The Myth of Donald Trump’s ‘Beautiful Clean Coal’

The Myth of Donald Trump’s ‘Beautiful Clean Coal’

(Bloomberg) -- Thick white smoke tinged with a silvery hue blows from the chimney of one of the cleanest coal plants in the world.

Designed by General Electric Co. and run by the German utility Energie Baden-Wuerttemberg AG, this facility in Karlsruhe on the banks of the Rhine River is at the heart of a debate about whether coal can ever be clean enough to work in a world fighting climate change.

While the unit produces enough electricity for 912,000 homes, it also devours 250 tons of coal per hour, leaving it a substantial emitter of greenhouse gases. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government is considering proposals to close Germany’s remaining coal plants by 2030—even the cleanest of them. Manufacturers and utilities are hitting back with more efficient technology that makes the most polluting fossil fuel a little less dirty.

“If you look only at CO2 emissions as a data point, then of course we should stop burning coal,” said Michael Keroulle, chief commercial officer of GE Steam Power, a unit of the Boston-based conglomerate that’s selling coal technology. “But the reality is that countries need access to secure, reliable energy, and renewables can’t always provide that.”

The GE plant near EnBW’s headquarters in Karlsruhe, about 90 miles south of Frankfurt, is one of more than 300 plants worldwide tagged as “clean coal” by the industry. They represent about 12 percent of the power produced by coal around the world, according to data from the S&P Global Market Intelligence World Electric Power Plant Database, Platts.

That’s raised alarm among environmental groups, who point to scientific research suggesting the world must swear off fossil fuels by the middle of the century to prevent the worst impacts of global warming.

“Clean coal is a deliberately misleading term,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, a senior analyst at Greenpeace’s air pollution unit. “In the context of cutting greenhouse-gas emissions, there are two kinds of coal: far too polluting, and far too expensive.”

The moniker “clean coal” was most famously used by U.S. President Donald Trump in his State of the Union address and actually refers to a range of technologies. Some remove impurities from different grades of the fuel to make it burn more quickly, delivering greater power. Others scrub sulfur dioxide, which causes acid rain, and nitrous oxide, which harms the Earth’s ozone layer and worsens respiratory conditions such as asthma.

Trump made reviving what he calls “beautiful clean coal” a cornerstone of his legislative agenda, vowing to bring back jobs to the ailing industry. His administration has also argued that keeping coal plants provides a cheap and secure energy source that can’t be matched by wind, solar or natural gas.

The most promising systems essentially burn coal at super-high temperatures more quickly than conventional plants, squeezing more energy out of each ton of fuel. Their costs are about 40 percent higher than a regular plant, and their carbon dioxide emissions are 25 percent to 35 percent lower, according to the World Coal Association. On pollution, they can even rival natural gas, the cleanest fossil fuel.

“The best coal-fired plants are now producing emissions of NOx, SO2 and particulates that are actually lower than gas plants, which is certainly saying something,” said Ian Barnes, principal associate at the IEA’s Clean Coal Center. “For poorer countries like Bangladesh, the availability of affordable power will help to lift millions of people out of poverty.”

For the coal industry, this technology represents a better way to slow the growth in emissions while ensuring greater access to electricity.

The World Coal Association estimates it would cost $31 billion to upgrade 400 gigawatts of coal stations to use the best technologies. That’s a fraction of the $2.4 trillion-a-year investment in clean energy that’s needed to avoid a dangerous warming of the planet, according to a panel of scientists convened by the United Nations.

The most efficient plants operating now, like EnBW’s so-called RDK8 unit in Karlsruhe, are dubbed “ultra-supercritical,” or USC for short.

The name comes from the method of heating water to make steam, operating at a temperature of 600 degrees Celsius (1,100 Fahrenheit)—a third hotter than an oven set to the self-clean cycle. Under intense heat and pressure, water enters a “supercritical” phase where it’s neither a liquid nor a gas but has properties of both. That steam hits the 50-ton power-generation turbine at Karlsruhe with the force of a bullet, rotating it 50 times a second.

