U.S. election also complicates the calculations. Trump could lose, jeopardizing the likelihood of any deal he approves to get through. Or he could back away from a concession that carries domestic political costs out of fear it would anger his base. Trade talk is not usually dinner table conversation, but contentious issues – whether pharma or chicken – can blow up.

Meanwhile, disagreements over Huawei, policy toward Iran and other issues are a reminder that however special the relationship with the U.S., interests are not always aligned. Trade negotiations also have a habit of simply getting dragged out. Johnson has again postponed his visit to Washington, now due this summer. One way or another, he may eventually have a trade deal to announce, but many will wonder what all the fuss was about.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Nicole Torres at ntorres51@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael writes editorials on European politics and economics for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.