What’s Next for China Evergrande, Crushed by Debt

Here's what you must know about the China Evergrande Group and the crisis that it is going through.

(Bloomberg) -- One of China’s largest-ever debt restructurings is looming in 2022, with the Communist Party now in the driving seat, after China Evergrande Group, the world’s most indebted property developer, was formally declared to be in default. While the state’s intervention has quelled fears of a disorderly collapse that would jolt the world economy, investors who hold Evergrande bonds are wondering how much of their money they’ll see after the dust settles. Meanwhile, Evergrande is under pressure to deliver thousands of pre-sold housing projects -- and to pay its workers -- to avoid sparking social unrest.

1. How did we get here?

Evergrande, founded in 1996, grew through massive borrowing. Back in 2010, it sold the then biggest dollar bond among Chinese property developers, with a $750 million offering. The firm has since embraced a debt binge to fuel growth, rising to be the largest dollar debt borrower among peers and the fifth largest developer in China by contracted sales. It owns more than 1,300 projects in 280 cities, according to the company website. Following a liquidity scare in 2020, the company outlined a plan in early 2021 to cut its $100 billion debt pile roughly in half by mid-2023. Meantime, China’s housing market was slowing down amid regulatory curbs. Another liquidity scare sent Evergrande’s stock and bonds tumbling, and in early December, following a succession of payment failures, it missed a deadline to pay two dollar bond coupons within a grace period. On Dec. 6, Evergrande’s board announced the establishment of a “risk management committee” dominated by provincial officials.

2. Might the government still bail out Evergrande?

The prospect was long seen as unlikely and faded further on Dec. 9 when People’s Bank of China Governor Yi Gang said the company will be dealt with in a market-oriented way. A full bailout would tacitly condone the type of reckless borrowing that landed one-time high-flyers like Anbang Group Holdings Co. and HNA Group Co. in trouble as well. Ending moral hazard -- a tolerance in business for risky bets in the belief that the state will always bail you out -- also would make the financial system more resilient over the long run. On the other hand, allowing a big, interconnected company like Evergrande to collapse would reverberate across the financial system and also be felt by many millions of Chinese homeowners. The company is rushing to deliver thousands of housing projects, and was told by Chinese regulators to prioritize payments to migrant workers and suppliers. On a broader level, China plans to set up a financial stability fund and adopt measures to stabilize home prices, Premier Li Keqiang said in March, as part of continuing efforts to reduce systemic risks.

3. Who are the bondholders?

Some of the world’s biggest investment firms. Ashmore Group, BlackRock Inc., FIL Ltd., UBS Group AG and Allianz SE have all reported holding Evergrande debt, Bloomberg-compiled data show. They now face deep haircuts in a restructuring that could take years to resolve.

4. How much bargaining power do bondholders have?

Not much. Evergrande said in late December that the government-led, risk-management committee will actively engage with the company’s creditors. Some offshore noteholders see little use in pressing their case in Chinese courts, given the government’s heavy involvement in the overhaul. The fact that this is a cross-border restructuring with debt-issuing units listed in multiple jurisdictions creates another challenge for bondholders trying to get organized and show a united front. Still, some offshore creditors are already consulting with financial and legal advisers.

5. How bad are Evergrande’s finances?

Evergrande’s property sales plummeted in 2021 for the first time in at least a decade, down 39% from the previous year, with sales almost frozen since October. Meanwhile, it had some 1.97 trillion yuan ($309 billion) in liabilities as of June 30, the most among its peers in China. Almost half of that amount is bills to suppliers and other payables, while interest-bearing debt totaled 572 billion yuan, down 20% from the end of 2020. The company has reduced its net debt-to-equity ratio to below 100%, meeting one of the Chinese government’s “three red lines” -- metrics imposed to limit borrowing by real estate companies. It has $19.2 billion in offshore dollar bonds outstanding, the most among Chinese developers. Another risk is the firm’s guarantees on related-party debts, including private placement bonds with limited disclosure.

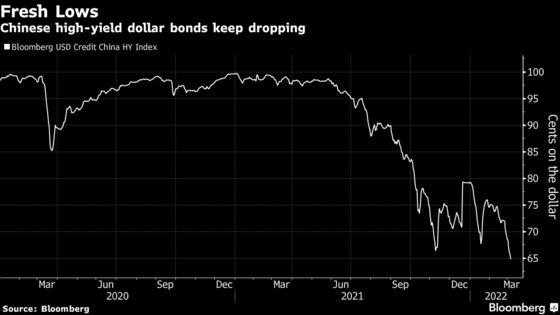

6. Are other developers in trouble?

Yes. The value of new homes sold by China’s hundred largest real estate companies fell annually for the first time since at least 2016 and declined further in December. Yields on Chinese junk bonds soared to a record high of about 25% in November after several developers either defaulted or signaled trouble.

- Kaisa Group Holdings Ltd., the third-largest issuer of dollar notes among Chinese developers, has $11.6 billion outstanding, including a $400 million bond it defaulted on in December.

- Fantasia Holdings Group Co. in early October defaulted on a $205.7 million bond, and

- Sinic Holdings Group Co. said days later it didn’t expect to repay a $250 million note.

- Modern Land (China) Co. defaulted on $250 million of a green bond in October and had since received creditors demand for early debt repyaments on its other obligations

- Shimao Group Holdings, once deemed a safer firm, lost all investment grade ratings in December and defaulted on onshore loan payments.

This year’s defaults on offshore bonds from Chinese borrowers set an annual record, with the property sector making up about one-third of those missing payments, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. China’s private-sector developers are selling the fewest bonds domestically in nearly five years, adding to the risk of additional defaults. The companies’ yuan bond issuance dropped to a combined 7.72 billion yuan in October and November, the smallest two-month total since January 2017. At least four developers are seeking investor permission to delay payment, while others are selling assets at a discount to raise funds.

7. Is Evergrande well-connected?

When President Xi Jinping marked the centenary of the Communist Party’s founding with a speech proclaiming his nation’s unstoppable rise, there, overlooking the festivities in Tiananmen Square, was Evergrande founder Hui Ka Yan. Born into poverty, the son of a wood cutter, Hui has been a party member for 35 years and has invested in areas endorsed by the top leadership, such as electric vehicles and traditional Chinese medicine. He’s a prominent philanthropist, although his net worth has taken a beating, and Evergrande’s purchase of local soccer team Guangzhou F.C. indicates he shares Xi’s passion for the sport. In the end, those political ties were not enough to avert a default. Hui was said to have requested personal leave from the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in March as Evergrande tries to defuse operational risks.

The Reference Shelf

- Additional QuickTakes on how defaults are reshaping China’s credit market, what China’s three red lines for property firms are, and how its financial market opening is going.

- A timeline of the Evergrande crisis, and an episode of Bloomberg Quicktake’s The Breakdown.

- Bloomberg Opinion doubts that Evergrande is another Lehman Brothers.

- Bloomberg Intelligence assesses the stakes.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.