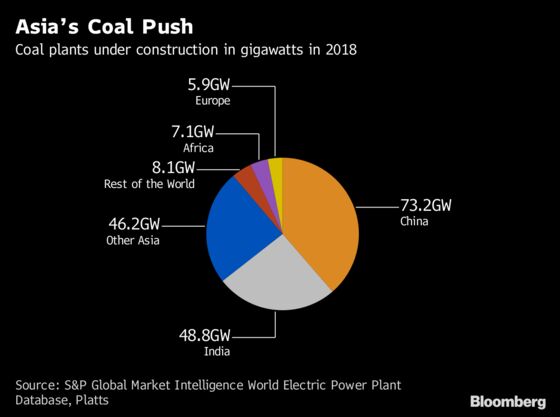

Manufacturers including GE, IHI Corp. and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. in Japan, Siemens AG in Germany and Doosan Corp. in South Korea are promoting these USC plants as a way to make coal cleaner for places that need cheap energy. They’re vying for orders in Asia, especially China, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Indonesia, which have fewer alternatives than rich industrial countries.

“If we stop coal-power plants all of a sudden, that will leave the world in disarray,” said Hiroshi Ide, executive officer and vice president of resources, energy and environment at IHI in Tokyo. “The dangerous thing is if customers choose coal power and pick the cheap and inefficient equipment, which emits a lot of carbon dioxide.”

Environmental lobbyists are the most obvious threat to these ambitions. Groups like the Sierra Club, backed by Michael Bloomberg, who owns Bloomberg LP and Bloomberg News, along with the Natural Resources Defense Council have focused attention on the harm done by coal pollution. They note that even the best coal plants contaminate groundwater and put mercury and dust into the air—in addition to their greenhouse-gas footprint.

“There is an honest concern among many in government around the world to modernize their economies and remedy energy poverty,” said David Schlissel, director of resource and planning at the Institute for Economics and Financial Analysis, an environment-focused research group based in Cleveland, Ohio. “For more than a century, burning coal was an accepted and economical way to do this. This is no longer the case.”

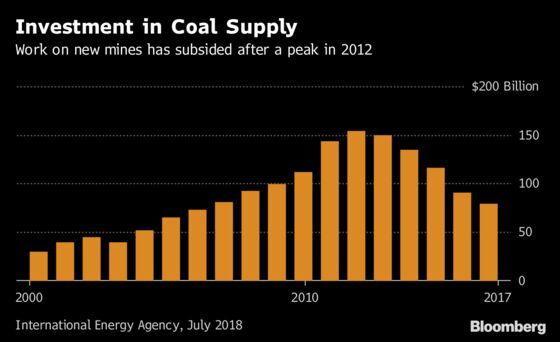

The clean-coal industry’s bigger hurdle may be finance, which is drying up quickly in Europe and the U.S., mainly because the projects are so costly and complex.

In the U.S., the only large clean-coal plant is NRG Energy Inc.’s W.A. Parish Unit 8 in Texas, which has a carbon-capture system added to it using Mitsubishi technology. It captures 90 percent of the CO2 in the processed flue gas and also has systems that reduce emissions of sulfur, mercury, nitrogen oxide and particulates. Southern Co. abandoned the clean-coal section of its $7.5 billion Kemper plant in Mississippi after cost overruns and problems building structures that could withstand temperatures above 900 degrees.

At AES Corp., a utility based in Arlington, Virginia, that operates power plants of all kinds in 15 countries, Chief Executive Officer Andres Gluski has been winding down his company’s commitment to coal mainly because of cost. In the past year, he’s sold or closed 4.5 gigawatts of coal plants and built 3 gigawatts of renewable-energy capacity. A gigawatt is about as much as a single nuclear reactor produces.

“You need 20 years just to pay off the debt,” Gluski said. “Where do you think that makes sense? We don’t see any new coal in the U.S. That’s the bottom line.”

Even in Asia, where the IEA expects dozens of new coal plants to be built in the coming years, it’s becoming more difficult to get loans. Development banks are shifting more of their support to green-energy projects, backing the goals of governments to rein in pollution.

“There’s really no such thing as clean coal,” said Woochong Um, director-general of the sustainable development and climate-change department at the Asian Development Bank, which is based in Manila. “In the last five years, we haven’t found the type of coal project we would do.”

--With assistance from Chris Martin, Mark Chediak and Brian Parkin.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Reed Landberg at landberg@bloomberg.net, Amanda JordanTimothy Coulter "Tim"

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.